6 Assisting Patrons with Qualitative Research

Qualitative research requires patrons to make choices. Each decision charts a course for the remainder of the research. Law librarians can assist patrons in making informed choices during the formulation, design, execution, and reporting of qualitative research. Little of this assistance necessitates an advanced degree in a qualitatively-focused discipline such as Anthropology or Social Work. Rather, law librarians should guide patrons to the terminology and tools that they will need to conduct good research.

Qualitative methods vary from observations to interviews to shared community projects (see Chapter 4 for definitions; DeCarlo, Cummings, & Agnelli, 2021). Each research project requires different resources, but all qualitative research involves questions of whether the subject matter is studiable, what information to collect, and how to collect, manage, analyze, and report the information (social) scientifically. Law librarians can help patrons navigate these questions. But first, law librarians must teach some patrons that qualitative inquiry counts as empirical legal research.

Chapter learning objectives

- Describe examples of qualitative empirical legal research

- Ask questions to determine if qualitative research is the best approach for a project

- Understand unit of analysis, instrument/collection procedure, validity, and reliability

- Discuss the factors that drive research costs and complexity

Abbreviations and specialized terms

American Association of Law Libraries (AALL), Conference on Empirical Legal Studies (CELS), content analysis, corpus data management, data lifecycle, emergent research design, Foreign, Comparative & International Law (FCIL), information collection instrument/procedures, intercoder agreement/reliability, interrater agreement/reliability, interviewing, I.R.B., Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (JELS), Law & Social Inquiry, MAXQDA, NVivo, observational research, participant engagement, population, purposeful selection, reliability, sample, Society for Empirical Legal Studies (SELS), thematic analysis, thick description, triangulated methods, unit of analysis, validity

Can Qualitative Research Count as Empirical Legal Research?

Empirical legal researchers use a variety of methods to study law, government, and justice, some qualitative, some quantitative, and some descriptive. Due to the longstanding influence of Economics (see Chapter 1), the field is heavily dominated by quantitative research. But, journals such as Law & Social Inquiry publish diverse qualitative work, and the best legal empiricists remain open to qualitative and mixed methods research, as the work of Theodore (Ted) Eisenberg demonstrates.

First, empirical legal researchers conduct qualitative and multimethodological research, as articles from Law & Social Inquiry demonstrate. In a 2016 article, professors Sumner and Sexton studied the perceived safety and security of transgender inmates. Through interviews and focus groups with inmates and focus groups with prison staff in four facilities, the researchers found that “sex segregation [wa]s so fundamental to . . . prison operations” that transgender inmates faced safety issues before they even arrived at their facilities (Sumner and Sexton, p. 637). Further, the prison staff involved in the study seemed fixated on transgender inmates’ sexual orientations and on managing their sexual behaviors (Sumner and Sexton). Transgender inmates reported that they were differently punished than other inmates and wanted similar autonomy as their peers (Sumner and Sexton). The Sumner and Sexton study incorporated traditional qualitative research traditions such as open-ended questions, reporting responses as text, and providing thick descriptions of individuals’ ideas via lengthy direct quotes.

In 2018, Law & Social Inquiry published an issue on visual information and the law that brought qualitative and quantitative researchers into conversation. In the first article, doctoral candidate Anna Banchik descriptively analyzed briefs filed in the ACLU v. DoD cases, in which the ACLU argued that the Department of Defense (DoD) should release photos of post-9/11 detainee abuse in Iraq and Afghanistan (2018). In response, numerous federal agencies claimed that the photo releases would endanger lives and national security (2018). In the second article in the issue, professor Jay Aronson demonstrated how Carnegie Mellon researchers were deploying a machine learning system called E-LAMP (“Event Labeling through Analytic”) to detect violent acts and weaponry in photos and video, including mortar launchers in audiovisual content from Aleppo, Syria circa late 2013. The goal of the article was to increase conversation among researchers and human rights practitioners in order to “level the playing field between the human rights community and the entities that perpetrate, tolerate, or seek to cover up violations” (Aronson, 2018, p. 1188). Later in the special issue, professor Mary Fan analyzed the body camera policies of fifty-nine police departments (2018). Professor Fan reported both summary statistics and narrative extracts from a half-dozen policies (2018). Her research showed that departmental data policies varied but were focused on retention of the evidence needed for prosecution of individual cases rather than for other purposes, such as evidence for citizens’ civil suits against the police (Fan, 2018). The Law & Social Inquiry special issue covered legal topics ranging from individual privacy to criminal exoneration to political violence (Brayne, Levy, & Newall, 2018). It also showcased the journal as a venue for qualitative empirical legal research, which is increasingly conducted with the aid of narrative analysis software.

