4 Chapter 4: Survey Research

CASE STUDY: National Crime Victimization Survey

Criminal Victimization in the United States1

How many violent and property crime victimizations occurred in the United States in 2010?

The results of the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) are provided on an annual basis by the U.S. Census Bureau and serve as an alternative to the Uniform Crime Reports. The NCVS collects information on the violent crimes of rape or sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault, and the property crimes of household burglary, motor vehicle theft, and theft. The results are derived from a nationally representative sample of U.S. households selected through a stratified, multistage cluster sampling process (see Chapter 3). The survey results are based on data gathered from residents living throughout the United States, including persons living in group quarters, such as dormitories, rooming houses, and religious group dwellings. Armed Forces personnel living in military barracks and institutionalized persons, such as prison inmates, are not included in the survey.

Each housing unit selected for the NCVS remains in the sample for 3 years, with each of the seven interviews taking place at 6-month intervals. An NCVS interviewer’s first contact with a household selected for the survey is in person and the survey is completed through a face-to-face interview. The interviewer may conduct subsequent interviews by telephone. To elicit more accurate reporting of incidents, the NCVS uses a self-report method that includes a direct interview with each person 12 years or older in the household. In 2010, 40,974 households and 73,283 individuals age 12 and older were interviewed for the NCVS. Each household was interviewed twice during the year. The response rate was 92.3% of households and 87.5% of eligible individuals.

The NCVS has been collecting data on personal and household victimization since 1973. The data include type of crime, month, time and location of the crime, relationship between victim and offender, characteristics of the offender, self-protective actions taken by the victim during the incident and results of those actions, consequences of the victimization, type of property lost, whether the crime was reported to the police and reasons for reporting or not reporting, and offender use of weapons, drugs, and alcohol. Basic demographic information such as age, race, gender, and income is also collected to enable analysis of victimization by various subpopulations.

During 2010, U.S. residents age 12 or older experienced an estimated 18.7 million violent and property crime victimizations, down from 20.1 million in 2009 and 24.2 million in 2001. The criminal victimizations in 2010 included an estimated 3.8 million violent victimizations and 14.8 million property victimizations. Violent and serious violent victimizations (includes rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault) declined by nearly 34% between 2001 and 2010.

From 2001 to 2010, weapon violence (26% to 22%) and stranger-perpetrated violence (44% to 39%) declined. Between 2001 and 2010, about 6% to 9% of all violent victimizations were committed with firearms. This percentage has remained stable since 2004. The percentage of victims of violent crimes who suffered an injury during the victimization increased from 24% in 2008 to 29% in 2010. About 50% of all violent victimizations and nearly 40% of property crimes were reported to the police in 2010. These percentages have remained stable over the past 10 years. Males (15.7 per 1,000 population) and females (14.2 per 1,000 population) had similar rates of violent victimization during 2010.

Limitations with the Study Procedure

While rape or sexual assault significantly increased from 2009 to 2010, you should be cautious in interpreting this change because the estimates of rape/sexual assault are based on a small number of cases reported to the interviewers. Small changes in the number of victimizations can result in large year-to-year percentage changes. For instance, the 2010 estimate of rape or sexual assault is based on 57 reported cases compared to 36 reported cases in 2009. This represents an increase of 21 actual cases but also represents a 49.6% increase in the national estimate of rape or sexual assault from 2009 to 2010. The measurement of rape or sexual assault represents one of the most serious challenges in the field of victimization research. Rape and sexual assault remain sensitive subjects that are difficult to ask about in the survey context.

Any time national estimates are derived from a sample rather than the entire population, as is the case with the NCVS, because of sampling error it is important to be cautious when drawing conclusions about the size of one population estimate in comparison to another (e.g., does aggravated assault occur more frequently than robbery?) or about whether population estimates are changing over time (e.g., did robbery increase or decrease in the past year?). Although one figure may be larger than another, the NCVS estimates are based on responses from a sample of the population. Therefore, each estimate has some degree of sampling error. The sampling error of a population estimate depends on several factors, including the amount of variation in the responses, the size and representativeness of the sample, and the size of the subgroup for which the estimate is computed, as illustrated in the rape or sexual assault example previously discussed.

In addition to sampling error, the NCVS results are subject to non-sampling error. While substantial care is taken in the NCVS to reduce the sources of non-sampling error throughout all the survey operations, an unknown amount of non-sampling error still remains. A major source of non-sampling error includes the inability of the respondents to recall in detail the crimes that occurred during the six months prior to the interview. The NCVS uses a 6-month reference period. Respondents are asked to report victimization experiences occurring in the last 6 months. Generally, respondents are able to recall more accurately an event that occurred within 3 months of the interview rather than one that occurred within 6 months. Research indicates that assault is recalled with the least accuracy of any crime measured by the NCVS. This may be related to the tendency of victims to not report crimes committed by offenders who are not strangers, especially if they are relatives. Recall problems may result in an understatement of the actual rate of assault.

However, a shorter reference period would require more field interviews per year, increasing the data collection costs significantly. These increased costs would have to be balanced by cost reductions elsewhere (sample size is often considered). Reducing sample size however, reduces the precision of estimates of relatively rare crimes such as rape or sexual assault. In light of these trade-offs of cost and precision, a reference period of 6 months is used for the NCVS.

Other sources of non-sampling error can result from other types of response mistakes, including errors in reporting incidents as crimes, misclassification of crimes, systematic data errors introduced by the interviewer, and errors made in coding and processing the data.

The NCVS is one of the two national sources of crime data in the United States. The NCVS is generally viewed as a more reliable and valid measure of crime than the Uniform Crime Reports. The data from the NCVS survey are particularly useful for calculating crime rates, both aggregated and disaggregated, and for determining changes in crime rates from year to year. In addition, the NCVS is the primary source of information on the characteristics of criminal victimization and on the number and types of crimes not reported to law enforcement authorities. It provides the largest national forum for victims to describe the impact of crime and the characteristics of violent offenders.

In This Chapter You Will Learn

Why nonresponse is a major source of survey error and how nonresponse impacts survey results

The four main mechanisms for assessing validity as well as how to increase the validity of survey questions and responses

How to assess the reliability of survey questions and responses as well as ways to increase reliability

The methods in which surveys are distributed and the strengths and weaknesses of each

Introduction

Survey research involves the collection of information from individuals through their responses to questions, and represents one of the most widely used research tools in crime and criminal justice studies. Surveys are one of the most common ways to obtain information about attitudes and behaviors and involve collecting information from people via self-administered surveys, telephone interviews, face-to-face interviews, and more recently Internet and e-mail–based surveys.

In survey research, the main way of collecting information is by asking people questions. Their answers constitute the data to be analyzed. For example, the U.S. Census is a self-administered survey where individuals receive surveys in the mail and are asked to fill them out and send them back to the U.S. Census Bureau. In addition to the counting of people, the U.S. Census collects data about the race, age, household composition, education, type of housing, and many other characteristics of the people counted. As presented in the introductory case study, the NCVS is another example of a large-scale survey where data is collected via face-to-face and telephone interviews.

