1 Historical Roots of Empirical Legal Studies

Empirical Legal Studies is the product of several histories. Mid-nineteenth century U.S. legal instruction and practice paved the way for law as an academic discipline. Late nineteenth century development of social science departments gave law faculty access to university infrastructure and interdisciplinary colleagues. Early twentieth century experiments in law and social science paved the way for research subfields such as law and economics, empirical legal studies, new legal realism, and law and social science. Many refer to these recent traditions collectively, as Empirical Legal Studies, empirical legal studies, or ELS, though this labelling is a source of debate.

Understanding these histories is important for three reasons. First, the histories point us to primary source research material such as the Litchfield notebooks, which were written by law students at one of the nation’s early law schools and digitized for research by twenty-first century law librarians (Eiseman, Bagnall, Kellett, & Lam, 2016). Second, the histories explain the dominance of certain social scientific disciplines and methods in past and current empirical legal studies. Finally, the histories of empirical legal studies enable us to predict the future of the field.

Chapter learning objectives

- Understand the early history of U.S. legal practice and instruction

- Analyze the interdisciplinary roots of empirical legal research

- Evaluate the influence of historical practices on current legal research and teaching

- Create historical research aids

Abbreviations and specialized terms

American Association of Law Libraries (AALL), Annual Law and Economics Review, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, case law, Conference on Empirical Legal Studies (CELS), clerk, content analysis, de facto, de jure, empirical legal studies, Inns of Court, IPUMS, Jurimetrics, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (JELS), Law and Human Behavior, law and social science, Law & Society Review, Law Library Journal, legal realism, natural sciences, new legal realism, pragmatism, qualitative coding, Society for Empirical Legal Studies (SELS), social sciences, statutes

Early Legal Education and U.S. Law

United States legal instruction developed slowly. The colonial colleges offered no practical training in law (Klafter, 1993). So, wealthy young men went to Britain, attended Inns of Court, and applied to become English barristers (Lucas, 1974; Klafter, 1993). As trainees, they observed court proceedings and read barristers’ books and legal notes (Lucas, 1974). This pathway to practice was reserved for affluent, well-connected families. Following the U.S. revolution, these students began to train closer to home.

By the late 1700s, most new attorneys were self-taught practitioners that studied state statutes, or laws created by legislatures, in preparation for admission to the state bar (Klafter, 1993). Many served as apprentices, or law clerks, to practicing attorneys and judges. Clerkships were often unstructured, menial, and inadequate (Klafter, 1993). To fill the gap, prominent attorneys and judges began to launch private training programs.

Beginning in the late 1700s in Connecticut and surrounding states, aspiring attorneys could enroll in private classes (Forgeus, 1939). Many of these classes took place in law offices. The Litchfield law school, founded by Tapping Reeve and known for decades as Judge Reeve’s School, is widely considered the earliest formal training program, though a number of others opened soon after (Forgeus, 1939, 1942).

The early law schools typically had classes of a dozen or fewer students. Judge Reeve’s school was especially popular, though, and had 50 students around 1810 (Forgeus, 1942). Law students often hailed from prominent families, attended Ivy League undergraduate institutions, and went on to notable positions in government and industry (Forgeus, 1939, 1942, 1946). They kept notebooks that they recited from and corrected to master their assigned subjects.

By the early 1800s, the private training programs began developing formal curricula. A student notebook, circa 1811-13, from Sylvester Gilbert’s law school in Hebron, Connecticut lists a program of study focused on common legal issues such as mortgages, legal writing (e.g., pleadings), and legal practice in Connecticut state (Forgeus, 1942; Figure 1.1).

1.1 Edited excerpt of Gilbert curriculum (Forgeus, 1942, p. 201)

| Federal Courts | Courts of Connecticut | Courts of the U.S. & Other States | Natural Law |

| Municipal Law | Common and Statute Law | Penal Statutes | Sheriffs (4 lectures) |

| Master and Servant (6 lectures) | Baron and Feme (8 lectures) | Incorporeal Hereditaments | Mortgages (6 lectures) |

| Descents (4 lectures) | Executors & Administrators (8 lectures) | Action of Trover | Action of Covenant (2 lectures) |

| Action of Assumpsit (3 lectures) | Action of Ejectment (2 lectures) | Trespass (4 lectures) | Nuisances (2 lectures) |

| Pleas and Pleadings (19 lectures) | New Trials (3 lectures) |

Gilbert and other instructors utilized legal treatises, such as Kirby, Root, and Day’s collection of Connecticut cases or Swift’s treatise on Evidence (Fernandez, 2012; Forgeus, 1939, 1942). Still, their lectures focused on English cases (Forgeus, 1942) and the old country principles the instructors knew best (Klafter, 1993). As a result, the private training programs offered a regressive legal education that failed to fully prepare students in emerging U.S. laws and legal customs (Klafter, 1993).

