7 Teaching Empirical Legal Research

Empirical legal research teaching takes many forms: reference meetings, workshops, research guides and blogs, legal research courses, and more. While law libraries traditionally relied on social science departments and subject librarians to provide data and social science training, that is changing (Reeve & Weller, 2015; Tenopir, et al., 2019; see also, Whisner, 2016). Law librarians are now teaching patrons how to plan for empirical research, critically read social science journal articles, find data and statistics, and more.

This chapter focuses on empirical research planning, reading, and data finding as core teaching services. Additionally, the chapter discusses open access teaching materials, library research guides, and blogs. The chapter concludes with a model for empirical legal study design as a specialized legal research course.

Chapter learning objectives

- Explain empirical legal literature searching as a two-step process

- Identify nine elements of a typical empirical legal research journal article

- Demonstrate four types of data sites

- Locate empirical legal research guides, blogs, and resources

- Conceptualize empirical legal research as a specialized legal research course

Abbreviations and specialized terms

American Association of Law Libraries (AALL), Boolean operators, codebook, data distribution, data repositories, dependent variables, disciplinary research, histogram, hypothesis, independent variables, interactive data-charts sites, interdisciplinary research, numeric data, population research guides, raw data sites, research guide, research question, sample, search term worksheet, statistics and secondary statistical analysis sites, string data, summary statistics, topic selection

Teaching Empirical Research Planning

As a summer law firm associate, a student researcher should create a plan before commencing database research. Robert Linz teaches this skill as a five-part process beginning with problem analysis and concluding with a resource citation list (2022). The first part centers around six questions: 1. What are the material facts? (e.g., who is involved?); 2. What is the legal issue?; 3. What is the area of law?; 4. What is the jurisdiction?; 5. What are some initial search terms?; and 6. What assumptions am I making and questions do I still have? (Linz, 2022). Empirical legal research involves the same detailed planning.

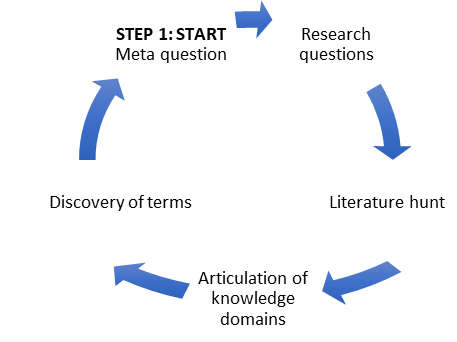

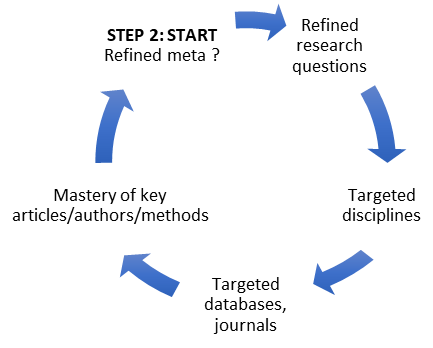

Law librarians can teach empirical research planning as a six-part process: 1) topic selection, 2) background research, 3) literature review research, 4) research study design, 5) research data/information collection, and 6) research reporting, or scholarly communication. Background research can be taught as a two-step exercise. Step one involves exploratory work that might not make it into the paper, presentation, article, etc. Step two requires targeted searching for articles, books, and resources that will ground the written literature review.

7.1 Multi-step background research process

In addition to teaching research as a multi-step process, law librarians can engage empirical research students in short exercises to promote deeper thinking about their topics’ contours, disciplinary roots, and framing language.

Patrons should explore the contours of the subjects that interest them before they commence database research. This can look like a journalistic exploration of the who, what, when, where, how, and why. For instance, if a patron is interested in how zoning impacts school segregation, they should consider which people are most involved (i.e., who; e.g., homes with and without children), which dwellings are involved (i.e., what/where; e.g., single family units, multifamily units, apartment buildings, retail spaces), what time periods they want to study, and more. In journalistically exploring the topic, especially through conversations with others, patrons can discover aspects of the phenomenon that had not occurred to them, such as how retail zoning affects school segregation.

