3 Empirical Legal Research Literature Reviews

Like all law librarians, empirical specialists help patrons collect and organize research information. Some of this work leverages skills emphasized in library and information science programs including: finding relevant databases, crafting flexible search strings, and assessing the quality and usefulness of retrieved sources. But empirical legal bibliographic work requires more than foundational skills. It requires specialized conversations and planning.

Social science, science, and humanities journals are more varied than law reviews. As a result, empirical literature reviewing requires a tailored initial discussion of goals and preferences. Empirical research is hosted in a variety of databases, each idiosyncratic, and law librarians must learn how to demonstrate these databases to patrons. Once relevant materials are retrieved, librarians should be prepared to help patrons evaluate their rigor and quality.

Chapter learning objectives

- Describe common social science literature review types

- Assist patrons in developing a literature review outline

- Develop strategies for finding social science research articles

- Determine if resources are peer reviewed and appropriately located on the evidence pyramid

Abbreviations and specialized terms

agenda setting literature review type, chronological literature review type, comprehensive topical literature review type, debate literature review type, EBSCOHost, hypothesis, literature review, meta-analysis, national scholarly association, normative writing, peer review, research question, SSRN, systematic review, Ulrichs, Web of Science/Web of Knowledge

Literature Review Goal Setting and Planning

Like law review articles, empirical literature reviews should follow a plan and be well-organized. Law librarians can help empirical and non-empirical patrons improve their research through goal-setting and planning.

The goal of most empirical work is to answer a research question or test a well-reasoned premise (i.e., hypothesis). Empirical research is less likely to be persuasive or normative than law review articles. So, law librarians should encourage patrons to frame their literature review goals in terms of hypotheses or research questions. If the research has not reached the point where the researcher can articulate one of these statements, the law librarian can still describe common literature review structures and ask the patron which one sounds most appropriate for the current project.