1.2 Law Librarian Spotlight: Elizabeth Forgeus

From the mid-1930s to late 1940s, Elizabeth Forgeus published numerous articles on law school history. Rich with passages and lists extracted from student letters and notebooks, her pithy articles humanized the early law schools. She also assisted with longer research works on the history of Yale Law School and legal practice in New England. Serving as Assistant Law Librarian at the Yale Law School for more than a decade, Ms. Forgeus was also active in the American Association of Law Libraries (AALL). Past issues of AALL’s flagship publication, Law Library Journal, list Ms. Forgeus as a member of the Committee on Cooperation with Latin-American Law Libraries and the Advisory Committee on Education for Law Librarianship—Editorial Board on Monographs. Her work demonstrated the value of reference librarianship, archival collecting, international outreach, and educational advocacy in law libraries.

By the mid-nineteenth century, private law programs gave way to academic law schools. The College of William and Mary and Transylvania College offered the first vocational legal instruction (Klafter, 1993). Harvard, the University of Maryland, Washington and Lee, Yale and others followed (Klafter, 1993). Despite the growing number of academic law programs, university legal instruction remained in flux for decades, in part due to a dearth of textbooks.

In 1870, Christopher Columbus Langdell joined the Harvard Law faculty. The next year, he published a Contracts casebook for use in his classes. In the preface, Langdell explained that most law students accessed books through the library and had no lasting copies of the cases they read (1871). He felt that reported cases were the best evidence of how the law was developing and that students needed to rigorously analyze case law to learn the principles and doctrines, or science as he called it, of U.S. law (1871).

Langdell’s approach was treatise-based and deductive. This view of legal education—and legal practice—was a hallmark of the era known as the classical period, or era of legal formalism (Hackney, 2014). Langdell’s Contracts casebook encouraged students to deduce general rules from existing cases. This case law method is still the most common form of teaching in first-year law school courses.

Langdell’s casebook is an artifact of a larger debate over legal formalism in the early twentieth century. Legal formalism posited law as apolitical or a priori to social concerns (Hackney, 2014). Believing that law should exist outside of messy social situations, many experts recommended contracts as a way to deal with complex social issues such as unfair working conditions and environmental pollution (Hackney, 2014). The Lochner case is now taught as quintessential formalism.

1.3 Legal Touchstone: Lochner v. New York

In 1905, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Lochner v. New York, finding that a New York state employment law was unconstitutional. The law prohibited bakeries from allowing their employees to work more than 60 hours a week or 10 hours a day, with some exceptions. In a five-justice majority opinion written by Justice Peckham, the Supreme Court found that the state statute interfered with employees’ contract rights under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Justice Harlan wrote a dissent, which was joined by Justices White and Day, that discussed workers’ health and argued that the government could legislate to protect the health of citizens. Justice Holmes also dissented and argued that Lochner was “decided upon an economic theory [laissez-faire] which a large part of the country [did] not entertain” (p. 75) The Lochner majority opinion represented the formalist position that the law is generally set apart from concerns of health and economics (Hackney, 2014). The dissents reflected a growing trend toward viewing the law as embedded in social relations.

Today, scholars and practitioners actively debate the law’s relation to society (Suchman & Mertz, 2010). In fact, empirical legal studies can be understood in opposition to formalism because ELS explores how the law can cause or ameliorate social problems. But despite the widespread acceptance of empirical legal studies as a valid research field, the empirical approach has been slow to infuse law school curriculum. First year law students still largely dissect cases presented in Langdell-style casebooks; they do not study how real people interpret liability waivers or rental contracts, etc. So, law school instruction focuses on formal rules while empirical legal studies research explores law in social context.

Research that examines how the law treats various classes of plaintiffs or improves the function of government, etc. requires more than a social orientation. It requires social science theories and research methodologies. It is no surprise, then, that empirical legal research followed the rise of modern social science departments in the United States.

