2 Empirical Legal Reference Work: Background Knowledge & Interviewing

Empirical legal reference conversations often begin like other reference interviews, with questions about the patron (e.g., law student?), the topic, the purpose (e.g., trial exhibit?), point in the project, and deadlines (Hickman, Kearney, & Leong, 2020). But early on, the librarian will learn that the patron wants to find social science research, data, or statistics, or that the patron wants to conduct empirical legal research. At that point, the interview requires an empirical reference approach.

Empirical legal research has specialized assumptions, vocabulary, resources, and tools. Developing an empirical reference approach is important for three reasons. First, empirical literacies are needed for search strings, data services and license negotiations, and more. Second, librarians need to prepare for future empirical work (see Hickman, Kearney, & Leong, 2020). Third, librarians can leverage empirical literacies to calibrate their recommendations (Tucker & Lampson, 2018).

Chapter learning objectives

- Describe the four literacies of empirical legal reference work

- Recognize empirical legal research terms, assumptions, and methods

- Evaluate the quality of hypotheses and research questions

- Develop professional development strategies for gaining empirical knowledge

Abbreviations and specialized terms

algorithmic literacy, artificial intelligence (AI), bibliometric statistics, Conference on Empirical Legal Studies (CELS), data literacy, dependent variable, descriptive statistics, hypothesis, independent variable, inferential statistics, International Conference on AI and Law (ICAIL), machine learning (ML), mixed methods, natural language processing (NLP), qualitative methods, quantitative methods, research question, secondary statistical analysis, social scientific literacy, statistical literacy, variable

Developing Empirical Literacies

Data, statistics, and algorithms surround us. Whether we consider ourselves “numbers people” or not, legal information work requires us to use data and to help others find it (Whisner, 2003; 2016). As law has become an interdisciplinary academic field (Whisner, 2003) and a data-driven profession (Robert, 2019), law librarians have broadened their knowledge of statistics, artificial intelligence, and more (Robert, 2019; Whisner, 2016). For law librarians from non-empirical backgrounds, developing empirical expertise requires self-confidence, the humility to develop new literacies (Garingan & Pickard, 2021; Whisner, 2016), and the wisdom to admit when it is time to reach out to subject matter experts (e.g., data librarians).

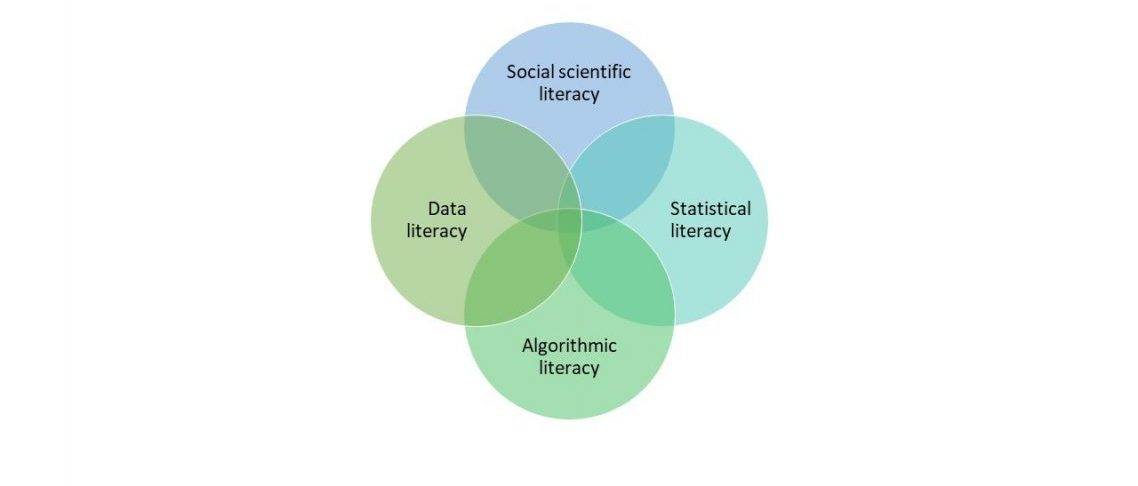

Empirical legal reference work draws upon four literacies: social scientific, data, statistical, and algorithmic (2.1)