In 2022, Levesque and colleagues analyzed 301 reports from volunteers trained by the Human Rights Defender Project to observe immigration court hearings. The team used NVivo software to conduct multiple rounds of text searching for words and phrases such as “‘crime,’ ‘aggravated felony,’ [and] ‘moral turpitude’” (Levesque et al., p. 12). The researchers reported dozens of short snippets from observers’ notes and several longer snippets (Levesque et al.). They found that three narratives, or heuristics, predominated immigration hearings: threat, deservingness, and impossibility (Levesque et al., p. 22). Levesque and colleagues’ research showed that to prevail in immigration court, detainees must tell a story that seems personal, unique, heuristically-valid, convincing, and within the bounds of specific legal criteria (Levesque et al.). In conjunction with Levesque’s article, the journal published the information collection instrument—Human Rights Defender Project: Court Observation Form—as a supplementary file on its website. These examples suggest that Law & Social Inquiry is a venue for qualitative legal research and that qualitative studies are a valid form of evidence-driven legal research. In a similar vein, renowned quantitative legal researcher Ted Eisenberg demonstrated appreciation for qualitative methods in his work.

For decades, professor Eisenberg was a leading empirical legal research scholar. He co-founded the Society for Empirical Legal Studies (SELS), Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (JELS), and Conference on Empirical Legal Studies (CELS) (Heise, 2014; Ramello & Voigt, 2020). He encouraged generations of researchers to start with data, follow that data, and tell people what the data said (Heise, 2014; Ramello & Voigt, 2020). Almost all of professor Eisenberg’s work was quantitative, including more than a dozen articles in JELS, and dozens outside of JELS on judges, juries, and bankruptcy law. But despite his skill and focus on quantitative research, professor Eisenberg understood that some questions required qualitative, or at least triangulated, answers.

In the late 1990s, professor Eisenberg wanted to know “What makes jurors think a defendant is remorseful?” (Eisenberg, Garvey, & Wells, 1997-1998, p. 1600). Existing research could not answer that question because it relied on data from the general population, written material from cases, or case studies of particular trials (Eisenberg, Garvey, & Wells). No legal researchers had “systematically gathered data from jurors who served on capital cases” (Eisenberg, Garvey, & Wells, p. 1601). Professor Eisenberg’s team interviewed jurors in cases that resulted in 22 death sentences and 19 life sentences in South Carolina (Eisenberg, Garvey, & Wells). The researchers found crime-related, defendant-related, and juror-related influences on jurors’ appraisal of remorse, including whether the defendant looked bored during the trial (Eisenberg, Garvey, & Wells). The team’s approach was methodologically atypical for qualitative research because they used many closed questions, reduced most responses to data points, and performed a factor analysis. Still, the remorse study centered around interviews, allowed jurors to dictate some of the findings, and demonstrated an important role of qualitative—or mixed methods—research: to fill gaps and lay the foundation for further research. Later on, the remorse study was cited by researchers conducting traditional qualitative research (Angioli & Kaplan, 2017), including semi-structured interviews and thick description of prosecutor decision-making and probation officer perceptions of remorse during the presentence report writing phase of sentencing (Berryessa, 2021). Professor Eisenberg’s foray into interviewing is but one example of qualitative empirical legal research. But just because research can be qualitative, that does not mean that it should be qualitative.

