4 Legal Data, Statistics, Bibliometrics, & Original Data Collection Services

Law libraries provide a host of data services. Law librarians help patrons find statistics for litigation briefs, draft regulations, and research papers. Academic law librarians collect citation counts, assess the factors driving these counts, and recommend additional channels for scholarly communication. Librarians build internal, library datasets and create statistics for institutional reporting and inter-institutional benchmarking. Librarians assist patrons in generating original research data, including navigating university human subjects committees, or institutional review boards (I.R.B.s). Corporate and firm law librarians help patrons use data and statistics for competitive intelligence, or using data to increase an organization’s business advantage. Legal information professionals license data for individual projects and organization-wide use. Data and informatics work is a rich and growing specialty within law librarianship.

Law libraries provide a host of data services. Law librarians help patrons find statistics for litigation briefs, draft regulations, and research papers. Academic law librarians collect citation counts, assess the factors driving these counts, and recommend additional channels for scholarly communication. Librarians build internal, library datasets and create statistics for institutional reporting and inter-institutional benchmarking. Librarians assist patrons in generating original research data, including navigating university human subjects committees, or institutional review boards (I.R.B.s). Corporate and firm law librarians help patrons use data and statistics for competitive intelligence, or using data to increase an organization’s business advantage. Legal information professionals license data for individual projects and organization-wide use. Data and informatics work is a rich and growing specialty within law librarianship.

While data services are diverse, this chapter describes four common service areas: 1) Finding data and statistics; 2) Gathering bibliometrics and helping patrons understand citation counts; 3) Collecting and reporting internal, library data and statistics; and 4) Assisting patrons with original data collection.

Chapter learning objectives

- Develop strategies for finding data and statistics, including bibliometrics

- Understand and explain the factors driving citation counts

- Contribute to library data collection, analysis, and reporting

- Explain how researchers can better plan and execute original data collection

Abbreviations and specialized terms

ALLStAR, ALM Global LLC, Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), Association of Research Libraries (ARL), benchmarking, bibliometrics, citation counts, competitive intelligence, data lifecycle, human subjects research review, impact, impact factor, I.R.B., open data portal, ORCID iD, original research data, population, sample, significance, text and data mining (TDM) license, Tuskegee Syphilis Study, unit of analysis, U.S. News & World Report (USNWR)

Finding Data and Statistics

Law librarians help their patrons find data, statistics, and secondary statistical analysis (SSA), or writings that interpret statistics. Just as we are trusted to recommend treatises and loose-leaf publications, patrons have faith that we can find data on their topics. Law librarians can develop their data-finding skills by visiting data sites, employing data-finding questions, and learning data-purchasing processes.

First, law librarians can lay the foundation for data expertise by visiting data sites and empirical legal repositories. Monthly, law librarians can visit the U.S. government’s open data portal at data.gov. Quarterly, librarians can explore web-based government agency and nonprofit organization data and statistics repositories, such as the National Institute of Justice site, Bureau of Justice Statistics site, and National Conference of State Legislatures site. Librarians can then delve into sites that correspond with the predominant needs of their primary patrons, such as criminal justice data, economic trend data, or elections data. Routinely, law librarians can attend legal data vendor trainings, such as Bloomberg Law for corporate law data, UniCourt for case tracking and docket analytics, ALM for firm, hiring, and legal industry analytics, TRACfed for administrative agency and government employee data, etc. Librarians can find additional data sources and sites through empirical legal research guides published by dozens of law schools, including the University of Arizona College of Law and the University of Chicago Law School.

4.1 Data sites offer more than data: The case of the IPUMS USA documentation center

Many data sites offer more than just data. For instance, U.S. Census Bureau sites will often link to descriptions of the underlying research methodology (e.g., for the American Community Survey (ACS)), reports and publications that use the data, and more. the IPUMS site maintained by the University of Minnesota, “provides census and survey data from around the world integrated across time and space” (University of Minnesota, 2021). And, the site offers so much more. As noted in Chapter 1, the Documentation Center within the IPUMS USA portion of the website contains U.S. census questionnaires from 1850 to today, including race and disability questions throughout the years. The Documentation Center also details the methodologies behind various census and survey collections and known data issues. These resources are excellent teaching tools because they help students explore and problematize how governments collect data about their citizens.