Patrons should engage in disciplinary thinking to identify databases and other resources. Empirical topics usually involve non-law fields such as economics, psychology, or sociology. Patrons should consider which disciplines or professions study their proposed topics. At the broadest level, patrons can locate their subjects within the sciences, social sciences, and/or humanities. At a narrower level, patrons should consider how various disciplines would view the topic. For instance, the subject of land contracts in central Africa could be viewed via history (e.g., pre- and post-colonial landholding), gender studies (e.g., women’s land and property rights), and economics (e.g., profit margins of smallholder farms versus coffee plantations), etc. Librarians can guide individual patrons and workshop participants through sample topics and social science library guides. Librarians can also encourage patrons to think of interdisciplinary research as requiring two types of searching: disciplinary and interdisciplinary research (e.g., Energy Research & Social Science journal).

In 2012, I joined the founding board of a new interdisciplinary journal: Energy Research & Social Science (ERSS). Before that, I had published in interdisciplinary journals, including gender studies and law journals. But I had not contemplated why interdisciplinary journals are launched in the first place. We started our journal for four reasons. First, we cared about the future of energy consumption and policy, and wanted to support useful research on climate change mitigation and adaptation (Sovacool, et al., 2015). Second, we believed that changes to energy systems required more than new technologies; they required human understanding, investment, and participation. Third, we felt that energy researchers—including energy journal editors—were undervaluing social scientific energy research. Fourth, we wanted to build an interdisciplinary research community to encourage cross-fertilization between the social and physical sciences. As the founding board, we wrote articles identifying potential research areas. I wrote the gender studies agenda-setting article (Ryan, 2014). I also served as Associate Editor for a year, overseeing the assignment of dozens of manuscripts to peer reviewers. And, I wrote a response article, at the invitation of our editor, to a long-unpublished piece by a renowned “physicist-turned-political scientist” and emeritus U.C. Berkeley professor (Sanders, 2018). My team analyzed why this piece was rejected a quarter-century earlier despite its merit and what it had to offer energy researchers today (Ryan, Hebdon, & Dafoe, 2014). Holistically, my experience taught me to consider the reasons each journal exists, how it works behind the scenes, and the impact of what it and its peer journals publish and refuse to publish in a given era.

Patrons can prepare for formative research by identifying subtopics, research questions, and search terms. Law librarians can teach patrons typical Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR), help them craft a table of search terms, and encourage them to view their initial research as an exercise in synonym-finding. That is, an important outcome of groundwork searching is the identification of terminology for future searching. Librarians can ask patrons to complete search worksheets. While these are a staple of library science curriculum, they will be unfamiliar to some law patrons.

| energy law | climate change | cryptocurrency | |

| Synonym via brainstorming | energy policy | global warming | blockchain |

| Synonym via brainstorming | resources law | greenhouse gas emissions | digital economy |

| Synonym via brainstorming | energy trade law | melting glacier | bitcoin |

| Synonym from background searching |

7.3 Search worksheet for a paper on cryptocurrency, climate change, and energy law

Once librarians have taught patrons how to prepare for background research, they can help support their literature review research, research study design, research data/information collection, and research reporting, as described throughout this book. This includes critical reading of social science research.

Teaching Critical Reading of Social Science Research

Law librarians can teach law students and legal professionals how to critically read social science articles by focusing on nine aspects of those articles. First, the reader should examine the background literature cited in the article, noting: theories, historical developments and debates, prior research, understudied topics or questions, and recommended future research avenues. Second, the reader should note all hypotheses (H1), null hypotheses (H0), and research questions (RQ). Legal research instructors can advise students to highlight these statements. Third and relatedly, the reader should observe the dependent variables, or outcomes under study (e.g., defamation jury award size), and the independent, correlational, or causal variables (e.g., plaintiff gender, medium used to defame). Fourth, the reader should discern the details of the population under study and the sample included in the research, including the size and characteristics of the sample, and the sampling methods used by the researcher. Fifth, the reader should scrutinize the methods used to study the phenomenon. Librarians should encourage readers to move beyond a quantitative versus qualitative mindset to an analysis of the myriad methods that could and should be used to study the topic (e.g., surveying, interviewing, observing; e.g., single methods, multiple/mixed/triangulated methods).