Most people are familiar with surveys, especially those that involve the measurement of public opinion for newspaper and magazine articles, the measurement of political perceptions and opinions involving politicians, and marketing research designed to understand consumer preferences and interests. In fact, we are inundated with surveys in our daily lives. From the restaurant that offers you a free appetizer on a future visit for completing a telephone survey about your experience, to the call center that wants your feedback on the performance of the customer service representative at the conclusion of your phone call, to solicitations to complete online surveys regarding your website experience, to the evaluation of your professor at the end of the semester, we don’t have to look far for an example of a survey in our daily lives.

The same is true for research in criminology and criminal justice. Surveys are frequently the data collection method of choice to answer research questions. For example, if we want to know whether the police officers in our local police department prefer to work 8-, 10-, or 12-hour shifts, we can survey them to address this issue. If we want to determine the level of fear of crime on a college campus, we can survey students, faculty, staff, and visitors to gauge their level of fear of crime. If we want to know if the public agrees with recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions, we can survey residents and ask them their opinion. If we want to understand how correctional officers view their roles and interactions with inmates, we can survey the officers regarding the topic. If we want to identify the extent, causes, and consequences of bullying, we can survey students to better understand bullying. Overall, surveys can be used to answer a wide range of research questions involving crime and the operation of the criminal justice system.

Three characteristics of surveys make them a preferable source of data collection in comparison to other sources.2 First, probability sampling is typically used in surveys, which enables the research consumer to have confidence that the sample is not a biased one and is a reflection of the larger population. Data from research studies using a probability sample are definitely preferred over data from a non-probability sample, such as those who attend a college class or happen to be convenient to survey. Second, standardized measurement (i.e., each respondent is asked the same questions in the same manner) ensures that comparable information is obtained about everyone who responds to the survey. Standardized measurement produces meaningful statistics and comparisons of respondents (e.g., how are juveniles who are chronically truant different from juveniles who are not?). Third, the development of a survey ensures that all the data needed for a given analysis are available. For example, you may find in your literature that parental supervision is an important factor that distinguishes truants from nontruants. Since you are creating the survey, you can be sure to ask questions about the respondent’s level of parental supervision so the relationship between truancy and parental supervision can be addressed in your study.

Survey Components

Surveys bring together sampling, question design, and methods of survey distribution. It is important to note that each of these activities has many applications outside of surveys, but their presence is essential to quality surveys. For consumers of research, it is important to understand how the details of each component of a survey can affect its precision, consistency, and accuracy (i.e., its reliability and validity). How the sample is selected, which questions are asked, and the procedures used to collect the answers all impact the quality of the survey and its results.3

Sampling With the U.S. Census as an exception, survey information is typically collected from a sample of the population, rather than from every member of the population. The ability to select a sample that is representative of the whole population was a significant development that made surveys a useful research tool. The keys to good sampling are finding a way to give all (or nearly all) members of the population the same (or a known) chance of being selected and using probability sampling methods for choosing the sample.4

Every survey involves a number of decisions that have the potential to enhance or detract from the accuracy of the survey results. With respect to sampling, critical issues include the following: the choice of whether or not to use a probability sample, the size of the sample, the sampling technique utilized, and the rate of response (the percentage of those sampled who respond to the survey). Since sampling was covered in detail in Chapter 3, it will not be revisited in this chapter. At this point, realize that probability sampling techniques are typically used in surveys. Therefore, the material covered in Chapter 3 is applicable to survey development and distribution. This chapter will discuss the response rate for surveys since it directly applies to surveys and was not covered in Chapter 3.

Survey Question Design In surveys, the questions measure the concepts and variables under study. Survey question design is a critical element of survey research. Sticking with the theme of this book regarding the development of educated consumers of research, the focus on question design in this chapter will not be on how to write survey questions but on strategies for evaluating the quality of the questions. Survey researchers evaluate questions to find out if they are well understood by the respondents and if the answers are meaningful. In other words, the reliability and validity of the survey questions must be assessed in determining the quality of the survey. The researcher must decide the extent to which previous literature regarding the reliability and validity of questions will be drawn upon in the development of the survey as well as the process for question evaluation.

Methods of Survey Distribution Surveys can be distributed through several means, including face-to-face or telephone interviews or through self-administered means via the mail or Internet. Some surveys have respondents answer self-administered questions while others use an interviewer to ask questions and record answers. When interviewers are used, it is important to avoid having them influence the answers given by the respondents. The decision about which mode of data collection to use has important cost implications and affects the quality of the data that will be collected.5

The three components of survey development (i.e., sampling, question design, and methods of distribution) are interrelated because the quality of the survey data will not be better than the most error-prone feature of the survey design. A large sample size will not make up for a low rate of response. Similarly, a high response rate will not compensate for unreliable and invalid survey questions. Survey researchers must focus on each component of the survey, including sampling, question design, and method of distribution, because weaknesses in one area cannot be rectified by the strengths of another area.

Since sampling has already been covered in Chapter 3, this chapter discusses question design and methods of survey distribution. A concentrated effort is made to discuss the realities and the practical problems with the decisions made by survey researchers. The goal is to provide a comprehensive overview of the sources of error in surveys and the range of methodological issues that arise when using surveys. Although survey research is a common way to solicit information from a wide variety of individuals, it is not without its limitations, which will be discussed throughout this chapter. We begin our discussion with an overview of the sources of error in survey research.

Issues in Survey Development: Nonresponse and Survey Design

Sampling error, as discussed in Chapter 3, occurs because the sample drawn from a population will not exactly match the population. For example, survey results from a sample of citizens on attitudes toward the use of the death penalty will not be identical to the overall survey results if an entire state population of citizens was surveyed. As discussed in Chapter 3, the difference in survey results between a sample and a population is called sampling error. Researchers expect there to be a difference between the sample results and the results from an entire population, even when the sample is representative of the population. They just try to minimize the error as much as possible.

When a sample is drawn, it is inevitable that the sample will differ from the population from which it was drawn. The way the sample is drawn (e.g., probability vs. non-probability sampling) can affect how closely the sample is likely to mirror the characteristics of the population. Regardless of the sophistication of the sampling strategy, by chance, the sample will differ slightly from what it would look like if it was an exact mirror image of the population. One of the goals of survey research is to minimize the random, by chance differences between the sample and the population.

Nonresponse

Nonresponse is a major source of survey error. There are three categories of nonrespondents (i.e., those selected to be in a sample who do not actually respond to the survey)6:

1. Those who did not receive the survey, thereby not giving them a chance to respond to the survey. For example, this includes mailed surveys that are undeliverable due to bad addresses and telephone surveys that fail to call when the potential respondent is available to answer the phone.

2. Those who receive the survey but refuse to complete it. For example, this includes potential respondents who refuse to participate in the NCVS even though their household has been selected for participation. In 2010, 7.7% of the sampled households refused to participate in the survey.7

3. Those asked to participate in the survey but are unable to perform the task required of them. This includes people who are too ill to be interviewed, who have language barriers, or whose reading and writing skills preclude them from completing a self-administered survey.

Failure to collect survey data from a high percentage of those selected to be in a sample is a major source of survey error.8 When it comes to surveys, the quality of the results not only depends on how well the sample is a close approximation of the population but also how well those who respond to the survey reflect the total population. The method of distribution that a researcher decides to use can have a major influence on the response rate and the extent to which nonrespondents introduce bias into the results. As discussed later in this chapter, some methods of distribution (e.g., face-to-face interviews) have higher response rates than other distribution methods (e.g., mailed surveys). Overall, a low response rate will bias the sample, which means that the nonresponse makes the respondents systematically different from the population from which they were drawn, thereby producing biased results. For example, let’s say we surveyed 100 physicians on the effects of energy drinks on general health, and 50 returned the survey, for a response rate of 50%. The question we should consider is, “How do the 50% who did not respond differ from the 50% who did?” In this circumstance, if we had the other 50% of the responses, they might totally change the results of the study.