Second, law librarians can employ data-finding questions to discover more resources for their learning and to help patrons seeking data, statistics, and SSA. The three key questions to ask when seeking new data are:

“1. Who would have an incentive to collect (raw) data about [the] subject?

2. Who would maintain ready-made statistics about [the] subject?

3. Where would we find secondary statistical analysis of this subject?” (Ryan, 2013, p. 32).

Data-collection incentives include government mandates, nonprofit missions, and profit motivations. For instance, federal statutes and regulations require many agencies to report spending data. Organizations such as the World Bank and Vera Institute, which focuses on reducing mass incarceration, collect and publish data and statistics in support of their work. Legal intelligence companies sell profitability data to law firms (e.g., ALM profitability per attorney reports, Thomson Reuters law firm profitability solutions). Once a law librarian identifies the type of entities that must, should, or would want to collect data, that information can drive better Internet searching for those entities and their free or proprietary data holdings.

4.2 Geography as a factor in budget data finding

Geography can be an important factor in who collects data. For instance, U.S. government budgeting and spending data is collected by a host of institutions at the federal, state, and local level, and reported by government agencies and nonprofit organizations. Reporting sites include:

Federal: GPO (https://www.govinfo.gov/app/collection/budget); OMB (https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/); USA Spending (https://www.usaspending.gov/)

States: NCSL (https://www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/fiscal-policy-databases.aspx); Pew Research Center (https://www.pewresearch.org/topic/politics-policy/government/state_local_government/); U.S. Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/state.html); and individual state governments (https://www.mass.gov/operating-budgets-fy23-and-previous) and state-focused nonprofits (https://www.masstaxpayers.org/)

Local: National League of Cities (https://www.nlc.org/resources-training/resource-library/?orderby=date&resource_type%5B%5D=fact-sheet); U.S. Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/gov-finances.html); U.S. Conference of Mayors (https://www.usmayors.org/product/mayors-data-extract/); and local cities and organizations

While governments and organizations around the globe disseminate free data, the best data for some projects, including law firm profit maximization projects and large-sample empirical research projects, often needs to be purchased. Technical service librarians are well-versed in negotiating contracts and can assist reference librarians in knowing how to properly obtain a data, database, or statistical product license. Licensing is a legal process that requires the input of organizational fiduciaries and legal signatories. Even a text and data mining (TDM) license costing a few hundred dollars could require the review of commercial agreements officers, general counsel, fund managers, etc. Once a librarian finds a dataset or database (e.g., Wharton Research Data Services) to buy, the next questions should be: 1) Who will pay for the dataset/database?, 2) Who can authorize the licensing agreement?, and 3) Who will release the funds to purchase the dataset/database? The law librarian should allow several months for complicated licenses, particularly if the dataset/database will be purchased or used by multiple patrons or departments.

Regardless of whether data is found or purchased, law librarians should help patrons think critically about its limitations. For instance and as discussed further below, data about a group of people—such as Newark residents—should accurately reflect the characteristics of those people. When examining survey data on Newark residents, the patron must determine whether the total number of people surveyed is sufficient to permit statistical inference to all Newark residents, and if the numbers in subgroups—Asian residents, men, senior citizens—roughly match their proportion within the actual population. For this second concern, the patron can compare the survey data to demographic data from the U.S. Census or elsewhere.

4.3 Hypothetical survey data usage: African Americans favor lower taxes

Claim in newspaper article: African Americans favor lower taxes

Newspaper article statistic: 66% of African Americans reported that they “strongly favor lower taxes.”

Data behind the statistic: Survey of 1,500 taxpayers in Pittsburgh, who were called at 5pm. 3 participants were African American. 2 of those 3 “strongly favor lower taxes.” (2 out of 3 = 66%)

The point is: law librarians can help patrons critically evaluate found and purchased data to determine its strengths and weaknesses. Librarians and their patrons can also critically appraise bibliometrics.