2.1 Four literacies of empirical reference work

Social Scientific Literacy

Social scientific literacy reflects two understandings and related capacities. First, the law librarian must recognize that the social sciences are a diverse set of overlapping disciplines with contested histories and evolving assumptions and practices. Law librarians can become conversant in the histories of the social sciences by reading early twentieth century journal articles and professional society publications, reviewing historical curricula and lecture notes, and studying watershed debates in the field. For instance, Anthropology had a reckoning during the African independence era that followed World War II, when “[western] anthropologists began to realize how profoundly their discipline had been involved in colonialism, subjugation, and war” (Ryan, Hebdon, & Dafoe, 2014, p. 187; see also Kasakoff, 1999). Viewed in a new light, much of the field’s foundational work (see Figure 2.2) was invalid, unreliable, and biased.

With regard to the superstitions and beliefs of the Papuans, owing to our unfortunate difficulties with the language we learnt nothing whatever. Religion, in the accepted sense of that term, I am sure they have not. It is true that they make curious carved effigies, but these are not idols, and there is no evidence to show that they ever consult or worship them; on the contrary, they treat them with contempt and often point to them with laughter. These images are ingeniously and skillfully [sic] carved out of wood, and they represent a human figure always grotesque and sometimes grossly indecent. They vary in size from a few inches to twelve or fourteen feet, and when they are not neglected they are ornamented with red and white paint.

Following the debates of the 1950s, many anthropologists refused to conduct “natives” studies and instead embraced participatory methods with engaged local groups (Kasakoff). For some social scientists, Anthropology’s move toward integrative, holistic, and inclusive practices (Ryan, Hebdon, & Dafoe) rendered the field less social scientific (Kasakoff). The point for law librarians is that historical debates and resources can foster specialty knowledge and social scientific literacy.

Second, law librarians must become acquainted with social science research methods and tools. These methods can be quantitative (e.g., Imbens & Rubin, 2015), qualitative (Creswell & Path, 2017; Patton, 2014), or both (i.e., “mixed methods.” See Banyard, Winder, Norman & Dillon). For instance, historical researchers often perform intertextual analysis to discover narratives or arguments spanning primary source documents (Whisner, 2003). Historical research requires document identification, retrieval, and critical reading skills (Whisner, 2003). If a historical project is described as political history or historical political economy, the research will incorporate methods from political science and/or economics. Political economy research will often include statistical analysis because statistics are key evidence for economists. If an anthropologist joins a research team, the project could involve participatory sketching, field work, or other en situ methods. If a legal expert joins the team, the research might feature cases that demonstrate the historical, political, or group trends described by the other researchers, such as City of Seattle v. Buchanan (1978) (Figure 2.3), a case that turned on legal-anthropological arguments (Figure 2.2, infra).

In City of Seattle v. Buchanan (1978), the all-male Supreme Court of Washington upheld an ordinance that prohibited lewd conduct and the public exposure of one’s genitals or female breasts. Five women were arrested at the Seattle Arboretum for swimming and sunbathing with exposed breasts. They were convicted and fined $100 each. The women argued that the ordinance violated the equal rights amendment because male breasts were not included in the ordinance. The women provided the expert testimony of a physician who said there is no difference between male and female breast composition, nor are breasts considered a primary sex characteristic. However, the Court found that, other than lactation, the primary function of women’s breasts was for male sexual arousal (Whisner, 1982). The Court referenced an Atlanta, Georgia ordinance that required storefronts to have the shades drawn when undressing female mannequins over concern that male passersby were becoming distracted by the female form. Several of the justices took issue with lewdness argument because it stigmatized the women. The dissent found the ordinance unconstitutional but remained silent as to whether the state had the right to regulate when and where women must cover their bodies.

Beyond preferred methods, the social sciences can also be conceptualized as hypothesis-dominant and question-dominant fields. Hypothesis-driven researchers in Economics, Political Science, and Sociology test the relationships among variables such as income and educational attainment; or neighborhood, social affiliations, and likelihood of gunshot injury (Tracy, Braga, & Papachristos, 2016). Question-driven researchers in Anthropology, Communication, and History craft inquiries about social groups, phenomenon, or events. Of course, researchers across the disciplines employ both hypotheses and research questions. In fact, the best research often involves a recursive, or circular, process of asking broad research questions to gain information, using that information to generate hypotheses, discovering unexpected information, and posing new research questions (Chun Tie, Birks, & Francis, 2019).