Calculating Response Rates In assessing the quality of a research project that used a survey to collect data, the response rate is a basic parameter for evaluating a project. Simply, the response rate is the number of people who respond to the survey divided by the number of people sampled. The denominator includes all people in the sample who were selected as a potential survey respondent but did not respond for whatever reason. This includes the three categories of nonrespondents previously listed, including those who do not receive the survey, those who receive the survey but refuse to participate, and those who are asked to participate in the survey but are unable to perform the task required of them.

Since the response rate is a simple way to assess the quality of a study involving a survey, researchers want to demonstrate a high response rate. To this end, some researchers do not include some of the categories of nonrespondents in the calculation of the response rate, which artificially inflates the response rate for the study. Most commonly, the category of nonrespondents that are excluded from the response rate calculation are those who did not receive the survey.

For example, let’s say that a sample of 1,000 college students has been selected for a survey, designed to be completed via telephone interviews, on criminal victimization on campus. In this fictitious study, 500 students completed the survey, 100 students refused to complete the survey and hung up on the interviewer, while another 400 never answered their phone despite numerous calls. What is the response rate? Based on the discussion above, the response rate is 50%. The response rate is the number of people who complete the survey (i.e., 500) divided by the number of people sampled (i.e., 1,000). However, some researchers will exclude the 400 potential respondents who were in the sample but never answered their phone despite repeated attempts. With this exclusion, the response rate is now 83.3%, which is much higher, and therefore better, because the researcher has only included those who completed the survey and those who refused to do so in the response rate (i.e., 500/600).

As an educated consumer of research, you need to be cautious when interpreting response rates. It is important to specifically know how the reported response rate was calculated. As illustrated in the example, differences in the way response rates are calculated can make comparisons across studies difficult. Instead of reporting a response rate, some researchers will report a “completion rate,” which excludes those who did not receive the survey from the calculation. In our above example, the completion rate is 83.3% because the 400 students who never answered the phone are excluded in the calculation. The completion rate will always be higher than the response rate as outlined above, which includes selected but uncontacted individuals in the denominator. Although a response rate seems simple to calculate, be sure to remember that it is important to understand how the response rate was calculated before you decide if the response rate is high.

The Impact of Nonresponse You may now be wondering what is an acceptable response rate. Babbie9 has suggested that a 50% response rate is adequate, 60% is good, and 70% is very good. Besides focusing on the numeric value of the response rate and how it fits with Babbie’s categorization, it is more important to determine if those who did respond are a representative cross section of the sampled group than it is to have a high response rate. In other words, it is critical for the survey researcher to assess if there are significant differences between the respondents and the sample.

In addition, ideally, a researcher will have meaningful information on those who did not respond. Demographic variables such as education, race, ethnicity, gender, age, and income may be helpful in assessing differences between respondents and nonrespondents. An assessment could show that those who did respond to the survey were quite similar in terms of education, race, ethnicity, gender, age, and income to those who did not respond. If the respondents and nonrespondents are quite similar, a researcher could legitimately analyze the results of a survey even if the response rate was extremely low (e.g., 10%). Basically, the effect of nonresponse on survey results depends on the percentage not responding and the extent to which those not responding are biased (i.e., systematically different from the population). Again, the issue isn’t specifically about the response rate, but more critically about whether the respondents and nonrespondents are similar or different on key characteristics that are related to the research questions.

Another issue that needs to be considered in determining the adequacy of the response rate is the population studied. You would expect a higher response rate from a survey of students in the Introduction to Criminal Justice course at your university than from a citizen survey in the same community, even though the topic may be the same. The students probably have a preexisting relationship with the researcher, which, coupled with the use of a group-administered survey (discussed later in this chapter), will lead to a higher response rate in comparison to a survey that is mailed to community residents. In addition, individuals that have an interest in the survey topic are more likely to respond to a survey than those who are less interested. Therefore, you can expect a higher response rate from a survey of police chiefs in California regarding the role of municipal police departments in fighting terrorism than from a survey of California residents on the same topic. Therefore, the adequacy of a response rate is more complex than merely looking at the number and determining how it measures up to Babbie’s stated standards.

An example of significant bias from low response and poor sampling where the respondents were significantly different from the population is the classic Literary Digest presidential poll in 1936. The survey, which was administered via mail, predicted a victory for Alf Landon in an election that Franklin Roosevelt won by a huge margin. The sample of addresses for the mailed survey was selected from telephone books. At the time, not everyone had a telephone so most voters were not listed in the telephone book. In addition, Republicans (those in Landon’s party) were much more likely to have telephones in 1936. Furthermore, only a minority of those asked to return questionnaires did so, which also led to the inaccurate survey results.

Overall, nonresponse is a problematic source of survey error. As the response rate decreases, it becomes more likely that the nonrespondents will differ from the survey respondents. When there are significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents, each group represents biased subgroups of the total population. Bias means that in some systematic way the individuals responding to a survey are different from the overall population. Therefore, the results based on the survey respondents are not reflective of the overall population.

Although we can calculate a response rate, we usually do not know for sure the impact of nonresponse on the survey results. Perhaps the strongest argument for efforts to increase response rates is credibility.14 When response rates are high, there is only a small potential for error due to nonresponse to have a significant impact on the survey results. When response rates are low, there is great potential for error due to nonresponse to have a significant impact on the survey results. Finally, a low response rate also provides critics of the survey results an easy, intuitive basis on which to say the data are not credible.

WHAT RESEARCH SHOWS: IMPACTING CRIMINAL JUSTICE OPERATIONS

What Causes Inmates to Riot?10

Early research into the causes of prison riots focused primarily upon the deprivations that are part of the prison environment. Gresham Sykes11 provided one of the first analyses of prison riots when he explored the causes of two riots that took place at the New Jersey State Prison in the spring of 1952. Sykes attributed the riots to changes in the inmate social system that had stripped the inmates of their control. Based on his observations, Sykes believed that the transfer of power from the inmate social system to prison staff exaggerated the deprivations experienced by inmates and contributed to the riots. His insights, however, failed to provide a complete understanding of why inmates rioted. Overcrowding, poor living conditions, lack of programming, guard brutality, poor administration, and a concentration of violence-prone inmates have all been cited as contributing factors to riots despite the fact that these conditions also exist in prisons where no riots have ever taken place. Further, Sykes’ explanations of prison riots were based on a case study (see Chapter 6) from a single prison facility where a riots had occurred.

In an effort to formulate a more comprehensive explanation for why inmates riot, Richard Wilsnack examined data from 48 state prisons. Included in his sample were prisons that had experienced a riot, some other type of collective inmate violence (e.g., work stoppage and hunger strikes), as well as prisons with no reported collective violence. He was the first to conduct a large-scale quantitative study of collective inmate violence. He created a 160-question survey that was mailed to 51 correctional institutions, including the largest state prison institution for each state and the District of Columbia. All of the prisons housed adult males convicted of felony crimes and were medium or maximum security facilities. Institutions were selected to be representative of the types of prisons where riots were most likely to occur. Only three states—Alabama, Kansas, and Mississippi—failed to respond to the survey, for a response rate of 94%. To improve the reliability of responses, questions were constructed in such a way that respondents had to provide only simple replies.