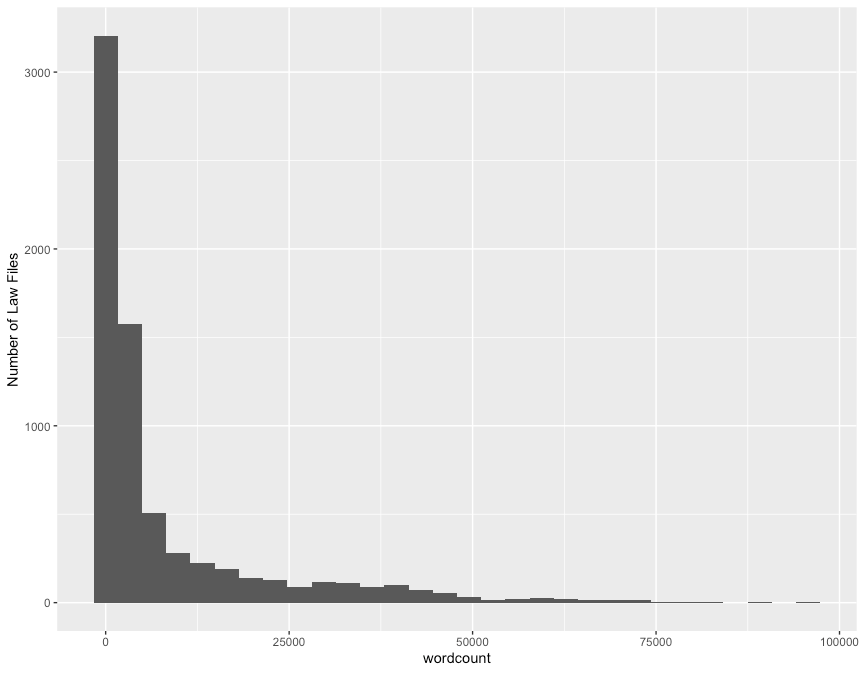

The first five considerations involve the study basis and background. The final three questions concern the researchers’ findings and interpretation of the study results, including recommendations for future studies. Sixth, the reader should note the basic features of the data including its distribution (e.g., bell curve) and summary statistics (e.g., mode, median, mean, standard deviation). Librarians can anticipate that some patrons will find typical tabular and graphical presentations of this information off-putting (Epstein & Martin, 2014) and encourage patrons to unpack dense summary statistics tables to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of the data. For instance, the histogram below shows the word-count size of files in a dataset containing approximately 7,000 legislative acts; most acts were less than 12,500 words and very few were over 50,000 words.

7.4 Word-count distribution of files in a legislative acts dataset (Ryan, Hong, & Rashid, forthcoming)

Seventh, the reader should carefully analyze the findings, including purported relationships among quantitative variables (e.g., as depicted in scatterplot graphics), narrative evidence of community practices, etc. In quantitative correlational studies, each finding should have two parts: an abbreviation and number indicating the relationship strength and quality (e.g., strong positive relationship, such as an R2 of .8) and an abbreviation and number indicating the researcher’s confidence in applying that finding to the population (e.g., finding is highly statistically significant/null hypothesis is highly unlikely to be true, p < 0.01). Eighth, the reader should critically engage the researcher’s sense-making, discussion, and conclusion. At this point, the reader should talk back to the article, noting methodological weaknesses and posing alternative explanations for findings. Readers should ask tough questions of quantitative and qualitative studies, such as: are the variables more complex than the researcher suggests? did the researcher miss important participants? did the researcher introduce bias through survey or interview questions, site selection, or any other methodological choices? could more have been done to reliably and validly study this topic? (Schutt, R. K. 2018). Ninth, the reader should engage with the cited references, noting predominate researchers, the dates of key publications, recurrent journal names, etc.

7.5 Nine-point checklist for critical reading of social science articles

- Examine the background literature

- Note all Hs and RQs

- Observe all dependent and independent variables

- Discern population and sample characteristics and sampling methods

- Scrutinize the study methods

- Note data features including distribution and summary statistics

- Analyze findings, including quantitative relationships and narrative evidence of practices

- Talk back to the discussion and conclusion

- Engage the reference section and cited resources

In a multi-week class or workshop, law librarians can have students present their best formative research discovery—usually a peer-reviewed social science journal article—using the nine-point checklist above. Or, students can engage in informal sharing around three questions: 1) what are you bringing today?, 2) why is it a very good (article) for your research?, and 3) how did you find it (e.g., search string, database).

Teaching Data Finding

Law librarians can teach data finding in many formats, including workshops, class sessions, and online tutorials. Instruction can focus on four types of data sites: 1) Interactive data-charts sites, 2) Raw data sites, 3) Data repositories, and 4) Statistics and secondary statistical analysis sites.