6.1 Law Librarian Spotlight: Dan Wade

While Ted Eisenberg was encouraging legal researchers to follow the data, Dan Wade was advising law librarians to open a book (Rumsey, Allison, & Raisch, 2020). For more than 40 years, Mr. Wade ensured that foreign, comparative, and international law (FCIL) books and materials were available for research (Shapiro et al., 2021). He helped build the Mexican law collection at the University of Houston and a renowned African law collection at Yale Law School that yielded countless qualitative studies (see Ryan, 2013). He helped launch the Foreign, Comparative, and International Law Special Interest Section (FCIL-SIS) of the American Association for Law Libraries (AALL), and mentored countless FCIL librarians (Rumsey, Allison, & Raisch). Mr. Wade encouraged larger law libraries to work together to collect FCIL materials for present and future researchers (Shapiro et al.). He advised smaller law libraries to engage their communities when deciding what to collect (Shapiro et al.). He connected FCIL collecting to broader social issues, and founded a human rights book club for law librarians (Rumsey, Allison, & Raisch).

Should the Research be Qualitative?

When newer researchers approach law librarians for assistance with early-stage research, we can help them make threshold decisions such as whether the work should be qualitative, quantitative, or both (i.e., mixed methods research, triangulated research). To determine if research should be qualitative, law librarians can first ask: Are you open to inductive inquiry, or letting the participants or information reveal patterns, themes, and truths? In qualitative inquiry, researchers remain open to emergent meaning (Braun, Clarke, & Gray, 2017; Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

For human subjects research, law librarians should ask: Are you willing to engage your participants and let them drive the research? Qualitative researchers rarely interact with their subjects in laboratories or neutral spaces. Instead, they go to where the subjects are—courthouses, prisons, schools—so that they can engage them in context (Creswell & Creswell). Further, qualitative researchers privilege participants’ understandings, including what key research terms mean. While qualitative researchers start with a broad understanding of the research phenomenon—such as intergroup trust—the participants dictate how the phenomenon plays out in practice.

Third, law librarians should ask: Can you study the subject by qualitative methods? Interesting phenomena can be qualitatively unresearchable for a host of reasons. First, insufficient data could exist because the phenomenon is too new or a set of community practices has yet to develop or the data is closely safeguarded by participants, etc. Second, the researcher can be the wrong person to conduct the inquiry because participants will not trust or communicate with her, because she is not in a position to understand the participants’ perspectives, or because she is not flexible enough to allow participant control of the research. Third, other actors such as funding or supervisory agencies can demand quantitative rather than qualitative data.

Fourth, law librarians should ask: Is a qualitative approach better than the alternatives? Qualitative research is a good choice when researchers want to understand issues, problems, and lived experiences holistically. By contrast, quantitative research is a good choice when researchers want to control the research variables and participants’ possible choices, experiences, or answers. Quantitative research is best when researchers want to reduce complicated phenomenon to numbers (Jenkins-Smith et al., 2017). Triangulated, or mixed-methods studies involving qualitative and quantitative techniques are optimal when researchers want to both reduce a phenomenon to numbers and also understand the complex human experiences driving those numbers.

What Information Should I Collect?

Qualitative researchers tend to think of the information they collect in broader terms than data. Participants can provide information in the form of answers, artifacts, bodily movements, drawings, songs, stories, tweets, and more. This broad definition of research information can overwhelm newer researchers. Law librarians can help these patrons navigate a series of terms, research practices, and decisions about what qualitative information to collect. This conversation should start with a review of the researcher’s topic or research question, which should identify people, places, issues, etc. The patron can use the topic statement or research question to articulate the unit of analysis, population, and study site(s).

Complex legal phenomena can be studied from a variety of angles. The role of governments in facilitating inter-group violence, for instance, can be research at the individual level (e.g., dictator), small group or organizational levels (e.g., government-backed militias and hate groups), and societal level (e.g., legal frameworks for citizenship, hate crimes). Social scientists call these levels “units of analysis” (see Bhattacherjee, 2012).

Once a patron decides on the unit of analysis, that decision can help answer who, what, when, where, and how questions. For instance, if the researcher wants to understand the personal experiences of Japanese-Americans following World War II, he should determine if he is interested in citizens living—and likely interned—during the war, born after the war, or both. He should think about whether he wants to collect information from individuals, families, or groups. He should determine if geography matters, for instance the experiences of Japanese-Americans living on the west coast or elsewhere. After thinking through these and other possibilities, the researcher can determine who his research participants should be, what information he would like to gather from them, where they are likely to be located, and how he might approach and engage this population.