Data & Statistical Literacy

Data literacy begins with an understanding of what data is and is not. This understanding can evolve into a familiarity with data types, issues, and resources. First, data is not statistics or secondary statistical analysis (Ryan, 2013b). Data is a set of numbers that have yet to be analyzed; data is unprocessed, “raw,” or pre-mathemetized (Ryan, 2013b). If you have a spreadsheet of numbers that has yet to be analyzed, you have data.

Statistics are the numerical result of mathematics performed on data. The Cincinnati median single-family home price is a statistic derived from a set of Cincinnati home prices. Many social scientific journal articles include descriptive statistics that summarize the data for a variable, several variables, or an entire data set. Typical descriptive statistics include counts (e.g., n = 213 cities included in the study), means/averages, and standard deviations, or mathematical indicators of how the data spreads out from the average.

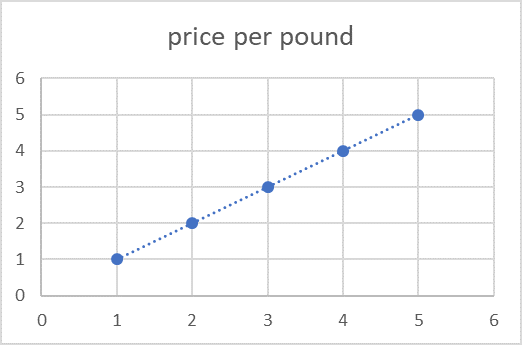

Some articles, especially in Economics, will include inferential statistics based upon mathematical assumptions and models. First, the researchers will select a model that matches their research assumptions. For instance, an ordinary least squares regression model assumes a correlational relationship between two or more variables that can be demonstrated by a line, such as a 1:1 relationship between the weight and cost of dog food (e.g., 1 lb. = $1; Image 2.4).

2.4 Linear regression graphic example

Second, the researchers will perform the appropriate statistical tests on their data, typically using statistical software (e.g., R, SPSS, Stata; e.g., Stata code for an OLS calculation of Cincinnati home price in relation to Title I school proximity: regress homeprice T1schoollocation).

Stepping back from social science journal articles, the point is that some of what we call data is actually statistics because a researcher has applied mathematics. Even counts, such as 432 homes are included in the dataset, are statistics. Bibliometric statistics, such as citation counts and proportions, are an example of statistics that are frequently described as data.

Why does the data versus statistics distinction matter? Because it reminds us that there can be problems in two areas: the data and the mathematized numbers associated with the data. Data can be missing or unreliably collected, or researchers can make a math error or chose the wrong model based upon faulty assumptions such as no volume discounts (i.e., every pound of dog food increases the total cost). These issues are important to consider, even when patrons are requesting secondary statistical analyses (SSAs).

“Secondary statistical analyses are writings that interpret statistics” (Ryan, 2013b, p. 30). Many federal government agencies produce SSAs, as do think tanks and academic research centers. When legal researchers need a piece of empirical evidence to support a broader point they will often employ SSAs. For instance, if the broad point is that Congress passed the First Step Act of 2018 to ameliorate federal prison overcrowding, the researcher might cite SSA on inmate population totals from the Federal Bureau of Prisons (see, e.g., Ryan, 2020). Again, the distinctions among terms such as data, statistics, and secondary statistical analysis matter for analytic reasons. An appreciation of these differences also helps us find the right information for our patrons. So too does algorithmic literacy.

Algorithmic Literacy

Algorithmic literacy reflects one core understanding and a host of related capacities. First, the law librarian must recognize that computer algorithms, or sets of coded rules, are at work in “technologies that retrieve, suggest, predict, summarize, and stipulate the law on specific areas based on user inputs[.]” (Garingan & Pickard, 2021, p. 97). Then, the law librarian must be able to explain algorithmic terms and effects to patrons. Key terms include natural language processing (NLP), machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI).

Natural language processing can serve patrons throughout the research process, even if they are unaware of its operation. All databases have code that helps them make sense of human-typed search terms and apply the human input to (meta)data in underlying content. This human-to-computer language translation is facilitated by NLP code. Natural language processing techniques also enable legal researchers and information companies to efficiently analyze the content of large corpuses such as a year of state session laws or hundreds of consumer contracts. For instance, an NLP algorithm known as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) discerns linguistic relationships in a corpus and generates data about the language (Ryan, Rashid, & Ali). That data can then be used for prediction.