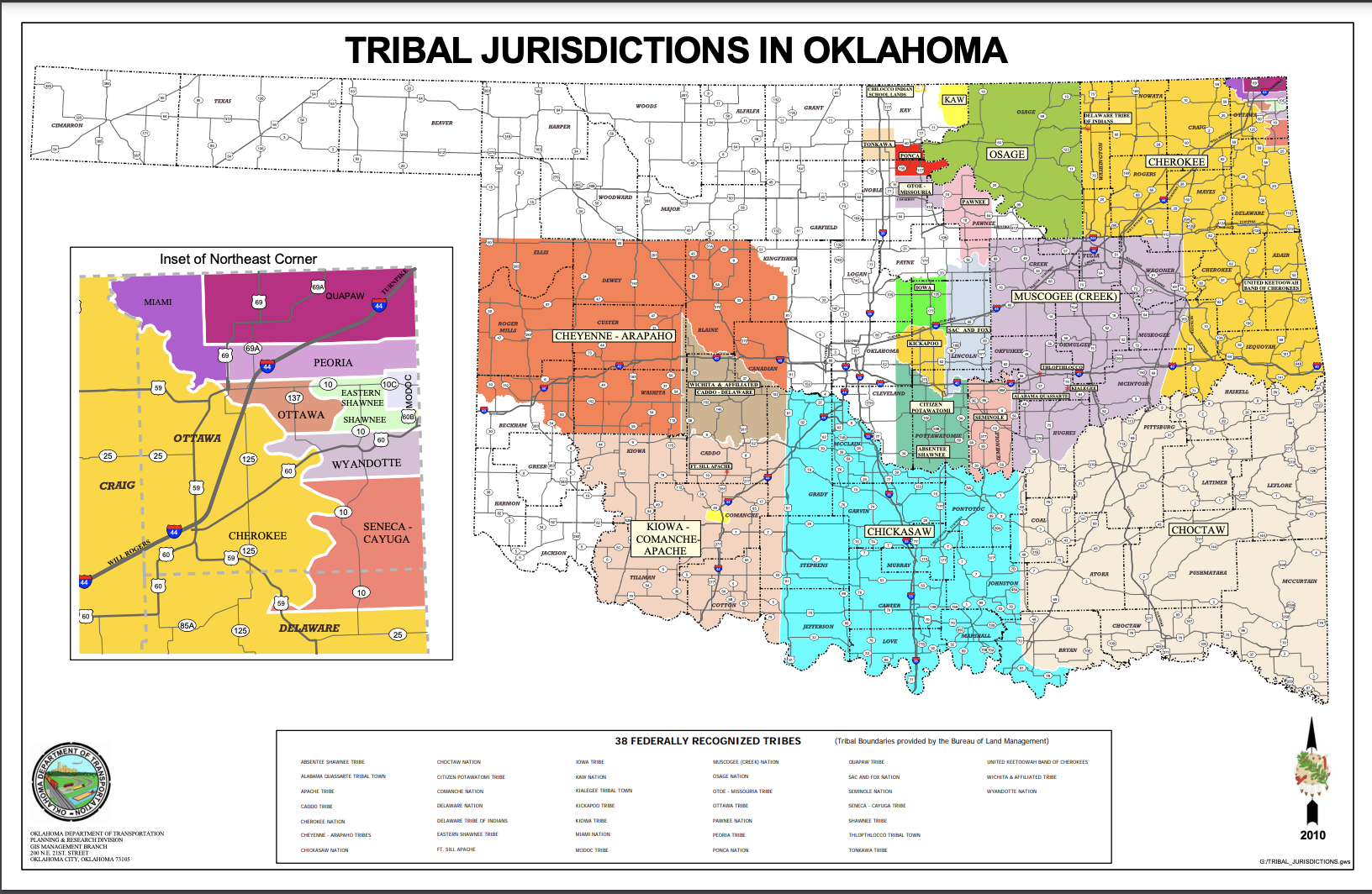

While there is great variety in social science literature reviews, law librarians can use four common types—chronological, comprehensive topical, debate, and agenda setting—to guide formative patron conversations. The chronological social science literature review most approximates “history of” law review articles (e.g., Williston, 1888). When presenting research chronologically, the researchers should indicate the inclusive years in the article and its abstract and explain the benefit of reviewing the history of the phenomenon (Ryan, Behpour, Bonds, & Xiao; e.g., Arias-Londoño, Montoya, & Grisales-Noreña, 2020). Once patrons have conducted preliminary research—sometimes as a search performed with the librarian—they should be able to articulate why a historical approach and a certain timeframe meet their research goals. For law students that start with an interesting case, such as McGirt v. Oklahoma, a chronological approach can be a bridge between the history described in the opinion and in historical social science research.

3.1 Legal Touchstone: McGirt v. Oklahoma

In McGirt v. Oklahoma, the Supreme Court ruled that Oklahoma does not have jurisdiction to prosecute certain crimes committed by Native American Tribal [sic] members on reservation land (2020). Under the Major Crimes Act (MCA), “any Indian who commits certain enumerated offenses within (the) Indian country shall be subject to the same laws and penalties as all other persons within the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States” (18 USC §1153(a)). Through a series of treaties beginning after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Congress established a reservation for the Creek Nation in what is now Oklahoma. Along with other Native American lands, this area encompasses the eastern half of the state. Petitioner Jimcy McGirt was found guilty in an Oklahoma district court of three serious sexual offenses. He appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court on the grounds that because he is a member of the Seminole/Creek Nation and his crimes occurred on Creek land, his case should not have been heard in federal court. In a five-justice majority opinion written by Justice Gorsuch, the Supreme Court found that Oklahoma, with the support of Congress, had been overstepping its boundaries by prosecuting Indians [sic] in state courts. The court reasoned that while Congress has allowed states to reduce Native American Nation jurisdiction, Congress has not fully withdrawn its promises to these Nations and the federal courts are bound to recognize what remains of tribal [sic] sovereignty and jurisdiction. Chief Justice Roberts wrote a dissent joined by Justices Alito, Kavanaugh, and Thomas (in part). The dissent raised concerns over the jurisdictional boundaries of the Creek reservation, arguing that Congress had disestablished the reservation more than a century ago. The dissent further argued that the majority’s misreading of historical documents and events would have a destabilizing effect on the governance of eastern Oklahoma. The dissent acknowledged that Native Americans affiliated with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations comprise 10-15% of the state’s population. In 2022, the Supreme Court narrowed the scope of McGirt for prosecutions of non-Indians on tribal lands (Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 2022). Justice Kavanaugh delivered the opinion of the 5-4 court with Justice Gorsuch writing for the dissent.