Interactive Data-Charts Sites

Interactive data-charts sites enable researchers to view and download both raw data (e.g., in an Excel file) and charts. The World Bank indicators site, at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator, features variables of interest to empirical legal researchers, offers several chart options (e.g., line, bar, map), and generally functions well. The Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer, at https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/, is similarly relevant and user-friendly. The U.S. Census Bureau data site, at https://data.census.gov/cedsci/, features innumerable variables and charts, including population estimates needed for many empirical legal research studies. However, the Census Bureau’s vast holdings can be difficult to navigate, and the site is more appropriate as a stand-alone workshop or follow-up to an exploration of a refined data-charts site. Instructors can also teach subscription data-charts tools such as PolicyMap and TRACFed.

Raw Data Sites

Raw data sites contain data files for download but do not have built-in charting capabilities. As a result, students will need to use data and/or statistics software—Excel, Stata, SPSS, R—to engage with these datasets. Law librarians can teach raw data sites in two parts: documentation and data browsing.

First, we can teach students to critically read the documentation, or codebooks, accompanying data. Codebooks list and describe the variables included in datasets. Minimally, each variable description should include the name of the variable, a definition of the variable, and its format. The two basic formats are numeric and string. Numeric data includes only numbers. Some software packages allow researchers to record the numeric data type as nominal (i.e., placeholder number, e.g., female = 1), ordinal (i.e., scale number, 10 = definitely recommend), and interval-ratio or count (i.e., real world number, e.g., age = 45). String variables can include letters and symbols. Codebooks should identify numeric and string variables, but they can be idiosyncratic and cryptic. For instance, the codebook for the “Attributes of U.S. Appeals Court Judges, 1801-2000” dataset includes the variable “aba,” defined as American Bar Association rating, and formatted as “abafmt” (Gryski & Zuk). A footnote indicates that ABA ratings include “exceptionally well qualified, well qualified . . .” etc. These are alphabetical, or string variables. Codebook teaching does not require data/statistics software whereas data browsing instruction does.

To prepare for data browsing sessions, law librarians should select simple datasets involving a few variables. Since the late 1990s, professor Aswath Damodaran has maintained a site of instructional datasets through the Stern School of Business at New York University (Damodaran, 2022). Dr. Damodaran’s datasets are typically downloadable as .xls files with embedded codebooks, citations to the data sources, sheets of data for individual variables, built-in calculators, and more. Librarians can show patrons how to download, open, and browse these datasets using basic sorting and analysis tools (e.g., Excel’s SUM function).

Data Repositories

Data repositories come in many forms. Some researchers maintain their datasets on their faculty websites. Some journals publish datasets as supplements to articles on their websites. Perhaps the largest dataset repository is the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan. Over the past few decades, the repository has developed detailed procedures for depositing data. However, its holdings include pre-Internet data and datasets deposited before formal rules were developed (or in spite of the rules). Law librarians can demonstrate the value and challenges of using large repositories via an ICPSR search of common legal terms such as contracting or zoning. The results, which can be organized using left-side facets, will include data in various formats (e.g., R), codebooks, related articles, grant funding information, and more. The data can be restricted, in unfamiliar formats, partly missing, etc. Law librarians can use these challenges to teach the need for time management and follow-up research.

Statistics and Secondary Statistical Analysis Sites

Statistics and secondary statistical analysis sites rarely include the underlying data. Nonprofit justice organizations produce such sites. For instance, the NAACP maintains a criminal justice fact sheet that includes U.S. law enforcement and incarceration statistics (e.g., at https://naacp.org/resources/criminal-justice-fact-sheet). The Vera Institute publishes an annual people in U.S. jails and prisons report (e.g., https://www.vera.org/publications/people-in-jail-and-prison-in-spring-2021). The CATO Institute issues an annual Human Freedom Index report of national-level personal, civil, and economic freedoms (e.g., https://www.cato.org/human-freedom-index/2021). Law librarians can teach patrons that these resources exist but must be critically evaluated. Patrons should research the ideology of the underlying organization or contributors using resources such as SourceWatch (i.e., https://www.sourcewatch.org/). Patrons should also carefully review related codebooks, methodology footnotes, and other evidence of how the researchers gathered data, generated statistics, and reported their results. Patrons should be reminded that statistics and secondary statistical analysis sites are not peer-reviewed and are mission-driven rather than scientifically objective.

Teaching through Research Guides, Blogs, & Library Resources

While empirical research planning, critical reading, and data finding are core offerings of an empirical training program, there are many other topics to cover. Law librarians use research guides, blogs, and other library resources to broaden the scope of our empirical instructional offerings.