Machine learning is a related and sometimes overlapping term with NLP. But, ML focuses on model-creation. Machine learning models require programming (e.g., Python), research design skills, and tools such as dictionaries. An ML model can use linguistic data to predict language in new documents, such as phrases that two documents would share if they were closely related (Sanyal, Bhowmick, Das, Chattopadhyay, & Santosh, 2019). In our recent work, an ML model flagged names and pronouns in law files as a means of identifying private laws (i.e., which focus on identifiable individuals unlike public laws; Ryan, Hong, & Rashid). Specifically, we used the spaCy dictionary of named entities to find people, organizational, country, and other names in our files (Ryan, Hong, & Rashid). All of this ML work is possible because of developments in artificial intelligence.

Artificial intelligence is generally considered the umbrella term for NLP and ML. Artificially-intelligent systems deploy complicated sets of procedures in ways that can mimic human thinking and learning. For instance, your digital calendar could discern your repeated Wednesday entries and pop up a window suggesting a recurring event; your paper desktop calendar could never do this. Your digital calendar has AI capacities, but these capacities have been built in by human programmers. The role of humans might seem self-evident, but it will sometimes evade patrons. For instance, they might be frustrated that legal file-sharing systems such as the federal courts’ PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) system cannot generate certain statistical output about their content. Could the PACER system produce robust statistical output about the content of documents litigants upload to it? Almost certainly. But the system was not designed for that purpose and human coders have not programmed PACER in that way. Humans would need to write NLP code and develop an ML model for discerning certain language in court documents, collecting that language into datasets, applying mathematics to yield statistics, and producing output in a form useful to researchers. These steps would make PACER more artificially intelligent about federal court filings.

Preparing for Empirical Reference Work

Law librarians should prepare for empirical reference work by honing their empirical literacies, reading empirical research, learning the basics of study design, and exploring data resources.

Law librarians can prepare for empirical work by increasing their empirical consumption (Whisner, 2016). This can include general readership books written by renowned social scientists (e.g., Kahneman, Sibony & Sunstein, 2021; Sachs); newsletters, email lists, and social media feeds from government data-producers such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Whisner, 2016); law librarians’ empirical research guides, blogs, and conference workshops; and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) in social science topics. Reticent empiricists should not delay this immersion because they do not feel academically prepared. As Mary Whisner, Public Services Librarian at the University of Washington Law School and long-time author of the “Practicing Reference” column, advises: Don’t fear. Authors who write for a general audience do not expect readers to have advanced mathematics training.

2.5 Law Librarian Spotlight: Mary Whisner brief biosketch

From 1999 to 2019 Mary Whisner published roughly 75 “Practicing Reference” columns in the Law Library Journal. Her essays covered a range of topics from how recognizing weaknesses can allow for increased productivity (Whisner, 2012), to investigating legal lexicons (Whisner, 2017), to an opinion piece on the current state of lawyer directories (Whisner, 2014). Ms. Whisner tackles controversial topics in her writing, including racial inclusivity and the need for cultural competency within legal research (Whisner, 2014). Her first publication, as a law student, discussed gender-specific clothing regulations and the sexualization of women under the law (Whisner, 1982; see City of Seattle v. Buchanan, supra). Ms. Whisner clerked for Judge Stephanie K. Seymour of the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit and worked as an attorney in Washington D.C. before beginning her law librarian career. In 1988, she joined the Marian Gould Gallagher Law Library at the University of Washington School of Law. Since then, she has served the Gallagher Library in several roles, including her current role as Public Services Librarian. Ms. Whisner has received numerous honors and awards for her notable contributions to the profession and society, including: the University of Washington Distinguished Librarian Award (2009), the Roy M. Mersky Spirit of Law Librarianship Award (recognizing her work with the Youth Tutoring Program) (2014), and the American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) Marian Gould Gallagher Distinguished Service Award (2021). She was inducted into the AALL Hall of Fame in 2021. Ms. Whisner holds a B.A. from the University of Washington, a J.D. from Harvard Law School (where she was editor-in-chief of the Harvard Women’s Law Journal), and an M.L.I.S. from Louisiana State University.