Development of U.S. Social Science Departments

Prior to the 1840s, U.S. colleges generally taught a classics curriculum—Latin, Greek, mathematics, literature, and rhetoric—derived from leading Western European universities (Geiger, 2000; Thomas, 2015). By the mid-1800s, this standard curriculum began to vary across institutions and regions of the country (Geiger, 2000). Institutions such as the Lander College for women in South Carolina featured the classical A.B. degree into the twentieth century, whereas colleges throughout the state of Ohio began moving away from the curriculum decades earlier (Bondurant, 1909; Geiger, 2000). Overall, the traditional classics degree declined nationally as multipurpose colleges began to take shape (Geiger, 2000). Multipurpose colleges enrolled a more diverse student body, including women and lower class students, and responded to “emerging markets for practical, vocational skills” (Geiger, 2000, p. 148).

1.4 Understanding early U.S. college admissions trends through scholarly literature and government data

The multipurpose colleges were more diverse than the colleges that preceded them, but their student bodies were still largely White and upper class. Most nineteenth century colleges did not admit Black students and many had de jure (by policy or law) or de facto (in practice) admissions policies that limited the attendance of Asian, Latino, Jewish, and Native American students. Empirical researchers can explore scholarly literature on college admissions via a literature search. For instance, the following search string should produce useful results in EBSCOhost: ((college OR university) AND admiss* AND (historic* OR “nineteenth century”) AND (race OR gender OR Black OR “African American” OR Asian OR Hispanic OR Jewish OR Latino OR “Native American”)). For demographic context, the U.S. Census Bureau maintains historical publication series. The Minnesota Population Center lists the Census questionnaires from 1850 forward on its IPUMS, or Census microdata, site at https://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/tEnumForm.shtml. The Census questionnaires offer a glimpse into the evolving language of racial and ethnic identity—and exclusion—in the U.S.

In 1862 and 1890, Congress passed the Morrill Acts (Geiger, 2000). The Morrill Acts gave federal lands to states for the creation of local colleges focused on “agriculture and the mechanic arts” (Morrill Act of 1862). The new laws furthered an existing system of publicly-supported colleges—including tax-supported private colleges like Harvard and Yale (Thomas, 2015)—but emphasized the vocational role of land-grant institutions. As a result, U.S. colleges became more attuned to local industries and interests than their Western European counterparts (Thomas, 2015). But though U.S. colleges were becoming more pragmatically focused, they were not yet incubators of scientific discovery or rigorous social science research.

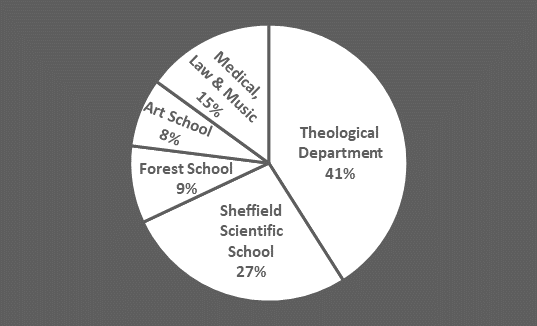

A number of factors slowed the development of scientific and social scientific research in U.S. colleges. Most U.S. colleges had “serious religious commitments,” and formalistic theological instruction permeated the curricula until well after the Civil War (Veysey, 1965). For instance, more than 40% of Yale University’s 1900 budget supported the Theological Department (Treasurer of Yale University, 1900; 1.5).

1.5 Yale University departmental budget allotments, 1900

Nineteenth century U.S. colleges, unlike their Scottish counterparts, had no track record of scientific excellence, and no community of science researchers or educators (Ben-David, 1992). When reformers at Cornell and Harvard wanted to increase scientific research and teaching in the late 1800s, they struggled to find competent teachers and a place in the undergraduate curriculum for such courses (Ben-David, 1992). As a result, reformers shifted their attention to the creation of graduate schools at existing colleges.

Once graduate schools began producing rigorously trained academics, those scholars were able to modernize both research and undergraduate instruction in the sciences and social sciences (Ben-David, 1992). At that point, the U.S. system again diverged from much of Western Europe, where “first-rate scholars were not willing to teach courses in a program of general education” (Ben-David, 1992, p. 83). In the U.S., top-tier researchers conducted research, employed graduate students, and taught undergraduate students in university departments dedicated to the natural and social sciences. Their research built upon the work of European and U.S. scholars.