Research note: While Indian is a pejorative and incorrect term for descendants of certain groups that lived in the U.S. before it was colonized by Europeans, Indian remains a legal term. When searching for cases such as McGirt or related social science literature, it is important to include search terms such as Indian and tribal as alternates to Native American and nation.

A comprehensive topical literature review, akin to a legal nutshell, is another common way to present disciplinary principles and prior research. Many empirical researchers organize topical literature reviews in a funnel format, starting with general information and finishing with a specific and arguably understudied subtopic (Denney & Tewksbury, 2013). The topical literature review often concludes with the researcher’s hypotheses and/or research questions, which will help to expand the research on the understudied subtopic. Chronological and comprehensive topical literature reviews read more neutrally than a third type of social science literature reviews: the debate type.

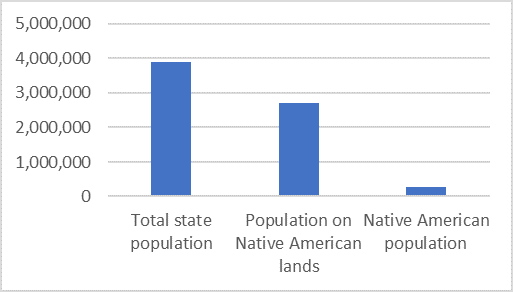

Debate is a third format for empirical literature reviews. Many debate-style literature reviews will feature two broad camps or perspectives (e.g., Ares & Varela, 2017). Some authors will showcase the strengths and weaknesses of both sides (e.g., Ares & Varela, 2017) while others will advocate for one side (e.g., Bennett, Maton, & Kervin). The latter style is less common in the social sciences but closer to persuasive law review format (e.g., Ryan, 2020). Some debate-style articles concern primary source documents such as jurisdictional boundary maps (e.g., as related to the McGirt case, see Spears, 2022) and contested statistics such as racial, ethnic, or group population totals.

3.2 Map of Native American national lands in Oklahoma. (Oklahoma Department of Transportation)

3.3 Oklahoma population estimate comparisons. (Total state population: 3.9 million residents; total population on Native American lands: 2.7 million residents; Native American population: 266,000). 2016-2020 ACS 5-year estimates (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020).

A fourth format for empirical literature reviews is an agenda setting format. Agenda setting articles analyze the strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in a field and recommend future research directions (e.g., Ryan, 2014). Agenda setting articles tell scholars what they should be researching. While law students might set agendas in their law review notes, junior social scientists rarely write agenda setting articles. But law professors, judges, and experienced attorneys can write them. Agenda setting articles require similar yet more exhaustive literature review research than comprehensive topical articles. In public health and other science-adjacent social sciences, agenda setting articles might include systematic reviews or meta- analyses that compare the methodologies, findings, and take-aways of multiple studies.

Regardless of the type of literature review selected, the patron’s write-up should be well-organized. Early in the research process, patrons should be able to articulate a rough outline for their research and writing, including a main thesis and sub-topics (Figure 3.4). This outlining should be nearly impossible for patrons if they have yet to read literature on the topic. Law librarians should dissuade patrons from guessing at subtopics and instead demonstrate how groundwork research—of even a few articles on the topic—can indicate important subtopics.

3.4 Typical literature review outline

Thesis statement

Introduction

Literature Review

Sub-Point 1

Summary statement

Evidence (research articles, existing data, etc.)

Evidence (research articles, existing data, etc.)

Transition/connection to next main point

Sub-Point 2

Summary statement

Evidence (research articles, existing data, etc.)

Evidence (research articles, existing data, etc.)

Transition/connection to next main point

Sub-Point 3

Summary statement

Evidence (research articles, existing data, etc.)

Evidence (research articles, existing data, etc.)

Hypotheses, research questions, and/or transition to methodology section, etc.