Gathering Bibliometrics & Understanding the Factors that Drive Citation Counts

Most academic law libraries provide bibliometrics, or research citation statistics, support as part of their scholarly communication services. Bibliometrics support is especially important to junior faculty, as they can use citation statistics to demonstrate their output and impact during the tenure review process. Faculty can also use bibliometrics to select journals for their work, to make a case for their research impact in grant applications, and more. Student editors can use bibliometrics to assess the impact of their law reviews. Attorneys can use citation counts to argue the importance of a given secondary source in a legal brief.

Bibliometric support can be circular: a law librarian will access and discuss a legal researcher’s citation statistics with the researcher, then help that patron diversify or improve their scholarly messaging, then assess if citation counts are rising, and so forth.

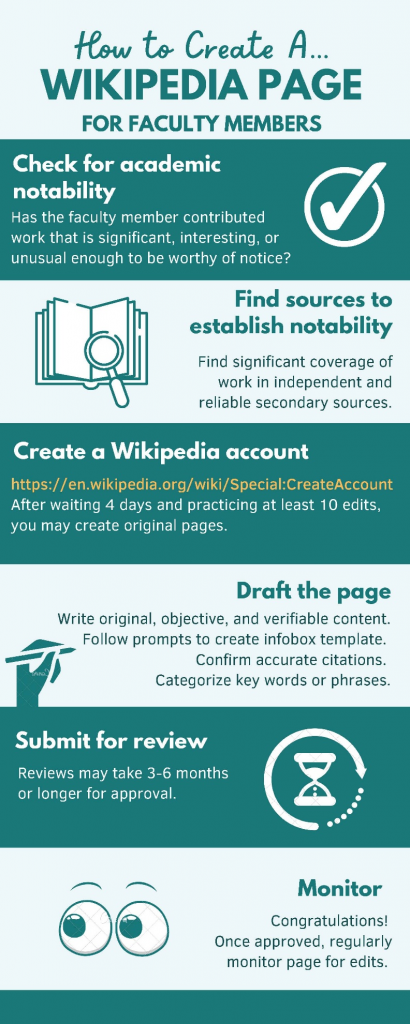

For the scholarly messaging piece, librarians can assist scholars in establishing an ORCID iD (i.e., a scholar’s unique digital identifier); contribute research to repositories; build ResearchGate and SSRN pages; establish a wikidata author item and Wikipedia page; etc. Law librarians can also assist patrons in understanding the algorithms, data, and trends driving the bibliometrics produced by different scholarly venues.

4.4 How to create a faculty Wikipedia page (by Adrienne Kelish)

“How many times has an article been cited?” is a seemingly straight-forward question, but the answer will vary by database (Whisner, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c, 2018d). Legal scholars track their citations in a range of databases, including: HeinOnline, Lexis (Shepard’s), Westlaw (Key Cite), Web of Science, and Google Scholar (Watson, forthcoming; Whisner, 2018a). The citation counts produced by each database—for the same article—vary by what the databases index and how they retrieve citations. HeinOnline covers most U.S. law reviews but uses a Bluebook citation algorithm (e.g., number of articles citing to “52 Loy. U. Chi. L.J. 67”) to retrieve citations (Whisner 2018a). By contrast, Web of Science/Web of Knowledge employs a more flexible algorithm (e.g., including author name) but does not index many law reviews (Whisner, 2018a). Lexis and Westlaw, via their Shepard’s and Key Cite features (respectively), retrieve citations in Supreme Court briefs and other legal materials, but can miss social science citations. Google Scholar captures more interdisciplinary citations but misses Supreme Court briefs and other legal materials. SSRN tracks social media mentions and counts downloads (Watson, forthcoming); this complicates the meaning of “citation” because these references to the work are informal and not managed by editors. As a result, obtaining citation statistics for a given article requires searching across multiple platforms, assembling a master bibliography of citations, and reporting citations as types (e.g., research article, tweets).

“What factors drive citation?” is a different and difficult question, and the subject of countless studies (see, e.g., Ayres & Vars, 2000; Bornmann, & Daniel, 2008; Eisenberg & Wells, 1998; Shapiro, 2021; Shapiro & Pearse, 2011; Whisner, 2018b, 2018c, 2018d, Yoon, 2013). According to social scientists Lutz Bornmann and Hans-Dieter Daniel, seven factors influence the probability of being cited (2008): publication date, research field, journal, article, author, digital availability of the article, and technical issues.