Most research questions will indicate a specific population, such as Japanese-American individuals interned in the United States during World War II. Populations can be people, institutions, and even document collections (e.g., the Japanese American Internees records held by The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration). Few researchers aim to collect evidence from entire populations. Rather, researchers gather data from a subset of the studied people, documents, etc. While quantitative researchers strive to use a sampling frame and employ random sampling (see Chapter 5), qualitative researchers focus on purposefully choosing research participants, documents, sites, etc. (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Purposeful selection focuses on who will participate in the research, where the research will happen, what will be gathered, and how the process should unfold (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Because qualitative researchers view themselves as active information gatherers and/or research co-participants (Creswell & Creswell), they consider their standpoints when selecting their research subjects and sites. In human studies research, qualitative researchers must be able to enter the communities they wish to engage. The researchers’ identities—gender, race, religion, nationality, etc.—can pose barriers to access and dialogue.

6.2 Access and engagement strategies in Ahmed’s research on Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh

Rushdia Ahmed and her research team faced challenges when trying to engage Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh in discussions of sexual abuse and sexual and reproductive health services (Ahmed, et al., 2020). Most of the refugees considered the research topic taboo. Many had been traumatized and forcibly displaced. Their legal status in Bangladesh was politically sensitive. They lived in loosely organized, overcrowded hillside camps with no addresses. No master list of the refugees existed. In response to these challenges, the research team employed a flexible approach to information gathering. For instance, they used random sampling of camps not of individuals (i.e., since a sampling frame for individuals did not exist). They reserved questions about abortion and family planning for married girls and women. They paired male information collectors with male participants and enlisted Majhiis, or Rohingya camp leaders, to help them recruit participants and understand the specific context of each camp. These strategies enabled the team to gather information from a vulnerable group in emerging community settings.

While purposeful selection is more flexible than most quantitative sampling approaches, qualitative researchers strive to collect information that is sufficient to answer their research questions and representative of the people or communities they are studying. Qualitative researchers think critically about instrument design or information collection procedures, validity, and reliability.

How Should I Collect Information?

For qualitative researchers, instrument design or information collection procedures are foundational study design considerations. Qualitative researchers often witness the time and effort participants contribute to the research. As a result, they carefully plan how they will collect information before engaging research participants or their artifacts. Law librarians can help patrons understand how qualitative researchers plan information collection and assess the validity and reliability of their research.

Discussing the Instrument or Information Collection Procedures

A research instrument is an information collection tool (see Chapter 4 for examples). Common qualitative instruments include video and audio recorders for interview and focus group research and coding sheets for document analysis (i.e., sheets that allow coders to record attributes of the document, such as judge name; see Saldaña, 2021). Less common instruments include photo cameras, which participants can use to document the world around them (see Freire, 2005), and drawing tools, which individuals can use to sketch their ideas and answers to questions (see Singhal & Rattine-Flaherty, 2006). Newer instruments include blogs, tweets, and other public and private born-digital content (see Braun, Clarke, & Gray, 2017). In highly-emergent qualitative studies, the researchers will not develop an instrument in advance but will instead articulate broad rules or procedures for participant engagement. In determining how to collect information, researchers should answer two questions: 1) Where is the information located? and 2) How do I want to engage with it and/or the research participants?

First, researchers should determine where the information is or will be located. Information can be in human minds, diaries, daily rituals, dwellings, etc. Information can be in audio, print, or visual media. Information can emerge during group processes, such as legislative hearings. Researchers must determine if the information currently exists or will be created and where it is or will be located (e.g., future, un-transcribed housing court hearings).

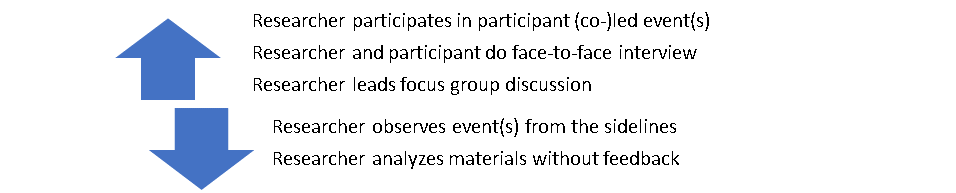

Second, researchers should decide how they want to engage with the information and participants. Engagement can be conceived as a continuum from most to least researcher-participant interaction or shared meaning-making. Arguably, the most engaged information collection technique involves a researcher actively participating in an event, ritual, or ceremony (co-)led by participants. By contrast, the least engaged technique involves a researcher reviewing documents without feedback from the people that created them.