Second, law librarians can learn study design, including the basics of hypothesis and research question construction. These outputs are important because they dictate the sorts of data, statistics, and/or secondary statistical analysis needed.

A broad thesis or topic is the foundation for a good research question. The research question should add inclusion/exclusion information, or words that indicate what the research will and will not include (Ryan, 2015). For instance, U.S. federal drug sentence lengths is an interesting broad topic. Related research questions could suggest a historical or longitudinal approach to the topic (e.g., after 1980), a specific drug of interest (e.g., cocaine base), a focal location (e.g., in New England courts), etc. Patrons can refine their topics into research questions by considering who, what, when, where, how, and why (Ryan, 2015) and then working with the librarian to construct a question(s) that is clear, focused, and answerable. For example: RQ1: Did cocaine base sentencing lengths in federal courts in the New England states change under the Obama Administration? While a research question involves an educated hunch—e.g., sentencing changed under a certain presidential administration—the question format indicates that the researcher does not have enough information to pose a testable statement, or hypothesis.

Second, law librarians can learn study design, including the basics of hypothesis and research question construction. These outputs are important because they dictate the sorts of data, statistics, and/or secondary statistical analysis needed.

A broad thesis or topic is the foundation for a good research question. The research question should add inclusion/exclusion information, or words that indicate what the research will and will not include (Ryan, 2015). For instance, U.S. federal drug sentence lengths is an interesting broad topic. Related research questions could suggest a historical or longitudinal approach to the topic (e.g., after 1980), a specific drug of interest (e.g., cocaine base), a focal location (e.g., in New England courts), etc. Patrons can refine their topics into research questions by considering who, what, when, where, how, and why (Ryan, 2015) and then working with the librarian to construct a question(s) that is clear, focused, and answerable. For example: RQ1: Did cocaine base sentencing lengths in federal courts in the New England states change under the Obama Administration? While a research question involves an educated hunch—e.g., sentencing changed under a certain presidential administration—the question format indicates that the researcher does not have enough information to pose a testable statement, or hypothesis.

A solid hypothesis includes four elements: 1. An outcome, or dependent, variable; 2. One or more trigger or causal variables, known as independent variables; 3. A verb that marries the dependent and independent variables; and 4. “boundary words that include and exclude some groups, time periods, conditions, etc.” (Ryan, 2015, p. 152). Dependent variables are tied to real-world outcomes such as citizen satisfaction with judicial processes, contract negotiation behaviors, and misidentifications in criminal line-ups (van den Bos, K., & Hulst, 2016). Independent variables are characteristics, actions, or events that might cause or influence (i.e., correlate with) the dependent variable to happen. Most research studies have more independent variables than dependent variables (Figure 2.6) and multiple hypotheses.

Dependent Variable Self-reported civil juror satisfaction with verdict

Independent Variables

| Age of judge | Age of juror | Amount of compensatory award |

| Defendant: individual v. corporation | Gender of judge | Gender of juror |

| Length of trial (days) | Nature of case: fraud, slip-and-fall | Punitive damages amount |

| Race of judge | Race of juror | Season when trial started |

| Season when trial ended | Time spent on jury instructions | Time jury deliberated |

| Socio-economic status of juror | Voir dire screening via tablet (yes/no) | Whether jury allowed to ask ? at trial |

| Boundaries federal courts | Michigan, Ohio | 2020-2022 |

2.6 Hypothetical independent and dependent variables in a study of civil jury satisfaction

A sample hypothesis for this study could be: H1: Male jurors will report higher satisfaction with verdicts than female jurors in civil trials conducted from 2020-22 in federal districts in Michigan and Ohio. Gender is the independent variable in this hypothesis. Satisfaction with the verdict is the dependent variable. The remainder of the sentence adds boundaries to the research.

Since the hypothesis is the premise being tested, most social scientists also state it’s opposite—the null hypothesis—which is only rejected if certain conditions are met, such as statistical support of a certain strength (e.g., at a p value < .05; see Lane et al., 2003).