Twelve of the prisons surveyed reported a riot during the study period. The study identified several contributing factors to the riots. First, an analysis of prison conditions revealed that inmate deprivation, disorganization, and conflict existed in prisons where riots had taken place. Three-fourths of the prisons reporting a riot had experienced an increase in inmate assault and/or had at least one occurrence of an inmate assault on a guard. Second, administrative instability and conflict were related to prison riots. Three-fourths of the prisons reporting a riot had experienced major administrative changes (i.e., turnover or extended absences) and conflict among staff members. While a shortage of correctional staff was not related to the occurrence of a riot, low salaries and high staff turnover were found to be associated. Third, external pressures existed in prisons where riots had taken place. Wilsnack found that pressure and publicity from outside of the prison were also related to the occurrence of a riot. All of the riots had taken place in institutions where legislators and concerned citizens had tried to influence prison operations. In addition, 80% of these institutions had received some type of media coverage prior to the riot. Overall, riots were more likely to occur in maximum security prisons with overcrowding and unoccupied inmates. Furthermore, riots were more likely to occur in facilities where inmates of different ages, convictions, and prior records were all housed together. Wilsnack’s findings did not support Sykes’ contention that riots occurred as a result of a disruption of the inmate social structure.

Wilsnack’s quantitative study of inmate collective violence enhanced our understanding of prison riots and other forms of collective prison disturbances. Despite the difficulties in researching prison riots, our understanding of the causes has grown significantly over the past several decades. Researchers have uncovered many of the conditions associated with prison riots and several theories have been developed to explain their occurrence. Prison administrators today are better equipped to respond to prison riots with emergency response teams. These teams consist of officers trained in hostage negotiation and disturbance control.

This body of research has also helped prison administrators develop preventative measures to reduce the likelihood of riots. Regular security audits, consistent enforcement of rules and procedures, maintaining effective communication between inmates, staff, and administrators, providing inmates with structured activities and appropriate programs, and using inmate classification systems are all important strategies for preventing the occurrence of riots.12 The number of prison riots has significantly declined since the 1970s, despite the large increases in the number of inmates. According to Useem and Piehl,13 this trend can be attributed to more effective prison management.

Survey Question Design

Designing a good survey instrument involves selecting survey questions that are needed to answer your research questions. As discussed in Chapter 1, one of the initial steps in any research project is to develop a research question or questions. The same is true for survey research. Since responses to the survey questions are the data collected in surveys, the survey responses are used to answer your research questions. Therefore, it is critical that questions included in the survey are able to answer your research question. For example, if your research question is, “Is there a relationship between parental supervision and chronic truancy?” you need to ask survey questions that can measure the variables identified in the research question: parental supervision and chronic truancy. Designing a question for a survey instrument is designing a measure.

Besides the recognition that the survey questions must be able to be used to answer the research questions, how do researchers know what to ask on a survey? When building a questionnaire, a survey researcher has two sources for survey questions. First, the researcher can include survey questions that have been used in other surveys. When another researcher has already designed a quality set of questions to measure a variable in your research question, it is recommended that you use the items from the preexisting survey, with a few caveats. First, the existing survey questions must be reliable and valid, which will be discussed in the next section. For now, this basically means that the survey questions must be a quality measurement of the variable. For example, if you are creating a survey to address criminal victimization on your campus, a great starting point for developing the survey questions is to use the NCVS, covered in the chapter opening case study, as a template for your survey questions. You can certainly modify the questions to meet your specific needs, but the NCVS is a high-quality measurement of criminal victimization and so it is a reasonable place to start when creating the survey questions. Second, you need to provide appropriate citation to the original developer of the survey questions in the research manuscript. For example, Rosenberg15 developed a measure of self-esteem that is the most often used measure of self-esteem in survey research. In order to use the 10-question measure of self-esteem or a modified version, the researcher must provide appropriate citation to its original source.

A good source for prior surveys on a wide range of topics is the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan.16 Your university probably belongs to the ICPSR. ICPSR is a website depository where major social and political survey files are archived. If your university belongs to ICPSR, you can get codebooks for any study on file at ICPSR. The codebooks include the actual survey questions asked and the response formats used. The studies archived at the ICPSR cover a wide range of criminal justice and criminology topics, so it is a good starting place if you are ever tasked with developing a survey.

Second, when building a questionnaire, a researcher can include items that she has personally constructed. This is the favored option when a satisfactory measure of the variable does not already exist or the variables in the research question are unique. Despite the discussion above, do not think that every good question about a topic has already been asked. And do not think that the questions perfectly suiting your purposes have already been formulated. Finally, it is certainly reasonable to use both options (i.e., prior surveys and personally constructed items) when constructing a survey. As you are reading and evaluating survey research, the researcher should inform you about the source of the questions: whether based upon prior surveys or if questions were developed by the researcher.

RESEARCH IN THE NEWS

Want a Job? Check the Spelling on Your Facebook Profile.17

When it comes to looking for jobs, you better put your best Facebook forward. Recruiters are looking, and frankly, they are not impressed with your poor grammar or posts about your latest unforgettable exploits, according to a new survey. The survey was conducted by social recruiting platform Jobvite. The company surveyed more than 1,000 human resources and recruitment professionals on their social recruiting activities and intentions with over 800 responding to the survey. Respondents answered questions using an online survey tool.

In addition to checking your résumé, nearly 3 out of 4 hiring managers and recruiters check candidates’ social profiles, even if they are not provided on your résumé, with some of the content garnering negative reactions. Content that recruiters especially frown on includes references to using illegal drugs (78% negative) and posts of a sexual nature (67% negative). Profanity in posts and tweets garnered a 61 % negative reaction, and almost half (47%) reacted negatively to posts about alcohol consumption. Worse than drinking, grammar or spelling mistakes on social profiles saw a 54% negative reaction from respondents. However, recruiters and hiring managers tend to be neutral in their reactions to political opinions (62% neutral) and religious posts (53% neutral).

Survey Questions and Answers: The Presence of Error

In order to conceptualize the error associated with answers to survey questions, it important to address what a survey is designed to measure. At its most basic, surveys try to measure two items: objective facts and subjective states. Objective facts include the number of times a person has been arrested, whether or not a person has used marijuana in the past week, and whether or not a person has been the victim of theft in the past 6 months. Subjective states include a person’s level of attachment to his parents and a person’s viewpoint on the primary purpose of prisons.

As will be discussed in the next section, the way we assess the answers to a survey question is to measure how well they correspond to the truth. If you are asking survey respondents about objective facts (e.g., how many times have you been arrested?), you can obtain independent information (e.g., criminal history information from a statewide database) against which to evaluate the answers to the survey question. Unfortunately, there is no objective way to verify or evaluate a person’s report about a subjective state (e.g., viewpoint on the primary purpose of prisons). There is no way to independently assess whether the person is telling the truth, which can cause error in the survey results.