6.3 Examples of higher and lower engagement during qualitative research information gathering

Within every qualitative methodology—e.g., observations, interviewing, content analysis, mixed methods and case studies—researchers can elect to be more or less engaged. For instance, researchers can conduct interviews face-to-face, a highly sensory experience that requires continual verbal and nonverbal engagement. Or, they can eliminate visual information via telephone interviewing, or audio/visual information via electronic mail interviewing (Creswell & Cresswell, 2018). Researchers can hire people to conduct interviews for them, particularly when the researchers face language barriers with their participants. These intermediaries can be instrumental to securing access and building trust with the research participants (see Ahmed, et al., 2020). Still, the use of intermediaries generally means a loss of researcher-participant interaction, engagement, and shared meaning. This information loss can undermine validity and reliability.

Discussing Validity and Reliability

Broadly, validity asks “Does the research measure what it is supposed to measure?,” whereas reliability asks “Would this research process produce similar results if repeated?” Qualitative researchers employ a number of techniques to increase the validity and reliability of their work.

Qualitative researchers characterize validity as authenticity, credibility or trustworthiness (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). A researcher’s conclusions about the routine behaviors of a certain group, such as the work of career judicial clerks, should authentically represent the group’s typical actions. By contrast, a description of an unusual or atypical event, like a clerk’s retirement party, would be an invalid portrayal of how the group usually acts (e.g., parties and farewell speeches). Qualitative researchers use seven techniques to increase validity: 1) identifying and describing researcher biases, 2) employing triangulated methods, 3) spending ample time with participants, 4) asking participants to validate each other’s accounts (i.e., peer debriefing) and/or the researcher’s findings, 5) using direct quotes and detailed, or thick, descriptions of the collected information, 6) including aberrant, discrepant, or negative information, and 7) asking external auditors, coders, or reviewers to evaluate the research (i.e., prior to submitting it for academic peer review) (Creswell & Creswell).

Qualitative researchers characterize reliability as research process consistency, transparency, and thoroughness. Because qualitative research is more flexible and emergent than quantitative research, it need not be as procedurally replicable. Future researchers cannot interview the research subjects on the same days as prior researchers did, for instance, and could receive different answers due to the passage of time (e.g., attitude change, memory shift/loss). Still, social scientists strive to develop processes that could be reliably followed by others. Qualitative researchers use six techniques to increase reliability: 1) documenting study design decisions and research protocols, 2) scheduling routine meetings with the research team, 3) employing neutral coders, interviewers, or other research information collectors, 4) comparing agreement among information collectors tasked with numerical or thematic analysis work (i.e., intercoder or interrater agreement/reliability), 5) checking and correcting the work of all information collectors, and 6) using software tools, existing research instruments, and other outside resources as reliability cross-checks (see Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

How Should I Manage Research Information?

Qualitative research information has a lifecycle similar to quantitative data (see Chapter 5). Librarians should discuss the basics of information management with their patrons, including information acquisition, storage, cleaning, and preservation. Law librarians can teach patrons about the data lifecycle and encourage them to think about how they will manage their information throughout the research, including after the research ends. Due to the humanistic nature of qualitative inquiries, researchers must often manage their participants’ personal and identifiable information, such as transcripts of interviews conducted with detainees or incarcerated people. Prior to information collection, researchers should decide how they will collect, protect, and preserve this information in a way that shields participants’ privacy and honors their participation in the research. To protect privacy, researchers should control notes and instruments during information collection and store them in safe places after collection (e.g., locked cabinets, password-protected computer files). Some researchers also use pseudonyms and other techniques to shield individuals’ identities. To honor participants’ contributions, researchers should retain research information—often for years—to facilitate further research or participant check-ins. Document-based qualitative research involves a range of privacy and preservation concerns because researchers can collect public, quasi-public, and/or private documents. Human subjects research typically needs I.R.B., or research ethics board, approval. These boards require researchers to explain their data protection and preservation policies. Just as a data lifecycle conversation can encourage researchers to explicate their short and long-term plans, so too can a budgeting discussion.