First, publication date affects citation in at least three ways: authors tend to cite more recent studies (see also Ayres & Vars, 2000; Whisner, 2018c); authors cite highly-cited studies, or studies that have circulated long enough to be highly-cited; and authors have fewer choices when citing pre-1980s research because there were fewer journals and databases then (Bornmann, & Daniel; Lowe & Wallace, 2011), and some pre-Internet content has yet to be digitized.

Second, each field has its own citation practices and trends (Bornmann, & Daniel). Historians might be more open to citing older research. Small specialty fields have fewer researchers citing each other. Legal scholars tend to cite articles from law reviews at higher ranked law schools (i.e., per U.S. News & World Report rankings; Ayres & Vars, 2000; Whisner, 2018b), though articles at lower ranked schools can break through when they address unique areas of law (Whisner, 2018c). Law librarianship is a low-citation field; a typical law librarianship article will receive three or fewer citations (Togam & Mestri, 2021). Field differences matter when faculty and librarians are judged by interdisciplinary tenure, promotion, and awards committees.

Third, journals generate different average per-article citations (Bornmann, & Daniel), a phenomenon that drives journal impact factor. In legal research, articles appearing in the flagship journals of highly-ranked law schools enjoy more citations than most other law reviews (Ayres & Vars, 2000; Eisenberg & Wells, 1998; Whisner, 2018b). This holds true even for student-authored notes and comments in the Harvard Law Review (Whisner, 2018b). In Communication, Communication Monographs has a much higher impact factor than any other U.S. journal in the field (National Communication Association, 2022). A host of factors drive journal impact metrics, including editorial bias (Yoon, 2013), marketing, number of issues per year, and more (Bornmann, & Daniel).

Fourth, article factors drive citations (Bornmann, & Daniel). The first article in an issue tends to receive higher citations (Bornmann, & Daniel). Letters, book reviews, and other short pieces tend to receive fewer citations (Bornmann, & Daniel). Article length also drives citations (Bornmann, & Daniel) though legal scholars see diminishing returns for length once a law review article has met a typical threshold (i.e., 40-70 pages; Ayres & Vars, 2000).

Fifth, authorship characteristics affect citation frequency. In many social sciences, co-authored articles are more heavily cited than solo-authored articles (Bornmann, & Daniel). In the law, that correlation is weaker (Ayres & Vars, 2000), in part because law reviews publish far more solo-authored articles than social science journals (Tietz, Price, & Nicholson, 2020). Historically, men received substantially more citations to their work than women (Bornmann, & Daniel), and White scholars received more citations than scholars of color (Bell, 2007; Nunna, Price II, & Tietz, forthcoming), though Ian Ayres and Frederick Vars found that women and non-White authors fared better when they published in the Harvard, Stanford, or Yale law journals. Law professors are cited more often than law students (Whisner, 2018d). Social networks and scholarly connections drive citations too, as authors favor people they know personally (Bornmann, & Daniel), and law professors acknowledge and cite authors from their own law schools more frequently than scholars at other schools (Ayres & Vars, 2000; Tietz, Price, & Nicholson, 2020).

Sixth, availability of articles in digital and open-access formats positively correlates with citations (Bornmann, & Daniel). Seventh, technical issues affect citation, including misspelled author names and publication information in metadata and reference lists (Bornmann, & Daniel; Watson, forthcoming).

Law librarians should understand how to retrieve citation counts and how to explain the factors driving those counts. Law librarians should also care about bibliometrics because they affect our scholarly communication and professional advancement. Similarly, law librarians should be conversant in law library metrics and assessment because these statistics affect our individual and collective professional strength. Librarians can approach library assessment as an opportunity to learn about research design, data collection, dataset construction, statistical analysis, and reporting.