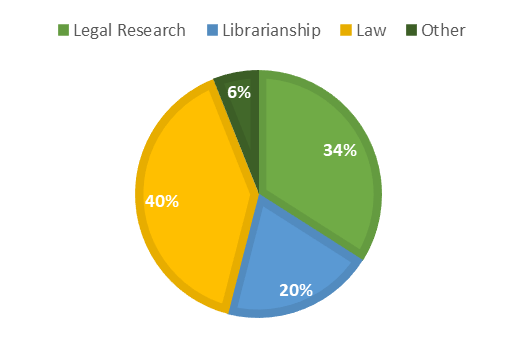

In addition to hypothesis and research question writing skills, librarians should become conversant in common social science research methodologies, particularly survey design and interviewing (see Chapters 5-6). Librarians can develop these skills through social science reading, professional development, and librarian research. Conducting low-stakes research is an excellent way to develop sense memory of terms and their applications. While many librarians lack sufficient time for conducting large-scale social science studies, most conduct research of some sort as part of their work. Librarians can incorporate Hs and RQs into patron satisfaction and quality improvement research, bibliometrics services (Whisner, 2016), and more. For instance, bibliometrics can take different forms than the traditional citations-per-year analysis when the librarian (or patron) poses a novel question, such as: Which of my publication subject areas yields the most citations? (Figure 2.7).

2.7 Citation of Mary Whisner’s publications by article subject

In academic law library settings, bibliometrics and quality improvement research should not require human subjects committee pre-approval, but studies with inmates, litigants, and other citizens might require institutional review board (I.R.B.) pre-approval (Ryan, 2016). When this extra step is introduced, it will add time to the research process but can also yield useful feedback on the study design.

Third, law librarians can lay groundwork for empirical consultations by exploring data resources, as discussed in Chapters 4-5. Librarians can also immerse themselves in data at the Conference on Empirical Legal Studies (CELS), the International Conference on AI and Law (ICAIL), and other empirical legal showcases.

Assessing Patron Knowledge & Calibrating Recommendations

Law library patrons arrive at the reference desk with a range of legal knowledge and experience. The same is true for empirical knowledge and experience. Even if a law firm prefers attorneys with economics training, each person’s empirical skillset will be different. As a result, law librarians need to gauge patron skill through questioning.

Questions about the project can double as skills assessments. For instance, asking about a patron’s hypothesis or research question can reveal if the patron knows how to write those guiding statements. Asking about variables—and assisting the patron in articulating independent and dependent variables—can spark a conversation about prior research work. Asking the patron about data requirements and formats, plans for statistical analysis, and even deadlines can yield insights. For instance, though statistical analysis can be performed relatively quickly, data usually need to be reviewed and cleaned prior to statistical work. If a patron suggests that work on a large dataset can be completed in mere hours after acquiring the dataset, this could suggest a lack of experience with empirical work and should influence the law librarian’s recommendations.

While law librarians help people find what they want, we should also help our patrons to understand how time-intensive and difficult certain resources are to digest and utilize. In the empirical sphere, secondary statistics require less skill to process than raw numerical data. Researchers should take the time to understand how secondary statistical analyses were produced—e.g., sample size, data collection method, statistical assumptions and methods such as trimming—but can incorporate SSA relatively quickly once they are obtained. Numerical data will be more difficult for some patrons to process than narrative data—e.g., interviews, testimonials—and vice versa. A patron with an anthropology or history degree might have a half-dozen approaches to extracting meaning from a corpus of letters whereas an economist might have less sense of how to reliably and validly study letters. When a patron seems less prepared to work with a particular kind of empirical evidence, a law librarian can suggest different or additional resources, subject specialists, potential collaborators, journals that feature similar projects, and more. Tailored recommendations are the end product of a legal reference interview run by an empirically-literate, well-prepared, and thoughtful law librarian.

Reflection Questions

- Do you agree or disagree with the chapter’s premise that the social sciences are divisible into groups? Explain. If you hold a degree in a social science, which assumptions and research methods seem to dominate your field?

- How would you visually depict a recursive research process involving both hypotheses and research questions at different stages of the project?

- Prior to reading this chapter, what was your conception of data versus statistics? Has that changed? If so, how? If not, which facts or ideas in this chapter reinforced your existing beliefs?

- Which data resource would you like to learn more about next? Why?

- What resources exist within your organization and/or professional network to support empirical work?