Many academic law libraries maintain dedicated empirical legal research guides. For instance, the University of Arizona Law Library guide covers empirical journals and blogs, professional organizations, selected datasets and statistics, university rules and resources for conducting human subjects research, and more. Georgetown Law Library’s guide features introductory readings, research design and data collection planning resources, methodology articles and books, search strategies and sites, selected datasets and statistics, and statistical software and data analysis tool recommendations. Beyond dedicated research guides, law librarians include empirical resources in topical and course research guides. For instance, North Carolina Central University law librarian Zanada Joyner included the SCOTUSblog statistics page (i.e., https://www.scotusblog.com/statistics/) in her Supreme Court Seminar research guide (https://ncculaw.libguides.nccu.edu/SupCourtSem2016).

7.6 Law Librarian Spotlight: Zanada Joyner

Zanada Joyner entered the law librarianship profession with a background in teaching and education. She holds a B.A. in English from Loyola University New Orleans, an M.A. in Education from the University of Mississippi, a J.D. from Loyola University New Orleans College of Law, and an M.L.I.S. from Rutgers University, where she completed an internship at the Rutgers Law Library (Newark). Ms. Joyner taught English and language arts courses before taking a position with the University of Georgia Law Library as the Research and Instruction Services Librarian. She also worked as a Reference Associate at Loyola Law Library (New Orleans) and served as a judicial law clerk for New Jersey Superior Court Judge Thomas S. Smith, Jr. (retired). In her current position, Ms. Joyner is the Senior Reference Librarian at North Carolina Central University where she teaches First Year Legal Research and Advanced Legal Research courses in addition to conducting tours and working with students and faculty on research projects. She maintains library research guides on subjects ranging from sexual identity and the law to academic affairs. Ms. Joyner is the co-author of Introduction to Law Librarianship (2021). She is currently working on diversity projects, designing effective legal research rubrics, and empowering future entrepreneurs. An active member of the American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) and the Southeastern Chapter of the American Association of Law Libraries SEAALL), Ms. Joyner is involved in various committees, caucuses, and special interest sections within AALL. Ms. Joyner was awarded the 2018 AALL Minority Leadership Development Award and the 2022 Andrews Legal Literature Award. (Joyner, 2022)

Law libraries and academic groups publish diverse empirical blogs. Harvard and Yale Law librarians have written blogs on empirical legal research conferences, workshops, and other resources (i.e., https://etseq.law.harvard.edu/category/empiricism/; https://library.law.yale.edu/blogs). The RIPS Law Librarian blog, maintained by the Research Instruction and Patron Services Special Interest Section (RIPS SIS) of the American Association of Law Libraries (AALL), has a category for empirical research notes (i.e., https://ripslawlibrarian.wordpress.com/category/empirical-legal-research-2/page/2/). Leading legal researchers maintain the Empirical Legal Studies blog, which features calls for papers and new research (i.e., https://www.elsblog.org/the_empirical_legal_studi/). The Stanford Law Library maintains a list of additional current awareness tools via its empirical legal research resources and strategies guide (i.e., https://guides.law.stanford.edu/c.php?g=685018&p=4863036).

Librarians and other instructors are beginning to build repositories of online empirical legal research teaching materials. In addition to library websites, law librarians share their teaching materials via the ALL-SIS Sourcebook for Teaching Legal Research, RIPS-SIS National Legal Research Teach-In Kit, and FCIL-SIS Syllabi and Course Materials Database (see, e.g., https://www.aallnet.org/ripssis/education-training/teach-in/). The Center for the Study of Law & Society at Berkeley Law posts videos, slides, and other materials from its Empirical Research Methods Workshops (i.e., https://www.law.berkeley.edu/research/center-for-the-study-of-law-society/empirical-research-methods-workshops/).

Teaching Empirical Legal Study Design as a Specialized Legal Research Course

Empirical legal research can be taught as a specialized legal research course. The course can take one of three formats: 1) readings in empirical legal research, 2) basic empirical legal research skills, and 3) study design. The first two formats are the subject of this book. Chapter 1 focuses on historical readings while the remaining chapters highlight exemplary and unique empirical legal research. Chapters two through six highlight basic empirical legal research skills, including literature review skills and quantitative instrument design fundamentals.

Empirical legal research can also be taught as a study design course, or course that results in a plan for a study but not the completed research. The benefits of this approach are three-fold. First, as a legal research offering, the course is less likely to duplicate other law school courses. Second, an empirical legal study design course can prepare law students for special topics courses such as Law & Economics, and for independent study projects centered around an original research study. Third, the study design focus promotes student-centered teaching and flipped classroom pedagogy.