Collecting Library Data, Creating Datasets, Analyzing Trends, and Reporting Information

Law librarians collect data and report statistics to numerous stakeholders. For instance, U.S. academic law libraries submit library statistics to the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), Association of Research Libraries (ARL), U.S. News & World Report (USNWR), their law school deans, and others (McAllister & Brown, 2019; NELLCO, 2021; Panella, Iaconeta, & Miguel-Stearns, 2017). Prior to 2017, the American Bar Association (ABA) also collected extensive information from academic law libraries (Panella, Iaconeta, & Miguel-Stearns). In 2014, Teresa Miguel-Stearns, then director of the Lillian Goldman Law Library at Yale Law School, led the charge to consolidate data reporting into a single system that would enable library directors to pull reports for different stakeholders and benchmark their collections and services against peer libraries’ collections and services (Panella, Iaconeta, & Miguel-Stearns). Today, the national reporting and benchmarking system, known as ALLStAR, is maintained by the NELLCO consortium (NELLCO, 2021).

For reporting and benchmarking, library directors collect data from every department. Technical services librarians provide usage counts for databases and eResources (McAllister & Brown). Reference librarians aggregate data from patron interactions and reference questions. Access Services librarians gather circulation data. All departments report spending and personnel data. Commonly reported data are organized into 10 categories in the ALLStar 2021 survey (Figure 4.5). Because information services are boundary-crossing, ALLStAR items sometimes appear in non-obvious categories. For instance, library directors reported some circulation statistics in the Services section of the 2021 ALLStAR survey (NELLCO, 2021).

4.5 ALLStAR survey sections and categories

Section 100. Personnel – FTE, Headcount and Hours

Section 200. Expenditures, Personnel (e.g., total student assistant wages)

Section 300. Expenditures, Non-Personnel (e.g., one-time book purchase, staff development expenditures)

Section 400. Collections

Section 500. Services (e.g., circulation/usage statistics)

Section 600. Interlibrary Loan

Section 700. Facilities

Section 800. Degrees, Faculty & Enrollments (e.g., number of full-time instructional faculty)

Section 900. Information Technology

Current Issues Questions (e.g., “What implications did the COVID-19 pandemic have for library personnel and staffing during FY21?”)

While library benchmarking can involve the whole staff in data collection and dataset creation, it can also allow empirical librarians to practice their trend analysis and reporting skills. For instance, librarians have been challenged to estimate post-pandemic eResource usage (Lowe, 2020). This estimation was difficult in the early phase of the pandemic because there was insufficient data for a pre- and post-emergency comparison. Now that we have years of pandemic-era data and visitor restrictions have relaxed, we can better predict future eResource usage. Empirical law librarians can produce data charts and research write-ups to help administrators effectively budget for eResources.

Assisting with Original Data Collection/Creation

While many legal research questions can be answered with existing demographic, legal system, or other data, some require the collection of new—or “original”—data. Empirical legal researchers can collect data via a host of methods and instruments, including interviews and surveys. Original data collection/creation requires a systematic process and ample planning. Data collection begins with the articulation of hypotheses and research questions.

4.6 Notes from the Desk of Sarah E. Ryan: My empirical research on empirical law journals

In 2021, I started a multi-year study of law and social science journal content. As part of the project, I asked: what methods are used in empirical legal research journals? I chose the Washington & Lee (W&L) law journal rankings as the sampling frame, or master list of relevant journals. Using the W&L website, I selected the Social Sciences and Law subject category, and the 10 journals with the highest combined impact factors for 2020. A doctoral research assistant and I gathered all of the 2020 articles from those 10 journals and I analyzed roughly three dozen articles from three journals with different aims and scopes (i.e., Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Law and Human Behavior, and Law & Social Inquiry). From that analysis, I developed a list of the research methods I saw. I defined the methods as I had seen them used in empirical law journals and created a content analysis instrument, or worksheet, for our research team members to complete for each journal article (see Ryan, Behpour, Bonds, & Xiao, under review). The methods listed and defined in the content analysis instrument are not an exhaustive list, nor would all researchers describe their methodologies in exactly these terms. They include non-data, existing data, and original data collection methods. Common original data collection methods appear in bold type.