Second, law librarians can discuss research budgeting with their patrons. These conversations can help patrons understand the costs of information collection and management. For example, three common factors seem to drive corpus research costs: material origin, retrieval method, and analysis type (Ryan, Rashid, & Ali). In general, born-digital materials are less expensive to manage than print materials that need to be digitized. Scrapable web-based materials require less research assistant time than digital materials stored as PDFs or print materials (Ryan, Rashid, & Ali). Hand-coding is often more expensive than automated analysis using machine learning approaches (Ryan, Rashid, & Ali). The point is: corpus data research, like every type of qualitative research, can be performed in a more or less costly manner. Cost conversations can help patrons to strategize and economize information gathering, cleaning, analysis, reporting, and other costs.

6.4 Notes from the Desk of Sarah E. Ryan: Understanding Project Costing via the Dutch Letters Project

In 2021-22, I worked with two doctoral student researchers—Mohotarema Rashid and Irhamni (Ali)—to determine the factors driving the costs and likelihood of grant-funding of corpus projects. We reviewed interdisciplinary research articles and project websites, analyzed U.S. government grant datasets, and dissected two of my recent corpus projects. One of the research projects we read about involved more than 1,000 boxes of Dutch documents, including 15,000 private letters confiscated by sailors from the 1650s-1830s (see Rutten & van der Wal, 2014). The letters project was mammoth. The researchers had to travel to another country to scan the documents. They had to train teams of transcriptionists. They had to invent a new method of identifying same authors across letters by their grammar and syntax choices. Of course, the project required a dedicated database and custom metadata. It was one of the most complex corpus research projects ever conducted. The project was grant-funded for more than half a decade and took many more years to complete. The team’s research uncovered writings and markings from lower class Dutch people who lived hundreds of years ago, when few of the world’s poor left any documentary evidence. The Dutch letters project write-ups, along with our other data, suggested that at least 14 factors drive resource needs and/or funding for corpus projects: (1) material origin, (2) retrieval method, (3) analysis type, (4) institution type (e.g., public or private university), (5) institution location, (6) institution name, (7) project alignment with broad funding agency priorities (e.g., preservation), (8) project alignment with narrow funding agency preferences (e.g., preservation of born-digital materials), (9) current project stage (e.g., sample frame identified), (10) availability of technical partners (e.g., machine learning experts), (11) willingness of vendors to sell needed data, (12) capacities and interests of research assistants, (13) availability of data storage, sharing, and/or dissemination infrastructure, and (14) flexibility and commitment of the lead researcher(s). Some of these factors drive costs and funding in other types of qualitative research.

How Should I Analyze and Report The Information?

Information analysis and reporting occur at the mid- and late-points of a qualitative research project. Most research methods textbooks discuss these research phases, as do empirical legal research articles, like the Law & Social Inquiry pieces discussed above. We can share this information with patrons as part of our scholarly communication work.

Qualitative analysis typically involves five steps. First, the researcher organizes the information, for instance by collecting all of the observers’ reports of the hearings they attended. Second, the researcher prepares the information for analysis. If using qualitative analysis software such as Nvivo or MAXQDA, the researcher automatically or manually inputs the information. Third, the researcher reviews the information for completeness and an early impression of the findings. Fourth, the researcher examines the data multiple times to identify themes, patterns, trends, and even discordant ideas. Fifth, the researcher begins to write about the findings and circles back to the data for correction, deeper meaning, and thick description excerpts and examples (see Creswell & Creswell, 2018). In qualitative research, late-stage analysis and reporting overlap and exist in conversation. Just as in the planning phase of the research, we can help patrons think through the steps of qualitative analysis and scholarly communication.

Reflection Questions

- Prior to reading this chapter, what was your understanding of reliability and validity in qualitative research? Has your understanding changed? If so, how? If not, which facts or ideas in this chapter reinforced your existing understanding?

- Do you have experience conducting research interviews? If yes, what lessons has this experience taught you? If no or not yet, how could you gain additional research interviewing skills?