A defining characteristic of survey research is that answers to the survey questions are used as the measurements of the concepts and variables in the study. The extent to which those answers are good measures of the concepts and variables is obviously a critical dimension of the quality of survey results. The extent to which the answers are not good measures creates survey error. Survey error comes from several areas, including misunderstanding the question, not having the information needed to answer, and distorting answers in order to look good, to name a few.18 For example, respondents typically underreport how much alcohol they drink and overstate their income. Survey results of alcohol consumption and income are likely to be biased (i.e., systematically different from the true scores). The issue is that to the extent that answers are impacted by factors other than the facts on which the answer should be based, there is error in the answer.19 The next section discusses the quality of the survey measurement and related error by discussing reliability and validity.

Survey Measurement Quality: Validity and Reliability

Assessing the quality (i.e., accuracy and consistency) of a survey measurement is a critical part of the research process. A survey researcher can spend days developing what he views as an excellent survey, but if the survey questions and responses are not accurate and consistent, the results of the study are questionable. Accurate and consistent survey questions and responses are essential to getting accurate results and making conclusions that reflect the true reality of the topic being studied. Specifically, the two key components of survey quality are reliability and validity. In order to be a high-quality measurement, survey questions and responses must be both reliable and valid. Reliability is necessary for quality measurement, but not sufficient. A quality measure must also be valid. Similarly, just because a measure is valid doesn’t necessarily mean it is reliable, and validity means little if the measure used is not reliable.

Validity addresses the accuracy of the measurement and refers to the extent to which researchers measure what they planned to measure. Validity refers to the accuracy and trustworthiness of survey instruments, data, and findings. The question asked when assessing validity is: “Are the survey questions measuring what they are intended to measure?”

Reliability addresses the consistency of a measurement and refers to whether or not you get the same answer if you use an instrument to measure something more than once. For example, if a police radar gun is used to measure the speed of two vehicles going the same speed and the same results are obtained, then the radar gun is reliable. Similarly, if a breathalyzer is administered to two individuals with the same blood alcohol level and the breathalyzer gets the same results each time, then the breathalyzer is reliable. In these cases, the radar gun is a reliable measure of the speed of automobiles, and the breathalyzer is a reliable measure of blood alcohol content (i.e., level of intoxication).

As previously discussed, surveys generally assess two different types of information: objective facts and subjective states. Generally, it is easier to accurately and consistently measure objective facts than subjective states. For example, it is easier to accurately and consistently measure a survey respondent’s gender, race, ethnicity, and education level (i.e., objective facts) than it is to measure a survey respondent’s opinion (i.e., subjective state) regarding the level and quality of police service provided to the community. The extent to which a survey is unreliable and invalid creates measurement error, which is a persistent problem in criminal justice and criminology research. One of the major sources of error in research studies is poor quality of the measurements.

Both validity and reliability must be present for high-quality research results. This section will address ways to measure and increase the validity and reliability of a measurement. It is important to note that validity and reliability do not just apply to survey research but to measurement completed in all research designs, including experimental designs (Chapter 5), field research (Chapter 6), case studies (Chapter 6), secondary data analysis (Chapter 7), and content analysis (Chapter 7). Since this is the first chapter to discuss measurement, a comprehensive review of validity and reliability is presented here. As you proceed through the remainder of this book, keep in mind that validity and reliability apply to all types of measurement that are completed in research studies.

Assessing Validity

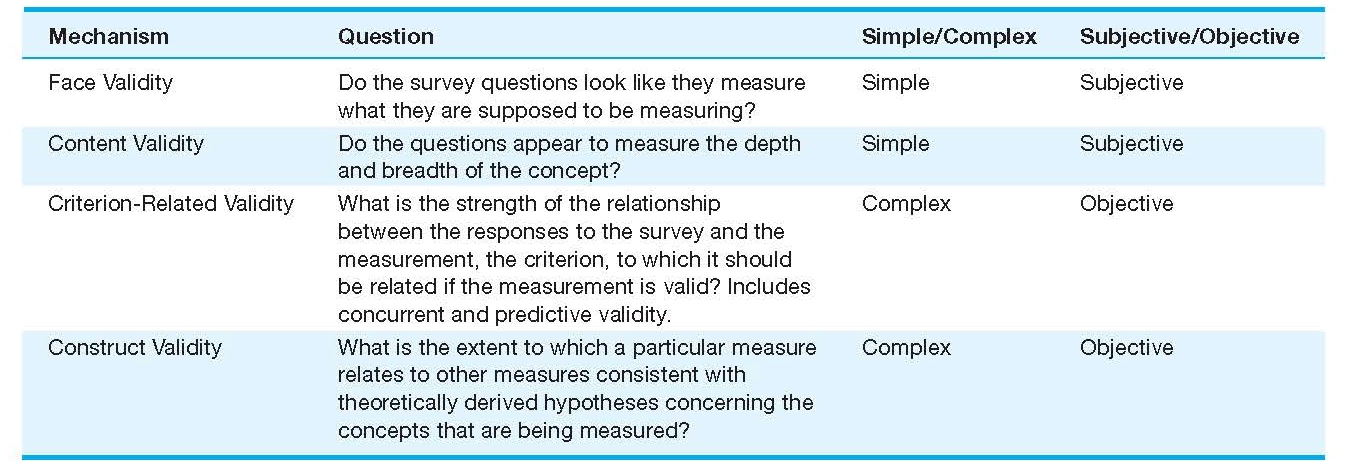

Validity addresses the accuracy of the measurement and refers to the extent to which the survey questions and responses measure what they were supposed to measure. In other words, are the survey questions and responses good indicators of what the researchers are trying to study? Stated another way, are the survey questions and responses measuring what they are intended to measure? There are numerous ways to assess the validity of measures. The ways range from simply asking if the measures seem like logical and common sense ways to measure the concepts and variables (i.e., face validity) to the complexity of determining whether the measures fit the theoretical constructs of the concept being measured (i.e., construct validity). Even though researchers may use sophisticated ways to assess the validity of their measures, concerns about the validity of the measure may still persist because of the complexity of the concepts studied by criminal justice and criminology researchers. In addition, validity is never proven; instead, invalidity is reduced, and when this occurs researchers express greater confidence in their data and the results of their study. There are several ways of assessing if the measures used in a study are valid: face, content, criterion-related, and construct validity. The different means of assessing validity vary by complexity and subjectivity.

Face validity, the simplest and most subjective means to measure validity, assesses whether the survey questions are a logical and common sense way to measure the concept. Basically, face validity involves an assessment of the survey questions to see if on “face value” the questions seem to be measuring the concepts and variables they are supposed to be measuring. Face validity answers the simple question, “Do the survey questions look like they measure what they are supposed to be measuring?” For example, if a researcher is measuring fear of crime, does the survey instrument ask questions about specific types of crime and the level of fear for each? If so, the survey has face validity.

Face validity is sometimes developed based on establishing a consensus among researchers that the measure is a valid way to measure the concept. For example, if researchers generally agree that asking someone “How many times have you been arrested?” is a valid measure of prior arrests, then, until proven otherwise, the question is a valid measure of prior arrests. However, because face validity is entirely a matter of judgment, there can be great disagreement among researchers and consumers of research about whether a survey question has face validity.