–content analysis (analyzes a set of cases, laws, etc. using a repeated method applied to each item by an actual human being; the method or instrument used is usually described, unlike legal analysis; a human reads the documents unlike machine analysis)

-dataset analysis-ad hoc (quantitatively analyzes an existing dataset such as a dataset collected by the Census Bureau)

–experiment (designs a test, role-play, or hypothetical scenario and asks participants to engage as if it were real in order to study their actions, choice-making, etc.)

–focus group (analyzes discussion among three or more participants, assembled together in person or online, of prompts or questions, or talk about their preferences toward a product or intervention)

–interviewing (conducts interviews with individuals to gain research information/data; this technique allows for some conversation unlike surveys)

-legal analysis (interprets select cases, laws, etc. but does not collect a sample, code the cases, etc.; the author does not describe an instrument or method applied to each item unlike content analysis)

–machine analysis (analyzes a set of cases, laws, etc. using machine processing; unlike content analysis, humans do not do most of the coding coding)

-meta analysis (analyzes published scholarship to determine trends; while every article will review literature a meta-analysis uses the literature as its dataset and the researchers report lit- trends in their findings or discussion)

–nonparticipant observation (observes people from a distance and/or studying their behavior without joining in on what they are doing)

–natural experiment (analyzes data from a social division that occurs naturally or outside the research; for instance Kansas City crosses two state lines and can serve as a natural experiment site for state law research)

–participant observation (observes people while participating in activities or events with them)

–randomized controlled trial (conducts an experiment in which some people, interventions, etc. are assigned as tests and others as controls)

–survey (poses a set of questions to interview subjects in-person or through an online survey mechanism such as MTurk; this technique does not allow for conversation like interviews)

The first and second steps of data collection happen in conversation. The first step is to articulate research questions and/or hypotheses (Ryan, 2015). The Hs and RQs inform every choice, just as a library’s mission statement would guide collection development, services, staffing, etc. The second step is to conduct a thorough literature review, which can prompt re-writing of the Hs and RQs and yield data collection instruments.

The literature review helps the researcher identify guiding theories, prominent debates, identical or pre-empted research, and unresolved methodological or applied research issues (Ryan, 2015). The literature review can also surface research instruments, such as semi-structured interviewing scripts. When a patron seeks to expand a current area of research to a new population, location, etc., she should use an existing and validated data collection instrument (see Chapter 5) if possible.

The third step in data collection is optional but helpful: to articulate the proposed significance and impact of the research (Ryan, 2015). While definitions of these terms vary, significance often refers to the scholarly contribution the researcher hopes to make, or how he will expand or improve the research field with this research (Ryan, 2015). Significance responds to the question: What is lacking in this field now? Impact usually refers to the lasting contribution that the research will make to the real world and/or field (Ryan, 2015). Impact responds to the question: How powerful will this research be? (see NIH, 2016). Significance and impact statements are often required in research grant proposals. Outside of those documents, significance and impact statements can still help researchers articulate and adhere to a mission or vision for the data collection.

The fourth step in data collection is the study design. When designing the study, researchers should answer six questions (Ryan, 2015):

- What is my unit of analysis? (e.g., individual people, organizations, nations)

- Who/what am I studying, or what is my population?

- How will I sample that population?

- How will I collect data from that sample?

- How will I manage my data before, during, and after data collection?

- How will I clean, process, and analyze my data (e.g., statistics software)?

Each of these questions assumes knowledge of research methods terms and practices. For instance, a sample is a selection of people, organizations, documents, etc. from a defined population. If the study population is Texas residents, of which there are nearly 30 million, a sample might include 1,500 Texas residents. For researchers to make choices about representation in the sample—geographic, racial, gender identity, etc.—they must first understand how a sample relates to a population (Ryan, 2015). When collecting data from humans, researchers should also be familiar with the work of institutional review boards (I.R.B.s).