The law librarian can offer this early outlining advice in three parts. First, librarians can ask patrons to describe high-level themes, research areas, fields, etc. associated with the topic. On a white board or piece of paper, the librarian can depict each theme as a circle and draw a Venn diagram of interrelated academic fields and research themes. Second, the librarian can drill down on relevant disciplines, databases, and journals for one or more of the themes. Third, the librarian can demonstrate how to find relevant research guides, construct a search, and retrieve articles. If the patron is pressed for time, the librarian can run a quick search in a broad search engine such as Google Scholar and ask the patron to identify which results are more or less useful. Even if the patron leaves quickly after that search, it will likely have spurred some useful insights. These initial discoveries are important for the next phase of literature review research: comprehensive database searching.

3.5 Notes from the Desk of Sarah E. Ryan: My special purpose districts work

One of my most rewarding projects as an empirical legal research librarian was helping a patron compile a comprehensive library of more than 125 social science articles on special purpose districts (SPDs). Special purpose districts are governmental or quasi-governmental entities with “a structural form, an official name, perpetual succession, and the rights to sue and be sued, to make contracts, and to obtain and dispose of property” (Bollens, 1957, p. 1). Special Purpose Districts perform public services separate from, in addition to, or in conjunction with the government. For instance, the businesses in Times Square contribute to a business improvement district that provides cleaning and security services to that section of Manhattan above and beyond what New York City could provide (Gopal-Agge & Hoyt, 2019; Mitchell, 2009). Some SPDs are created or enable by legislation, such as the Air Pollution Control Districts Act of Washington State (Ryan, 2016).

Building a comprehensive SPD literature review was difficult because SPDs are born out of economic, historical, and political necessities (Foster, 1997) and researched by scholars in various disciplines. The U.S. experiment with SPDs has spurred law school symposia (e.g., Dilworth, 2010; Ryan & Saunders, 2004) and international research (e.g., Roost, 2013). As a result, empirical researchers should search a range of databases, some international.

To improve my chances of finding as many SPD articles as possible, I searched various databases, including EBSCOhost/Academic Search Complete, Google Scholar, and Web of Science/Web of Knowledge. I also skimmed titles and abstracts to learn about the subject material. I quickly learned that special purpose districts can be named according to their purpose and/or location. Airport districts can be SPDs, though they do not always meet the criteria of being self-contained entities with quasi-governmental or organizational powers. So, I started including airport as a search term.

To keep track of my research and assist my patron down the road, I created a citations spreadsheet in Excel. I wrote code to read the last name of the first author and year of publication into separate columns. Citation managers such as RefWorks and Zotero can offer similar utilities, but librarians need to verify that their patrons are willing to work with those systems.

In addition to the literature review, I helped my patron build a master list of SPDs. I used directories and government data collections as sampling frames (see Chapter 3) to find SPDs. Directories included the Governments Master Address File (GMAF) and the Governments Integrated Directory (GID, for older data). Data collections included the U.S. Census Bureau’s Census of Governments (COG) and Annual Survey of State Government Finances (ASSGF). Today, the Census Bureau offers a number of additional Census of Government data tools online.

In the end, my SPD research was much appreciated by my patron, and I learned that there are quasi-governmental entities operating all around me and fueling research around the globe.

Databases, Journals, and Authors

Researchers can find articles via many paths, including databases, journals, and known authors. Law students often need assistance in starting down these paths. For decades, students have trained on two primary databases: Lexis and Westlaw. Now, students train on a host of newer platforms, including Bloomberg Law and Fastcase. But few receive graduate training on social science research platforms and databases. As a result, law librarians often need to assist law students and legal professionals in finding and using social science research tools such as databases, research association and journal websites, and author pages.

The fastest way to find a database in an unfamiliar empirical area is to locate research guides written by university librarians serving that area. An Internet search for “political science research guide” yields more than 20 pages of university guides, for instance. Each guide should include broad databases, such as Web of Science/Web of Knowledge, and disciplinary databases, such as Worldwide Political Science Abstracts. Because legal researchers will be accustomed to certain search operators and wildcards, law librarians should orient them to the reference guides and training materials for social science databases, which should include lists of operators and symbols. For instance, Web of Science recognizes the Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT, contains a NEAR/n operator where n is the number of words between search terms (Georgia NEAR/3 wheat), and permits three wildcards: *, ?, and $ (Clarivate/Web of Science, 2021). EBSCOHost uses slightly different wildcards: *, #, and ? (EBSCO, 2021). Of course, there are many free databases such as SSRN , which links to nearly one million draft and published research papers.