Content validity is subjective, just like face validity, but is somewhat more complex than face validity. It occurs when the survey questions measure the full breadth and depth of the concept being studied. For example, let’s say that when you have completed Chapters 1–4 of this book, you are scheduled to take an exam over Chapters 1–4. What if when you take the exam, your professor only asks questions about sampling, which is covered in Chapter 3? You would probably argue that the test was not fair and was not a good measure of your knowledge of Chapters 1–4 because it only covered Chapter 3. What you are stating is that the test, as a measurement of knowledge of the material covered in Chapters 1–4, lacks content validity. In order to have content validity, the test should have included questions over Chapters 1, 2, 3, and 4.

As another example, there exists a traditional measure of fear of crime that lacks content validity. Traditionally, fear of crime was measured in surveys based on the response to the question, “How safe do you feel walking alone in your neighborhood at night?” This question lacks content validity because it does not measure the full breadth and depth of someone’s fear of crime. It is basically limited to fear of street crimes like robbery and assault, but does not include crimes that people fear but occur in their residences, such as sexual assault, family violence, burglary, and theft. Also, the question is limited to your neighborhood, whereas you may have a high level of fear of crime but it is due to getting off late at night from your job and having to walk through a deserted parking garage to get to your car. Furthermore, the question is time dependent, only asking about fear of crime at night.

When it comes to criminal justice and criminology research, content validity is difficult to obtain because researchers are trying to measure complex concepts. When studying criminal offending, it is difficult to ask about all types of crimes; there are just too many. Similarly, when studying drug use, it is difficult to ask about all types of drugs. However, just as discussed with face validity, consensus among researchers is used to determine content validity.

Criterion-related validity is more complex and less subjective than face and content validity. Criterion-related validity is assessed by determining the strength of the relationship between the responses to the survey and another measurement, the criterion, to which it should be related if the measurement is valid. For example, let’s say that you want to create a measure of self-esteem. As previously mentioned in this chapter, the 10-question measure of self-esteem created by Rosenberg in the 1960s is a valid measure of self-esteem. You create a 16-question measure of self-esteem but will want to determine if the measure is valid. You can give a sample of people a survey that includes both the Rosenberg questions and your new questions about self-esteem. You can then determine the relationship between the responses to your measure of self-esteem in comparison to Rosenberg’s questions, the criteria. If individuals that have high self-esteem according to Rosenberg’s measure consistently have high self-esteem according to your new measure of self-esteem, then your measure has criterion-related validity. If individuals have high self-esteem according to Rosenberg’s measure but consistently have low self-esteem according to your new measure, then your measurement of self-esteem lacks criterion-related validity.

As another example, you may be interested in pursuing law school after completing your bachelor’s degree. Admission committees at law schools use the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) to predict success in law school. They prefer to admit students with high LSAT scores because they believe those are the students most likely to do well in law school. If there is a strong relationship between the LSAT score and success in law school as measured by law school grades, then the LSAT has high criterion-related validity. The LSAT is related to something that it should be related to, in this case, law school grades.

There are two types of criterion-related validity: concurrent and predictive validity. A measurement has high criterion-related validity, more specifically high concurrent validity, when there is a strong relationship between a new measure and a measure that is known to be valid. The example above regarding Rosenberg and a new measure of self-esteem is an example of concurrent validity. Concurrent validity occurs when an experimental measure (e.g., your new self-esteem measurement) and a valid measure (e.g., Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale) measure the same thing at the same time (i.e., concurrently).

Concurrent validity is also assessed when a response to a survey item is compared to the same information from a different data source. For example, let’s say your professor asks your current grade point average on a self-administered survey. Then, your professor uses your university’s information system to obtain your official GPA. The more these two numbers correspond (i.e., your stated GPA and your official GPA), the higher the concurrent validity of the survey measurement of GPA. In criminal justice and criminology research, this process can occur to validate survey information that is also stored by criminal justice agencies such as prior arrests, convictions, and incarcerations, to name a few.

Another way to assess concurrent validity is to use what is sometimes referred to as the known group comparison technique. Let’s say that you want to develop a measure of religiosity because you want to study the impact of religious beliefs on delinquent activities. Although valid measures of religiosity exist, you want to develop your own measure. After you have developed the survey questions, you administer the survey to members of the clergy and members of Atheist Alliance International (AAI). If your survey measure of religiosity shows that the members of the clergy have high levels of religiosity and members of AAI have low levels of religiosity, then you have established the concurrent validity of your measure. The items in your survey measurement are measuring what they were intended to measure (i.e., level of religious beliefs). If the measurement doesn’t differentiate the level of religious beliefs between members of the clergy and AAI, then there is something wrong with your survey questions.

Another type of criterion-related validity assesses how accurately a measurement predicts some future, rather than current, outcome similar to the example previously discussed regarding the LSAT as a prediction of law school success. This type of validity is referred to as predictive validity. Let’s say that you develop a set of survey items that is designed to determine if someone will be a successful police officer. A local police department decides to assist you with your study and allows you to issue your survey to the current police recruit academy class of 175 cadets. You track these police recruits for the next three years after completion of the police academy and field training program. If the individuals who scored highest on your survey while in the academy are also the most likely to have received promotions, excellent performance evaluation reviews, and fewer disciplinary infractions, then your measure has predictive validity. Police departments can now use this measurement tool to screen potential police officers with confidence in its ability to predict future success.

We frequently use measures in the criminal justice system to make decisions, including whether a crime can be solved, whether someone should be let out of jail on bail, whether a person should be released from prison on parole, and whether a person should be placed on a general probation caseload or a specialized caseload. These measures are only as good as their level of predictive validity; ability to predict some future outcome. If they have predictive validity, then we can have confidence in the predictive accuracy of the measurement.

Another way of assessing the accuracy of a measure is to determine its construct validity. Similar to criterion-related validity, construct validity is more complex and less subjective than face and content validity. Construct validity assesses the extent to which a particular measure relates to other measures consistent with theoretically derived hypotheses concerning the concepts/variables that are being measured. Since construct validity is based on theory, it is favored by researchers.

For example, prior research has established a relationship between self-esteem and delinquency. Juveniles with high self-esteem are less likely to commit delinquent acts than juveniles with low self-esteem. You want to conduct a research study to test the following hypothesis: There is a relationship between self-esteem and delinquency. As presented in prior examples, let’s say that you want to create your own measure of self-esteem instead of using Rosenberg’s validated measure. You create your new 16-item measure of self-esteem and use a prior validated measure of delinquency. You administer the survey to the 8th graders in the middle school closest to your residence. The results show that those with high levels of self-esteem are less likely to commit acts of delinquency and those with low levels of self-esteem are more likely to commit acts of delinquency. This is exactly what was expected based on your theoretically derived hypothesis regarding the relationship between self-esteem and delinquency. Therefore, your new measure of self-esteem has construct validity. If the survey results would have shown that those most likely to be delinquent also have the highest levels of self-esteem, then your measurement of self-esteem would lack construct validity and the results of the study would be suspect. As depicted in the example, construct validity is based on actual research results and is not obtained until after the data has been collected and analyzed. Other researchers can begin to use your measure of self-esteem because you have shown that it has construct validity.