References

Bancroft Library. (n.d.). Robert Harry Lowie, lecture notes for Anthropology 124, ‘Primitive Religion.’ https://bancroft.berkeley.edu/Exhibits/anthro/6curriculum1_anthropology124.html

Banyard, P., Winder, B., Norman, C., & Dillon, G. (2022). Essential research methods in psychology. Sage.

Burchfield, J. W. (2021). Tomorrow’s law libraries: Academic law librarians forging the way to the future in the new world of legal education. Law Library Journal, 113(1), 5-30.

Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 2050312118822927.

Creswell, J. W. & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Flatley, R., & Jensen, R. B. (2012). Implementation and use of the Reference Analytics module of LibAnswers. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 24(4), 310-15.

Garingan, D., & Pickard, A. J. (2021). Artificial intelligence in legal practice: Exploring theoretical frameworks for algorithmic literacy in the legal information profession. Legal Information Management, 21(2), 97-117.

Hickman, A., Kearney, J., & Leong, K. M. (2020). Reference work. In Z. Joyner & C. Laskowski (Eds.), Introduction to law librarianship. Pressbooks.

Imbens, G., & Rubin, D. B. (2015). Causal inference for statistics, social, and biomedical sciences: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, D., Sibony, O., & Sunstein, C. R. (2021). Noise: A flaw in human judgment. Little, Brown Spark.

Kasakoff, A. B. (1999). Is there a place for anthropology in social science history? Social Science History, 23(4), 535-59.

Kolendo, J. (2019). Reference analytics as an unexpected collection development tool. Collection Management, 44(1), 35-45.

Lane, D. M., Scott, D., Hebl, M., Guerra, R., Osherson, D., & Zimmer, H. (2003). Introduction to statistics. Center for Open Education/University of Minnesota’s College of Education and Human Development. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/459

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Sage.

Robert, A. (2019, April 16). Law libraries chart a new direction for the future, new report shows. ABA Journal, https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/law-libraries-chart-new-direction-for-the-future-aall-report-shows

Ryan, S. E. (2013). Data, statistics, or secondary statistical analysis: Helping students articulate and acquire the numbers they’re (really) seeking. Perspectives: Teaching Legal Research and Writing, 22(1), 30-34.

Ryan, S. E. (2015). Teaching empirical legal research study design: Topics & resources. Perspectives: Teaching Legal Research and Writing, 23(2), 152-57.

Ryan, S. E. (2016). Human subjects research review: Scholarly needs and service opportunities. Law Library Journal, 108(4),579-98.

Ryan, S. E., Hebdon, C., & Dafoe, J. (2014). Energy research and the contributions of the social sciences: A contemporary examination. Energy Research & Social Science, 3, 186-97.

Ryan, S. E., Hong, L., & Rashid, M. (forthcoming). From corpus creation to formative discovery: The power of big data-rhetoric teams and methods. Review of Communication.

Ryan, S. E., Rashid, M. & Ali, I. (under review). Data-driven empirical research costing: Using scholarly literature, open government data, and formative case studies to plan projects.

Sachs, J. D. (2020). The ages of globalization: Geography, technology, and institutions. Columbia University Press.

Sanyal, D. K., Bhowmick, P. K., Das, P. P., Chattopadhyay, S., & Santosh, T. Y. S. S. (2019). Enhancing access to scholarly publications with surrogate resources. Scientometrics, 121(2), 1129-1164.

Tracy, M., Braga, A. A., & Papachristos, A. V. (2016). The transmission of gun and other weapon-involved violence within social networks. Epidemiologic Reviews, 38(1), 70-86.

Tucker, V. M., & Lampson, M. (2018). Finding the answers to legal questions. ALA Neal-Schuman.

van den Bos, K., & Hulst, L. (2016). On experiments in empirical legal research. Law and Method [blog], https://www.lawandmethod.nl/tijdschrift/lawandmethod/2016/03/lawandmethod-D-15-00006

Whisner, M. (2003). Practicing reference . . . Researching outside the box. Law Library Journal, 95(3), 467-73.

Whisner, M. (2016). Practicing reference . . . Data, data, data. Law Library Journal, 108(2), 313-19.

Wollaston, A. F. R. (1912). Pygmies and Papuans: The stone age to-day in Dutch New Guinea. William Clowes and Sons, Limited.