3.6 Guided questions for literature review co-searching with a patron

1. What bodies of knowledge are connected to your topic, broadly and specifically (e.g., Political Economy, ecofeminism, Rwandan history)?

2. Which databases might cover these domains or your subject matter?

___ Google Scholar (broad, interdisciplinary)

___ EBSCO (broad, Humanities, Soc. Sci.)

___ JSTOR (Humanities, History, Soc. Sci.)

___ ProQuest Congressional/Legislative Insight (Legal History)

___ Web of Science (Science, Soc. Sci.)

___ Westlaw/Lexis (Law, News)

___ Other:

3. Which keywords and search terms might yield the documents you’re seeking? (e.g., sentencing, exports, military sexual trauma, colonization)

4. (After finding 1-2 relevant articles): Which additional search terms do the titles and abstracts of these articles suggest for your search?

Once patrons have a few databases to search, law librarians can help them identify relevant academic journals. In the social sciences, flagship journals are often sponsored by the discipline’s national scholarly association. An Internet search of the discipline and the word association (e.g., Communication AND association) will often yield the national scholarly association as one the first few results (e.g., National Communication Association for U.S. Communication scholars). Most association websites will feature a publications or journals page listing the sponsored journals. Of course, effective database searching should yield articles from some of these journals. But as we know, pursuing different pathways is the key to building a comprehensive bibliography. Law librarians can encourage patrons to search in a database until they become satisfied or frustrated and then move on to an association’s relevant journals. A third strategy is to search author pages.

Most social scientists create research programs spanning years and publish multiple journal articles on single topics. While database and journal website results can suggest key authors, so too can internet searching. For instance, the search string “librarian censorship professor” yields news articles and professional websites of iSchool professors writing about censorship. A search for “professor tribal Oklahoma” yields results featuring experts on Native American tribal jurisdiction in Oklahoma and professors at tribal colleges in Oklahoma, a group of researchers that might not have occurred to the patron but will occur to law librarians, including Timothy Gatton, Associate Director for Research and Instruction at the Chickasaw Nation Law Library in Oklahoma.

3.7 Law Librarian Spotlight: Timothy Gatton

As the Associate Director for Research and Instruction at the Chickasaw Nation Law Library, Timothy Gatton provides numerous services for Oklahoma City University School of Law students. His courses include Oklahoma Legal Research and Texas Legal Research, among others. Mr. Gatton serves as a faculty advisor and mentor for students preparing for the bar exam. He also sponsors and assists students with their law review articles, or notes (Moyer, 2021). He finds that one of the most rewarding aspects of his job is that the student he is teaching today could become a future Oklahoma Supreme Court justice. In addition to working with students, Mr. Gatton’s role includes collection development and the regular updating of the library’s LibGuides, a collection of over fifty legal resource guides. These guides cover a wide range of topics from immigration law and veterans benefits research to English legal history and fact-finding on the Internet. Like many law librarians, Mr. Gatton is a career-changer. At the age of 43, he began law school at the Oklahoma City University School of Law. He found his favorite course was legal research and that began his path toward a career in law librarianship. After completing his law degree in 2010, Mr. Gatton obtained his M.L.I.S. from the University of Pittsburgh before returning to accept a position with the Oklahoma City University School of Law, Chickasaw Nation Law Library. (Gatton, 2022).

Resource Evaluation

Law students learn to appreciate the differences among law review articles, legal research monographs, textbooks, hornbooks, and study materials. They develop a gut sense of which legal resources are more rigorous, high-quality, and/or useful for the current research issue. Social scientists carry their own set of assumptions for evaluating resources.

The primary social science assumption is that peer-reviewed resources are more rigorous than non-peer reviewed resources. Law librarians should educate non-social scientists about what peer review is and which resources tend to be peer reviewed.