FIGURE 4.1 | Mechanisms for Assessing Validity

Increasing Validity

Now that we have presented the main approaches to assessing validity, we turn our attention to discussing ways to increase the validity of a survey instrument. As previously discussed, it is certainly reasonable for a researcher to use measures that have already been established as valid. If you are studying victimization on your college campus, it is certainly reasonable to develop your survey based on the National Crime Victimization Survey since the validity of this measurement has already been established. Even though a researcher may be using a previously established measure, there are validity issues that must be addressed in every research study. This section will discuss the major validity issues and the suggested means to overcome them, thereby increasing the validity of a research study. As an educated consumer of research, you should be aware of these issues as you review research reports. One significant validity issue with survey research is whether respondents are telling the truth.

Are the Respondents Telling the Truth? Aiding Respondent Recall Recall that validity is addressing the accuracy of the measurement. Survey responses are usually accurate and truthful when the survey questions ask about a behavior or incident that is easily remembered. Most offenders can easily remember how many times they have been arrested in the past month, but it is more difficult for a drug abuser to remember how many times they have used illicit drugs in the past month. It is likely that the number of arrests in the past month will be a more accurate response than the number of times an abuser has used drugs in the past month.

It is clear that a respondent’s ability to accurately recall events declines over time and accurately recalling events typically takes more time than the few seconds that a respondent has to answer a survey question. As discussed in the chapter opening case study, a major source of error of the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) includes the inability of the respondents to recall in detail the crimes that occurred during the 6 months prior to the interview. The NCVS uses a 6-month reference period. Respondents are asked to report victimization experiences occurring in the last 6 months. Generally, respondents are able to recall more accurately an event that occurred within 3 months of the interview rather than one that occurred within 6 months. Research indicates that assault is recalled with the least accuracy of any crime measured by the NCVS. Recall problems may result in an underestimate of the actual rate of assault.

Survey researchers recognize that memory is less trustworthy than once assumed. In response, strategies have been developed to maximize respondent recall. Survey researchers should be as specific and recent as possible when asking about past events. You can improve accuracy by making the recall period for the survey questions recent. The problem of forgetting becomes increasingly serious as the respondent is asked to recall events stretching over a longer period of time. In addition, the researcher should clearly specify the behavior asked about. The complexity of respondent recall does not mean that survey researchers cannot ask about past events. Instead, survey researchers need to customize questions to shorten the recall period and interpret results cautiously as the recall period grows larger.

In addition, many respondents will telescope their responses. Telescoping occurs when a respondent brings behaviors and actions that occurred outside the recall period into the recall period. For example, let’s say that a person was assaulted 8 months ago and has not been assaulted since that time. The person is answering a survey question that asks “How many times have you been assaulted in the past 6 months?” and the survey respondent answers “one time.” The respondent has telescoped the victimization into the 6-month time frame even though it occurred 8 months ago and was outside the time frame provided by the researcher. Telescoping responses leads to overreporting of recent events and underreporting of distant events.

Are the Respondents Telling the Truth? Asking Embarrassing and Stigmatizing Questions People have a tendency to underreport embarrassing or stigmatizing events (e.g., hitting their children, being a sexual assault victim, and lying on their tax return). Criminal justice research asks about many potentially embarrassing and stigmatizing topics such as criminal offending, victimization, drug use, alcohol consumption, mental illness, and prison rape, to name a few, thus making truthful reporting a challenge in criminal justice research. Respondents may be embarrassed or afraid to give truthful answers and thus, underreport behaviors or attitudes they wish to hide from others. As an educated consumer of research, you need to be aware of and assess the strategies a researcher uses to increase the honesty of survey responses.

Dishonest answers can be difficult to detect, so what strategies exist to increase the honesty and therefore, accuracy of survey responses? First, researchers should inform respondents that their responses are, at a minimum, confidential, and if possible, anonymous. Anonymity infers that the survey respondent’s identity will not be known by the researcher. For example, if a professor hands out a survey in her class to the 150 people in attendance, asks them to respond to the survey and hand them to the end of the seating row where they are picked up by the professor, the surveys are anonymous. The professor does not know who filled out a particular survey. Anonymously collecting survey information, especially if it is of a sensitive or criminal nature, is one of the simplest ways to increase the honesty of responses. Respondents will be more honest regarding sensitive or embarrassing topics when they know their responses cannot be used to harm or embarrass them.

Confidentiality infers that although the researcher may be able to link the information given on a survey or during an interview to the particular research participant who gave it, this link will not be released to anyone else besides members of the research team. For example, a researcher who does face-to-face interviews will certainly know the identity of the respondent but promises to keep the responses in confidence.

Second, survey researchers should try to ensure that sensitive questions are asked in a nonjudgmental way. The researcher should minimize any sense of judgment and maximize the importance of accuracy. Careful attention should be paid to the wording of the introduction and the question to ensure that nothing negative about the behavior is implied to the respondent. The researcher needs to be very careful about any cues respondents are receiving about how their answers will be interpreted. These questions must be asked with great care and great empathy.

Third, the survey researcher should use a self-administered data collection procedure (discussed later in this chapter). It is generally agreed that having respondents answer questions in a self-administered form, on paper or directly into a computer, rather than having an interviewer ask the questions, will produce more honest answers. For surveys dealing with sensitive topics, a mail survey, Internet survey, or group administration survey should be considered. A face-to-face interview can also include some self-administered questions where a respondent is given a set of sensitive questions to answer in a booklet or directly into a computer. A similar strategy can be used with telephone surveys where answers to sensitive questions are entered directly into a computer using the touch-tone feature on the telephone.

Fourth, respondents feel more comfortable answering potentially sensitive questions when the responses are provided as categorical ranges rather than as a specific number. For example, a researcher may get a more honest answer if instead of asking, “What is your annual income?” the researcher provides the respondent with ranges of income from which to choose a response (e.g., less than $20,000, $20,000–$35,000). A respondent’s age can be collected with categorical ranges, instead of a specific age, as well. Especially with demographic characteristics, the more sensitive the question, the better it is to use response categories instead of specific numeric values.

Fifth, the survey researcher can use a randomized response technique (RRT), which allows the researcher to ask about illegal and sensitive behaviors and obtain accurate estimates of the frequency of the behavior. Here’s how it works. Let’s say you are interested in the frequency of excessive force used by correctional officers. You are conducting face-to-face interviews with a sample of correctional officers at a prison unit. Your interviewers define excessive force for each respondent. But instead of your interviewers asking correctional officers the question directly, they give each respondent a randomization device, such as a coin. They ask the respondent to flip the coin. They tell the respondent not to tell them the results of the coin toss. Then they instruct the respondent as follows: “Say Yes if either of the following is true: Your coin came up heads, or you have used excessive force against an inmate in the last month.”

If the respondent says yes, the interviewer does not know which question is being answered. Did the correctional officer say yes because the coin landed on heads or because the officer has used excessive force against an inmate in the last month? If this procedure was repeated with 100 respondents, based on probability theory, you would expect 50 out of 100 to say “Yes,” simply because their coin toss came up heads. Therefore, if you find that 68% of the respondents say “Yes” to this question, you estimate that the 18% above the expected 50% represents correctional officers who used excessive force against inmates in the past month. Thus your finding is that 18% of correctional officers use excessive force against inmates in any given month.

Sixth, although this will be discussed in a later section of this chapter, realize that researchers can use one of the reliability tests, such as split-half reliability, to detect untruthful responses. Researchers ask the same or similar questions in different sections of a survey to determine if respondents were truthful in their responses. Surveys in which the truthfulness of the respondent is questioned should be discarded from the study prior to analysis.