European pioneers of the social sciences included Adam Smith, Marie Jean Antoine Condorcet, and Johann Gottfried Herder (Ross, 1993). In the U.S., notable figures included Harvard’s William James and the University of Chicago’s John Dewey (Buxton, 1984; Thayer, 1982), not to be confused with Columbia University’s library science educator, Melvil Dewey. James and John Dewey led the development of pragmatism, a U.S.-born philosophical tradition that emphasized the value of grounded theories of people and the social world (Misak, 2013; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Dewey’s view of pragmatism, like much early U.S. social science, hewed to natural science methods (Misak, 2013; Ross, 1993). According to historian Dorothy Ross, the U.S. social sciences were generally less heterogeneous and more derivative of the natural sciences than their European counterparts (1993). Throughout the twentieth century, Economics increasingly dominated the U.S. social sciences (Haskell, 1977; Siegfried, 2008). As evidence: the American Social Science Association, founded in late 1800s, now operates as a subset of the American Economic Association (see Haskell, 1977; Siegfried, 2008). The unique trajectory of the U.S. social sciences as empirical, experimental, and economics-dominated set the stage for the empirical legal research movements of the twentieth century.

1.6 Notes from the Desk of Sarah E. Ryan: My empirical research on the 'facebook'

In 2012, Yale Law School hired me as the nation’s first dedicated empirical legal research librarian (Miguel-Stearns & Ryan, 2014; Ryan & Miguel-Sterns, 2014). So, I had to build the new service area. My biggest issue was that I did not know where my patrons—especially the students—were starting from. Were they continental philosophers? Economists? Mechanical engineers? I mulled the idea as I began to take appointments. To prepare for one reference meeting, I looked up the patron in our print “facebook,” which contained a picture of each student, faculty, and staff member as well as students’ prior degrees. It dawned on me that the “facebook” was a data source and that mining it would be an interesting content analysis, or coding, project. For the “facebook” project, my chief aim was efficiency, so I adopted a binary (0/1) code for social science degree (i.e., either the student had a social science degree or didn’t). However, I quickly saw that colleges award a dizzying array of degrees, many of which are interdisciplinary. Further, I realized that I had never given much thought to what divides the humanities from the social sciences and the social sciences from the natural sciences. So, I reviewed the websites of prominent universities and kept a tally of what they counted as social sciences (Ryan, 2013). I then used a spreadsheet as my coding instrument and followed a simple rule: “students with degrees in six key social science fields would receive a one rather than a zero in the degree columns” (Ryan, 2013). The project yielded a useful statistic: more than 70% of Yale law students held a social science degree (Ryan, 2013). The empirical research was a fun way get to know my patrons, organize my work, and earn a first publication in law librarianship.

Legal Realism: The First Attempt to Merge Legal Research And Social Sciences

As the social sciences gained prominence in academia, legal scholarship began to move beyond formalism. While formalists championed the scientific application of context-neutral law, a new group of thinkers challenged the deductive, apolitical view of legal practice and justice. The legal realists of the early twentieth century adopted a contextual vision of the law and legal training (Hackney, 2016). In an effort to predict how judges and bureaucrats would enact law, for instance, realists studied their decision-making (Schlegal, 1980). Realists grounded this work in logic, philosophy, psychoanalysis, and scientific management theory (Cohen, 1923), and engaged with theorists outside of the law school. Underhill Moore, a realist concerned with how bankers assess risk (Moore & Hope, 1929), was encouraged to pursue his law-in-action research by leading social scientists of the day, including John Dewey (Schlegal, 1980). By the 1930s, dozens of scholars were conducting realist studies (Llewellyn, 1930; Hull, 1987). John Hopkins University launched an Institute of Law to foster realist research (John Hopkins University, 1929). But before long, the realists faced challenges from across their universities.

The realist movement coalesced around the New Deal and boasted prominent legal scholars (Suchman & Mertz, 2010). But by the mid-twentieth century, the movement had all but collapsed. Social scientists criticized legal realist work as crude and devoid of guiding theory or disciplinary tradition (Schlegal). Many traditional legal scholars dismissed the realists wholesale without appreciating their aims or methods (Schlegal). From all sides, the critiques understated differences within the realist movement—e.g., scholars focused more on reform rather than social science and vice versa—and between realism and formalism (Schlegal). Most importantly, the realists had neither an established place in the university nor in the legal profession (Schlegal). Without institutional support, the realists were unable to sustain their endeavor (Schlegal; Suchman & Mertz).