3.8 Overview of the peer review process

Most social science peer review proceeds in six or fewer steps. First, an author submits an article manuscript to a single journal. Second, an editor skims it to ensure that it meets baseline standards for quality and falls within the subject area and goals—or scope and aims—of the journal. If the editor is satisfied, the article is sent to several peer reviewers. Peer reviewers tend to hold doctoral degrees, though some journals allow doctoral students and others to serve as peer reviewers. Third, the peer reviewers independently review a blinded copy of the manuscript in which all author information has been removed. They each vote on whether the article should be accepted or rejected. Most journals have a range of accept/reject options such as: accept, minor revisions, revise and resubmit (i.e., neither acceptance nor rejection), and reject. Fourth, the editor collects two or more reviews and decides whether the manuscript should be rejected or continue in the process (e.g., acceptance or revise/resubmit). The editor communicates this information to the author. Fifth, in the case of a revise and resubmit determination, the author may make improvements to the manuscript and submit it for a second round of peer review. Sixth, for all articles that reach the acceptance stage, the editorial team works with the author on technical corrections and the article appears in print. The process takes many months and sometimes years. Almost no social science journals employ cite-checking, like law reviews, or fact-checking, like major newspapers.

Once a patron understands what peer review is, the law librarian should indicate which social science materials tend to be peer-reviewed.

Most books are not peer-reviewed, nor are magazines, newspapers, reports, websites, and of course, most law reviews, which are cite-checked—law students retrieve the cited material and check paraphrases, quotations, and facts for accuracy––but not peer reviewed. Most social science journals are peer-reviewed but not cite-checked.

|

|

Cite/fact checked? |

Peer reviewed? |

Editor reviewed? |

|

Peer-reviewed academic journal |

Rarely |

Always |

Always |

|

Academic book |

Rarely |

Rarely |

Always |

|

Law review (journal) |

Always |

Rarely |

Always |

|

Newspaper article |

Sometimes |

Rarely |

Always |

|

Magazine article |

Sometimes |

Rarely |

Always |

3.9 Review by publication type

An academic journal’s website should indicate that it is peer-reviewed. Researchers can verify this information using the Ulrichs database. This double check can be important. Just like in law librarianship, where bar journals and magazines can report research (e.g., AALL Spectrum), social science associations can publish magazines and newsletters that discuss research but are not peer-reviewed. For instance, Spectra is the National Communication Association’s non-peer-reviewed magazine whereas Review of Communication is one of the association’s peer-reviewed journals. Ulrichs contains entries for both of these publications and notes that the former is not peer-reviewed while the latter is. As law librarians show patrons Ulrichs it is important to note one confusing database feature: refereed means peer-reviewed whereas reviewed means that certain librarians have reviewed the resource. Even if Ulrichs lists a source as refereed, or peer reviewed, that does not mean that the research community will consider it an authoritative source on a subject area.

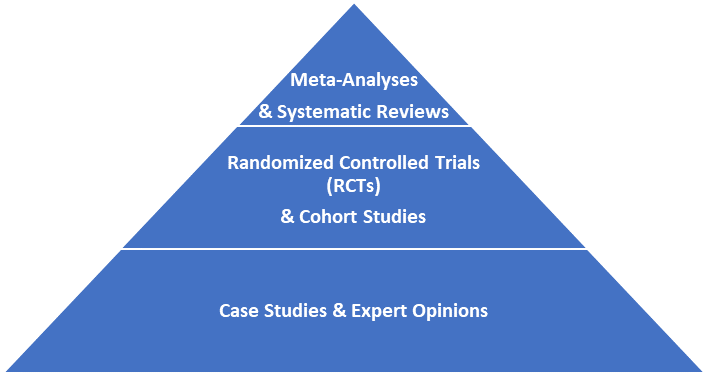

Peer review is a first sign of resource quality for social scientists, but there are many others. Like legal researchers, social scientists evaluate the age of the resource, the prestige of the journal, the qualifications of the author/researcher, and the quality of the argumentation. Beyond that, most public health and medical researchers, and some social scientists, place research in an evidence pyramid, or hierarchy in which single expert opinions (e.g., solo-authored article) and case studies are lower forms of evidence than resources that compare and contrast many studies, such as systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Librarians should explain that few law review articles are meta-analyses or systematic reviews. Even though legal scholars often discuss multiple cases, laws, research articles, etc., they do not make a side-by-side comparison of the methodologies, results, and take-aways from those resources.