- In general, have you found quantitative or qualitative research more useful in understanding the law and justice issues that most interest you?

- In your opinion, should law librarians help to promote the lesser-known qualitative side of empirical legal research? Why or why not?

References

Ahmed, R., et al. (2020). Challenges and strategies in conducting sexual and reproductive health research among Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Conflict and Health, 14(1), 1-8.

Angioli, S., & Kaplan, P. (2017). Some things are just better left as secrets: Non-transparency and prosecutorial decision making in the era of neoliberal punitivism. The Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice and Criminology, 5(1).

Aronson, J. D. (2018). Computer vision and machine learning for human rights video analysis: Case studies, possibilities, concerns, and limitations. Law & Social Inquiry, 43(4), 1188-1209.

Banchik, A. V. (2018). Too dangerous to disclose? FOIA, courtroom “visual theory,” and the legal battle over detainee abuse photographs. Law & Social Inquiry, 43(4), 1164-1187.

Berryessa, C. M. (2021). Modeling “remorse bias” in probation narratives: Examining social cognition and judgments of implicit violence during sentencing. Journal of Social Issues, 78(2), 452-482.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. Center for Open Education/University of Minnesota’s College of Education and Human Development. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/79

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Gray, D. (2017). Collecting qualitative data: A practical guide to textual, media and virtual techniques. Cambridge University Press.

Brayne, S., Levy, K., & Newell, B. C. (2018). Visual data and the law. Law & Social Inquiry, 43(4),1149-1163.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

DeCarlo, M., Cummings, C., & Agnelli, K. (2021). Graduate research methods in social work. https://pressbooks.rampages.us/msw-research/front-matter/downloads/

Eisenberg, T., Garvey, S. P., & Wells, M. T. (1997-1998). But was he sorry? The role of remorse in capital sentencing. Cornell Law Review, 83(6), 1599-1637.

Fan, M. D. (2018). Body cameras, big data, and police accountability. Law & Social Inquiry, 43(4), 1236-1256.

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed (50th Ann. ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Heise, M. (2014). Following the data and a giant: Remembering Ted Eisenberg. Cornell Law Review, 100(1), 8-11.

Jenkins-Smith, H. C., Ripberger, J. T., Copeland, G., Nowlin, M. C., Hughes, T., Fister, A. L., Wehde, W. (2017). Quantitative research methods for political science, public policy and public administration: 3rd Edition with applications in R. University of Oklahoma/OU University Libraries, https://shareok.org/handle/11244/52244

Levesque, C., DeWaard, J., Chan, L., McKenzie, M. G., Tsuchiya, K., Toles, O., Lange, A., Horner, K., Ryu, E., & Boyle, E. G. (2022). Crimmigrating narratives: Examining third-party observations of U.S. Detained Immigration Court. Law & Social Inquiry.

Ramello, G. B., & Voigt, S. (2020). Let the data tell their own story: A tribute to Ted Eisenberg. European Journal of Law and Economics, 49(1), 1-6.

Rumsey, M., Allison, J., & Raisch, M. (2020). In memoriam: Three tributes to Dan Wade. International Journal of Legal Information, 48(3), 105-109.

Rutten, G., & van der Wal, M. (2014). Letters as loot: A sociolinguistic approach to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Ryan, S. E. (2013). The challenges of researching African high court opinions: Ten lessons learned from a four-country retrievability survey. Legal Reference Services Quarterly, 32(4), 294-306.

Ryan, S. E., Rashid, M., & Ali, I. (under review). Data-driven empirical research costing: Using scholarly literature, open government data, and formative case studies to plan projects.

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

Shapiro, F. R., et al. (2021). Memorial: Daniel Lawrence Wade (1944-2020). Law Library Journal, 113(1), 79-96.

Singhal, A., & Rattine-Flaherty, E. (2006). Pencils and photos as tools of communicative research and praxis: Analyzing Minga Peru’s quest for social justice in the Amazon. International Communication Gazette, 68(4), 313-330.

Sumner, J., & Sexton, L. (2016). Same difference: The “dilemma of difference” and the incarceration of transgender prisoners. Law & Social Inquiry, 41(3), 616-642.