But even if the realists failed in their objectives, their approach to the law was a break with tradition that had lasting impacts on legal education, practice, and research. Realists like Underhill Moore, Charles Clark, William Douglas, Karl Llewellyn, and Louis Brandeis,

secured a place for social science in the law (Suchman & Mertz). As a result, realism paved the way for Empirical Legal Studies, the Law and Society movement, and other late 20th century legal subfields.

Contemporary Empirical Legal Studies

Today, the history of legal realism is itself a cottage industry. Some monographs focus on Roscoe Pound, others on Underhill Moore, and still others on Harold Lasswell and legal realists at Yale Law School. As professor Jack M. Balkin explains, “the choice of who is enshrined in the [realism] canon turns very much on the points one wants to make about the history of American law and legal education” (1998, p. 200). Similarly, the story of post-World War II empirical legal studies is contested and political.

Following World War II, law and social science projects gained steam again, most notably at the University of Chicago and Yale Law School. At Chicago, economist Ronald Coase led groundbreaking econometric studies of property law and transaction costs, and fostered a law and economics movement that survives to this day (Coase, 1993; Landes & Posner, 1993; Ho & Rubin, 2011). At Yale Law School, Underhill Moore was soon joined by Eugene Rostow, and then Boris Bittker and Guido Calebresi. Guido Calabresi produced empirical-theoretical treatises on strict liability that challenged formalism and neoclassical economics (Hackney, 2014). Calabresi’s progressive policy focus still informs descriptive and normative empirical scholarship. Elsewhere, social scientists such as Fred Kort used empirical methods to study judicial behavior and other legal topics (see Kort, 1957); their work is now seen as foundational to the field even if it was underappreciated by law professors at the time (Hall & Wright, 2008). The topical and methodological heterogeneity evidenced by Coase, Calebresi, and Kort’s work leads some scholars to view modern law and social science research as a continuation of legal realism (i.e., New Legal Realism; Suchman & Mertz, 2010). Fortunately, the broad field encompassing empirical legal studies, new legal realism, and law and social science has become more rigorous than legal realism ever was.

Until the late twentieth century, empirical legal research was an eclectic and undisciplined field. Content analysis was an early empirical research method, for instance, but most legal empiricists developed their analytic practices organically and without reference to methodological advances in fields such as Linguistics or Political Science (Hall & Wright, 2008; Suchman & Mertz, 2010). For instance, Richard A. Posner “read every published accident opinion of an American appellate court (state or federal, final or intermediate) issued in the first quarter of 1875, 1885, 1895, and 1905 . . . .” for his seminal article, A Theory of Negligence, but did not develop a codebook or utilize a content analysis instrument or employ a neutral coder to systematize and validate his findings (Posner, 1972; Hall & Wright).

Noting the need for methodological advancement, research training, and routine scholarly communication among empiricists, Theodore (Ted) Eisenberg of Cornell Law School and others founded the Society for Empirical Legal Studies (SELS), Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (JELS), and Conference on Empirical Legal Studies (CELS). Today, empirical legal researchers can present their early work at conferences featuring artificial intelligence and law, psychology and law, text analysis and law, and more. This organizing work was one of the factors in the rapid growth of empirical legal studies from the 1990s to the 2010s (Heise, 2011). So to was the development of specialized law journals. Today, law and social science scholars can publish their findings in a range of empirical research journals, including: Annual Law and Economics Review, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, Jurimetrics, Law and Human Behavior, Law & Society Review, and more. As a result, ELS offers many opportunities and resists simple classification. The field of several histories continues to branch out in many directions.

Reflection Questions

- Prior to reading this chapter, what was your impression of how U.S. legal instruction developed? Has that changed? If so, how? If not, which facts or ideas in this chapter reinforced your existing beliefs?

- Do you agree or disagree with the chapter’s premise that Economics has long dominated the social sciences in the U.S.? Explain. If you were educated in a non-U.S. country, which perspectives seem to dominate the social sciences in that country(ies)?

- Pragmatism played a key role in the development of the U.S. social sciences. How might pragmatism affect legal researchers’ choice of research subjects or methods today?

- How might you display historical information in this chapter visually (e.g., in presentation slides)?

References

Balkin, J. (1998). John Henry Schlegel, American Legal Realism and Empirical Social Science, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995 [book review]. Law and History Review, 16(1), 199-201.

Ben-David, J. (1992). Centers of learning: Britain, France, German, United States. Routledge.