Human Research Subjects Considerations and I.R.B. Services

Researchers should treat their human research subjects ethically, fairly, and with respect (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1979). Unfortunately, many researchers have violated these fundamental requirements for human research. For instance the U.S. Public Health Service studied the effects of untreated syphilis in Black men in the south from 1932-1972 (CDC, 2021). The government agency recruited men without informing them of the risks of untreated syphilis, collected their health data while they were sick, and did not offer them treatment, even as they were dying (CDC, 2021). The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and a host of studies like it, prompted the U.S. government to regulate human subjects research (CDC; U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare). Today, the federal government requires institutions seeking federal research funds to maintain I.R.B.s. Most universities and hospitals—and their research partners on federal grants (e.g., corporate partners)—are required to maintain human subjects boards. By contrast, legal analysis and competitive intelligence firms might not maintain I.R.B.s if they are not engaged in federally-funded research. Nevertheless, law librarians can help all researchers to consider the ethical implications of their human data collection.

Because librarians are researchers, we can serve on I.R.B.s. This can be an invaluable immersion in research ethics and human subjects regulations. Absent that immersion, law librarians can still advise their patrons that there are rules for how they recruit research participants, engage them during data collection, pay them for participation, handle their data, etc. (see CITI Program; Klitzman). Law librarians can then direct these patrons to the organization’s I.R.B. or research ethics office. If the firm or organization does not have such an office, librarians can direct patrons to low cost trainings, such as the CITI Program’s widely respected program for socio-behavioral-educational research (CITI Program).

4.7 Hypothetical data collection procedures: Analytics firm focus group strategies

Legal analytics firms such as ALM Global, LLC collect research to help law firms better compete against each other. Some of this research involves human subject interviews or surveys. Imagine a study of second-year associates—on the partner track but not yet law firm partners—and their supervisors. The analytics firm researchers plan to conduct focus groups with junior associates and the partners at their firms. The goal of the research is to encourage dialogue across the tiers of recruited firms/participants and to offer insights to sampled partners during the research process. As part of the research participant recruitment efforts, the analytics firm asks partners to invite the second-year associates working on their teams to participate. What ethical issues might this participant recruitment and data collection research design introduce?

Data Project Management Considerations

Data-driven projects vary greatly. Some require ample time for planning and execution, while others can be completed quickly. Some require the support of a large research team, while others can be handled by one or two researchers. Law librarians can assist researchers in understanding the factors that drive resource needs for empirical projects (Ryan, Rashid, & Ali, under review). For existing/found data projects, cost-drivers include: 1) the cost of the data; 2) its current format; 3) data storage costs; 4) the type and complexity of the desired research analysis (e.g., geospatial modeling); 5) the availability of disciplinary or technical specialists (e.g., a network-analysis specialist); 6) the availability of research assistants to clean data, etc.; and 7) the flexibility and commitment of the lead researcher, or principal investigators (see Ryan, Rashid, & Ali).

For original or mixed data projects (i.e., combination original data and found data), the researchers should factor in the unique costs associated with their data collection and analysis methods. For example, researchers conducting a national survey in a foreign country often hire a survey distribution firm. Interviewers often use recording devices and might need to hire transcriptionists. Archival researchers can require digitization services and the creation of new metadata. These patrons can underestimate the resources required to produce new, original data from old documents (see Eiseman, Bagnall, Kellett, & Lam, 2016). Law librarians can walk patrons through the lifecycle of data projects—from research question formulation through post-publication data storage—to help them properly estimate the resources they will need to bring the projects to a successful conclusion.

Reflection Questions

- Prior to reading this chapter, what did you believe drove citation counts? Has your understanding of citation count influences changed? If so, how? If not, which facts or ideas in this chapter reinforced your existing beliefs?

- Would you feel competent to help your institution gather internal performance data? If yes, where did you acquire these skills? If no or not yet, how could you gain additional data collection skills?

- What websites and repositories have you used to find data? Do you have favorites? Are there sites you have been hoping to visit?

- In your opinion, how can librarians best assist patrons with original data collection?

References

Ayres, I., & Vars, F. E. (2000). Determinants of citations to articles in elite law reviews. Journal of Legal Studies, 29(1), 427-50.

Bell, M. (2007). The obligation thesis: Understanding the persistent ‘Black voice’ in modern legal scholarship. University of Pittsburgh Law Review, 68(3), 643-99.