3.10 Simplified evidence pyramid/hierarchy

Once legal patrons understand how social scientists evaluate evidence, they can review their initial outlines and groundwork research to discern gaps that require further research.

Reflection Questions

- Prior to reading this chapter, what was your impression of the similarities and differences between law review articles and social science articles? Has that changed? If so, how? If not, which facts or ideas in this chapter reinforced your existing beliefs?

- Would you feel competent to help someone create a social science article outline? If yes, where did you acquire outlining skills? If no or not yet, how could you gain additional outlining skills?

- What databases have you used to find social science research? Do you have favorites? Are there databases you have been hoping to try?

- In your opinion, what are the pros and cons of locating research along an evidence pyramid? What biases could the evidence pyramid introduce into resource selection and research writing?

References

Ares, G., & Varela, P. (2017). Trained vs. consumer panels for analytical testing: Fueling a long lasting debate in the field. Food Quality and Preference, 61, 79-86.

Arias-Londoño, A., Montoya, O. D., & Grisales-Noreña, L. F. (2020). A chronological literature review of electric vehicle interactions with power distribution systems. Energies, 13(11).

Bennett, S., Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(5), 775-86.

Clarivate/Web of Science. (2021). Web of Science core collection reference guide. Clarivate.

Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 24(2), 218-34.

Dilworth, R. (2010). Business improvement districts and the evolution of urban governance. Drexel Law Review, 3(1), 1-9.

EBSCO. (2021). Searching with wildcards in EDS and EBSCOhost. EBSCO Connect. https://connect.ebsco.com/s/article/Searching-with-Wildcards-in-EDS-and-EBSCOhost?language=en_US

Foster, K. A. (1997). The political economy of special-purpose government. Georgetown University Press.

Gatton, T. (2022, June 13). Personal communication with Adrienne Kelish [attorney and law librarianship student and research assistant at the University of North Texas].

Gopal-Agge, D., & Hoyt, L. (2019). The BID model in Canada and the United States: The retail-revitalization nexus. In G. Morçöl, L. Hoyt, J. W. Meek, & U. Zimmerman (Eds.), Business improvement districts: Research, theories, and controversies (pp. 139-158). Routledge.

Major Crimes Act, 18 USC §1153(a).

McGirt v. Oklahoma, 140 S. Ct. 2452 (2020).

Mitchell, J. (2009). Business improvement districts and the shape of American cities. SUNY Press.

Moyer, C. (2021). An Oklahoma tribal employer’s guide to conducting business in the Tenth Circuit. Oklahoma City University Law Review, 45(2), 215-264.

Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 597 U.S. ___ (2022).

Roost, F. (2013). Die Disneyfizierung der Städte: Großprojekte der Entertainmentindustrie am Beispiel des New Yorker Times Square und der Siedlung Celebration in Florida (Vol. 13). Springer-Verlag.

Ryan, J. E., & Saunders, T. (2004). Foreword to symposium on school finance litigation: Emerging trends or new dead ends? Yale Law & Policy Review, 22(2), 463-480.

Ryan, S. E. (2014). Rethinking gender and identity in energy studies. Energy Research & Social Science, 1, 96-105.

Ryan, S. E. (2016). Local-federal definitional divides: Special purpose districts and the challenges of empirical government research. Jurisdocs.

Ryan, S. E. (2020). Judicial authority under the First Step Act: What Congress conferred through section 404. Loyola University of Chicago Law Journal, 52(3), 67-125.

Ryan, S., Behpour, S., Bonds, C., & Xiao, T. (under review). Dissonant reflections on a quarter-century of JIEL: Authorship, methods, geographies, and subjects.

Spears, N. M. (2022, March 11). Oklahoma, tribes clash over jurisdiction after Supreme Court’s McGirt decision. Cronkite News [Arizona PBS], https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2022/03/11/oklahoma-tribes-clash-over-jurisdiction-supreme-courts-mcgirt-decision/

Williston, S. (1888). History of the law of business corporations before 1800. Harvard Law Review, 2(3), 105-24.