Are the Respondents Telling the Truth? Social Desirability People have a tendency to overreport something if it makes them look good (e.g., willingness to intervene in a crime to protect someone). Survey researchers call this overreporting social desirability bias. Social desirability bias occurs when respondents provide answers to survey questions that do not necessarily reflect the respondent’s beliefs but that reflect social norms. If social desirability bias is widespread, it can have a significant impact on the results of the study.

One of the best examples of social desirability bias is LaPiere’s20 study of attitudes and behaviors towards hotel and restaurant service of Chinese people. Beginning in 1930 and continuing for two years thereafter, LaPiere traveled across the United States in an automobile with a young Chinese student and his wife. The early 1930s was a time when the general attitude of Americans toward Chinese residents was negative and was well documented in several social distance studies completed at the time. There was a national negative stereotype of Chinese citizens at the time, and the social norms of the time were to react negatively to individuals of Chinese descent. Discrimination against Chinese residents was common as well.

LaPiere discovered substantial differences between the stated attitude of survey respondents and actual behavior. During their extensive travels, the Chinese couple was received at 66 hotels, auto camps, and “tourist homes,” and was only refused service at one. Similarly, they were provided service in 184 restaurants and cafes throughout the United States and were never refused service. To assess differences between stated attitude and behavior, LaPiere completed a mailed survey six months after departure from 22 of the hotels and 43 of the restaurants they visited and asked “Will you accept members of the Chinese race as guests in your establishment?” To his bewilderment, 91% of the hotels and 93% of the restaurants answered “No,” even though he had a personal experience with each of the establishments where all but one provided service to the Chinese couple. Simply stated, he discovered what people say is not always what they do.

LaPiere’s study certainly illustrates the difference that occurs sometimes between stated attitudes on surveys and actual behaviors. Just because someone says they would or would not do something on a survey, does not necessarily mean that will relate to the respondents’ actions. In this case, LaPiere observed substantial discrepancies between attitudes and behaviors.

This study is also a reflection of social desirability bias. At the time, the social norms dictated a negative reaction to individuals of Chinese descent. When presented with a question about whether they would provide service to someone of Chinese descent, almost all of the respondents reflected the social norms at the time and responded “no.” As stated above, social desirability bias occurs when respondents provide answers to survey questions that do not necessarily reflect the respondent’s beliefs but instead reflect social norms, and that is certainly the case in LaPiere’s study.

In order to detect social desirability, some survey researchers include the same or similar questions in different sections of a survey to determine if respondents were truthful in their responses, as previously mentioned. Researchers can also build in questions that are likely to identify respondents who are giving socially desirable answers. For example, the researcher may ask survey questions that include words such as “always” and “never.” People rarely “always” or “never” do or feel something, so respondents who routinely select these responses are probably depicting social desirability bias. Another way to detect social desirability bias is to include unlikely choices in the closed-ended survey questions. Surveys in which the truthfulness of the respondent is questioned should be discarded from the study prior to analysis.

CLASSICS IN CJ RESEARCH

The Relationship Between Correctional Officers’ Race and their Attitudes

Research Study21

Historically, correctional officers were white, uneducated, conservative males who lived in the rural areas where most prisons were located. Beginning in the 1950s, prison populations started to change as more urban blacks were sent to prison. Racial tensions between inmates and guards escalated. Black inmates had not only become more prevalent in number, they stood as a unified group against the guards who perceived them as a greater threat compared to the white inmates. Many reformers advocated increasing the number of black prison guards as a way to reduce conflict and antagonism between guards and inmates. The assumption was that black guards would be able to relate better to the black inmates because they shared similar backgrounds. Whether or not the attitudes held by black prison guards toward inmates were any different from those held by white guards remained an untested assumption until the late 1970s when James Jacobs and Lawrence Kraft conducted an empirical test of correctional officers’ attitudes.

The authors tested the following five hypotheses:

1. Black guards have more sympathetic attitudes toward inmates compared to white guards.

2. Black guards are more supportive of rehabilitation compared to white guards.

3. Black guards convey less support for their superiors compared to white guards.

4. Black guards are less committed to institutional goals compared to white guards.

5. Black guards are less committed to their occupations compared to white guards.

Research Question

Is there a relationship between correctional officers’ race and their attitudes toward inmates, correctional goals, administrators, and correctional officer roles?

Methodology

The authors administered a survey to a sample of 252 guards from Stateville and Joliet prisons who were attending in-service training. Both prisons were maximum-security facilities within seven miles of each other. Three-fourths of the inmate populations in both prisons were black, and most of the prisoners came from the Chicago area (the prisons were 35 miles southwest of the city). At the time the survey was administered, 12% of the correctional officers employed by the Illinois Department of Corrections were black and most of them were working at Stateville and Joliet.

The survey was administered to guards while they attended in-service training at the Correctional Academy between the summer of 1974 and fall of 1975; 165 white guards and 66 black guards completed the survey; 21 guards were excluded from the sample because they did not indicate their race and/or rank on the questionnaire. Prison guards were group-administered an anonymous survey and asked to respond to a series of questions that consisted of both closed-ended and open-ended questions.

Specifically, inmate orientation consisted of a 10-item measure, one question open-ended and the other nine closed-ended, which asked questions such as, “Inmates try to take advantage of officers whenever they can.” Job orientation consisted of a 7-item measure, which asked all closed-ended questions such as, “Although understanding may be important in helping inmates, what is really needed is strictness.” Staff orientation was a 3-item measure, all closed-ended questions such as, “When I began, the veterans were friendly and helped me learn.” System orientation was a 5-item measure, one question open-ended and the other four closed-ended, such as, “Why are there so many members of minority groups in prison?” Job commitment was a 9-item measure with all closed-ended questions such as, “Thinking ahead five years from now, do you think you will still be a correctional officer?”

Results

The results of the study for each hypothesis are presented below.

1. Hypothesis: Black guards have more sympathetic attitudes toward inmates compared to white guards.

Study finding: Black prison guards did not express attitudes that were more sympathetic toward inmates compared to white guards. The responses of black guards to several questions actually revealed less sympathy. The hypothesis was rejected.

2. Hypothesis: Black guards are more supportive of rehabilitation compared to white guards.

Study finding: Black and white prison guards both indicated that rehabilitation was the primary purpose of prison, but when asked what the “primary purpose of prison should be,” more black guards than white guards chose punishment. The hypothesis was rejected.

3. Hypothesis: Black guards convey less support for their superiors compared to white guards.

Study finding: Black prison guards responded more favorably to their superiors than white guards even though most of the prison administrators and supervisors at the two prisons were white. The hypothesis was rejected.

4. Hypothesis: Black guards are less committed to institutional goals compared to white guards.

Study finding: Black officers do not support a more relaxed correctional process. The majority of both races disagreed with the statement that “correctional officers should be rough with inmates occasionally to let them know who is boss,” but blacks more often gave approval to the statement. The hypothesis was rejected.

5. Hypothesis: Black guards are less committed to their occupations compared to white guards.

Study finding: The responses of both black and white guards indicated a strong sense of institutional commitment. Two-thirds of the guards sampled responded that they planned to be working at the prison for at least the next five years. Many of the guards expressed a preference for their current occupation over other alternative options such as private security and police work. The hypothesis was rejected.