As a library study design course, empirical legal research can focus on six core skills: 1) understanding the field; 2) designing meta-questions, hypotheses, and research questions; 3) conducting literature review research and writing; 4) understanding and selecting research methodologies; 5) finding data, data collection instruments, or literature on instrument design; and 6) navigating human subjects research. Optional sessions can include research grant writing and guest lectures by empirical researchers. Skills-focused course texts can include Epstein and Martin’s An Introduction to Empirical Legal Research (2014) and Lawless and Robbennolt’s Empirical Methods in Law (2016).

A study design course can center student experiences through weekly freewriting, informal sharing, presentations, and focused writing assignments. This technique is most effective when students are required to select a course-long research topic. Early in the course, students can discuss their empirical interests and research topics. Students can then work in dyads and small groups to refine their meta-questions, hypotheses, and research questions. Students can pair-and-share their search worksheets and strategies. Mid-course, instructors can schedule computer lab time for focused searching. As follow-up, students can present found articles to demonstrate their critical reading skills. Once students have built bodies of research, they can deliver short presentations about their literature reviews. Students can also discuss the significance and impact of their proposed research, or how their work builds off of existing literature. Late-course, instructors can have small groups deconstruct selected empirical legal research methodologies. Individual students can present their selected methodologies, and the class can offer constructive feedback on these methods and suggestions for finding existing data and instruments. The course can conclude with formal presentations of the students’ research study designs and class discussion of the future of Empirical Legal Studies.

Reflection Questions

- Prior to reading this chapter, what were your main focuses when reading social science article? Have your focuses changed? If so, how? If not, which facts or ideas in this chapter reinforced your existing critical reading practices?

- How do you plan for research? What advice would you offer beginning researchers as they prepare to conduct database research?

- How would you explain the shortcomings of secondary statistical analysis, or writings about statistics, to newer social science researchers?

- Which topic of a research study design course would be your favorite to teach? Why?

References

Damodaran, A. (2022). Data: Current. https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datacurrent.html

Epstein, L., & Martin, A. D. (2014). An introduction to empirical legal research. Oxford University Press.

Gryski, G. S., & Zuk, G. (n.d.). A multi-user data base on the attributes of U.S. appeals court judges, 1801-2000 [codebook], https://artsandsciences.sc.edu/poli/juri/auburn_appct_codebook.pdf

Joyner, Z. (2022, June 12). Personal communication with Adrienne Kelish [attorney and law librarianship student and research assistant at the University of North Texas].

Lawless, R. M., & Robbennolt, J. K. (2016). Empirical methods in law (2nd ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Linz, R. (2022). Research notebook template. 2022 National Legal Research Teach-In Kit. American Association of Law Libraries.

Reeve, A. C., & Weller, T. (2015). Empirical legal research support services: a survey of academic law libraries. Law Library Journal, 107(3), 399-420.

Ryan, S. E. (2014). Rethinking gender and identity in energy studies. Energy Research & Social Science, 1, 96-105.

Ryan, S. E., Hebdon, C., & Dafoe, J. (2014). Energy research and the contributions of the social sciences: A contemporary examination. Energy Research & Social Science, 3, 186-197.

Ryan, S. E., Hong, L., & Rashid, M. (forthcoming). From corpus creation to formative discovery: The power of big data-rhetoric teams and methods. Review of Communication.

Sanders, R. (2018). Gene Rochlin, who warned of overreliance on technology, dies at 80. Berkeley News, https://news.berkeley.edu/2018/12/04/gene-rochlin-who-warned-of-overreliance-on-technology-dies-at-80/

Sovacool, B. K., Ryan, S. E., Stern, P. C., Janda, K., Rochlin, G., Spreng, D., Pasqualetti, M. J., Wilhite, H., & Lutzenhiser, L. (2015). Integrating social science in energy research. Energy Research & Social Science, 6, 95-99.

Schutt, R. (2018). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. Sage.

Tenopir, C., Allard, S., Baird, L., Sandusky, R. J., Lundeen, A., Hughes, D., & Pollock, D. (2019). Academic librarians and research data services: Attitudes and practices. IT Lib: Information Technology and Libraries Journal, 1, 24-37.

Whisner, M. (2016). Practicing reference . . . Data, data, data. Law Library Journal, 108(2), 313-321.