Bornmann, L., & Daniel, H. D. (2008). What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behavior. Journal of Documentation, 64(1), 45-80.

Eiseman, J., Bagnall, W., Kellett, C., & Lam, C. (2016). Litchfield unbound: unlocking legal history with metadata, digitization, and digital tools. Law and History Review, 34(4), 831-855.

Eisenberg, T., & Wells, M. T. (1998). Ranking and explaining the scholarly impact of law schools. The Journal of Legal Studies, 27(2), 373-413.

Klitzman, R. (2013). How IRBs view and make decisions about coercion and undue influence. Journal of Medical Ethics, 39(4), 224-229.

Lowe, M. S., & Wallace, K. L. (2011). Heinonline and law review citation patterns. Law Library Journal, 103(1), 55-70.

Lowe, R. A. (2020). How to evaluate and license an e-resource during a pandemic (without scheduling a meeting). Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 32(4), 307-315.

McAllister, C., & Brown, M. (2019). Wrangling weirdness: Lessons learned from academic law library collections. Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference. doi:10.5703/1288284317168

National Communication Association. (2022). C-brief. https://www.natcom.org/sites/default/files/publications/NCA_CBrief_Vol12_1.pdf

NELLCO. (2021). FY21 ALLStAR official survey [Excel spreadsheet]. https://www.nellco.org/page/AOS

NIH (National Institutes of Health). (2016, March 21). Overall impact versus significance. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/peer/guidelines_general/impact_significance.pdf

Nunna, K., Price II, W. N., & Tietz, J. (forthcoming). Hierarchy, race & gender in legal scholarly networks. Stanford Law Review, 75.

Panella, J. C., Iaconeta, C., & Miguel-Stearns, T. M. (2017, November/December). ALLSTAR benchmarking: How collaborating on collecting and sharing data is a win-win. AALL Spectrum, 22(2), 12-17.

Ryan, S.E. (2013). Data, statistics, or secondary statistical analysis: Helping students articulate and acquire the numbers they’re (really) seeking. Perspectives: Teaching Legal Research and Writing, 22(1), 30-34.

Ryan, S. E. (2015). Teaching empirical legal research study design: Topics & resources. Perspectives: Teaching Legal Research and Writing, 23(2), 152-157.

Ryan, S. E. (2016). Human subjects research review: Scholarly needs and service opportunities. Law Library Journal, 108(4), 579-598.

Ryan, S., Behpour, S., Bonds, C., & Xiao, T. (under review). Dissonant reflections on a quarter-century of JIEL: Authorship, methods, geographies, and subjects.

Ryan, S. E., Rashid, M. & Ali, I. (under review). Data-driven empirical research costing: Using scholarly literature, open government data, and formative case studies to plan projects.

Shapiro, F. R. (2021). The most-cited legal scholars revisited. University of Chicago Law Review, 88(7), 1595-1618.

Shapiro, F. R., & Pearse, M. (2011). The most-cited law review articles of all time. Michigan Law Review, 110(8), 1483-1580.

Tietz, J. I., Price, W., & Nicholson, I. I. (2020). Acknowledgments as a window into legal academia. Washington University Law Review, 98(1), 307-351.

Togam, M. B., & Mestri, D. (2021). A bibliometric study on ‘Law Librarianship.’ Library Philosophy and Practice, 6801.

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. (1979). The Belmont report. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/the-belmont-report-508c_FINAL.pdf

Watson, A. (2022, forthcoming). The unintentional consequences of unintended datasets. Law Library Journal.

Whisner, M. (2018a). Practicing reference: My year of citation studies, Part 1. Law Library Journal, 110(1), 167-80.

Whisner, M. (2018b). Practicing reference: My year of citation studies, Part 2. Law Library Journal, 110(1), 283-94.

Whisner, M. (2018c). Practicing Reference: My Year of Citation Studies, Part 3. Law Library Journal, 110(1), 419-28.

Whisner, M. (2018d). Practicing Reference: My Year of Citation Studies, Part 4. Law Library Journal, 110(1), 561-77.

Yoon, A. H. (2013). Editorial bias in legal academia. Journal of Legal Analysis, 5(2), 309-338.