Bondurant, B. C. (1909). The status of the classics in the South. The Classical Journal, 5(2), 59-67.

Buxton, M. (1984). The influence of William James on John Dewey’s early work. Journal of the History of Ideas, 45(3), 451-463.

Coase, R. H. (1993). Law and economics at Chicago. Journal of Law and Economics, 36(1), 239-254.

Cohen, M. R. (1923). On the logic of fiction. The Journal of Philosophy, 20(18), 477-488.

Eiseman, J., Bagnall, W., Kellett, C. & Lam, C. (2016). Litchfield unbound: Unlocking legal history with metadata, digitization, and digital tools. Law and History Review, 34(4), 831-855.

Fernandez, A. (2012). Tapping Reeve, coverture and America’s first legal treatise. In A.Fernandez & M. D. Dubber (Eds.), Law books in action: Essays on the Anglo-American legal treatise (pp. 63-81). Hart Publishing.

Forgeus, E. (1939). Letters concerning some Litchfield Law School notebooks. Law Library Journal, 32(5), 201-05.

Forgeus, E. (1942). An early Connecticut law school: Sylvester Gilbert’s school at Hebron. Law Library Journal, 35(4), 200-03.

Forgeus, E. (1946). Sylvester Gilbert’s law school at Hebron, Connecticut: The students. Law Library Journal, 39(2), 49-52.

Geiger, R. L. (2000). The era of the multipurpose colleges in American higher education. In R. Geiger (Ed.), The American college in the nineteenth century (pp. 127-152). Vanderbilt University Press.

Hackney, J.R., Jr. (2014). Guido Calabresi and the construction of contemporary American legal theory. Law and Contemporary Problems, 77(1), 45-64.

Hall, M. A., & Wright, R. F. (2008). Systematic content analysis of judicial opinions. California Law Review, 96(1), 63-122.

Haskell, J. L. (1977). The emergence of professional social science: The American Social Science Association and the nineteenth-century crisis of authority. University of Illinois Press.

Heise, M. (2011). An empirical analysis of empirical legal scholarship production, 1990-2009. University of Illinois Law Review, 2011(5), 1739-1752.

Ho, D. E., & Rubin, D. B. (2011). Credible causal inference for empirical legal studies. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 7, 17-40.

Hull, N. E. (1987). Some realism about the Llewellyn-Pound exchange over realism: The newly uncovered private correspondence, 1927-1931. Wisconsin Law Review, 1987(6), 921-969.

John Hopkins University. (1929). The story of the Institute of Law at the John Hopkins University. Norman T.A. Munder & Co.

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905).

Klafter, C. E. (1993). The influence of vocational law schools on the origins of American legal thought, 1779-1829. The American Journal of Legal History, 37(3), 307-31.

Kort, F. (1957). Predicting Supreme Court decisions mathematically: A quantitative analysis of the “right to counsel” cases. American Political Science Review, 51(1), 1-12.

Landes, W. M., & Posner, R. A. (1993). The influence of economics on law: A quantitative study. The journal of law and economics, 36(1, Part 2), 385-424.

Langdell, C. C. (1871). A selection of cases on the law of contracts: With references and citations. Harvard Law School.

Llewellyn, K. N. (1930). A realistic jurisprudence –The next step. Columbia Law Review, 30(4), 431-465.

Miguel-Stearns, T., & Ryan, S. E. (2014). The empirical research law librarian. Part 1: Making the case and filling the role. Trends in Law Library Management and Technology, 24, 1-6.

Misak, C. (2013). Rorty, pragmatism, and analytic philosophy. Humanities, 2(3), 369-83.

Moore, U., & Hope, T. (1929). An institutional approach to the law of commercial banking. Yale Law Journal, 38(6), 703-19.

Morrill Act of 1862. (2012). Codified at 7 U.S.C. § 301 et seq.

Posner, R. A. (1972). A theory of negligence. The Journal of Legal Studies, 1(1), 29-96.

Ross, D. (1993). An historian’s view of American social science. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 29(2), 99-112.

Ryan, S. E. (2013, June). Digging in to patron data: What I learned from the law school “facebook.” AALL Spectrum, 20-21.

Ryan, S. E., & Miguel-Stearns, T. (2014). The empirical research law librarian Part 2: Developing the role. Trends in Law Library Management and Technology, 24, 7-12.

Schlegel, J. H. (1980). American legal realism and empirical social science: The singular case of Underhill Moore. Buffalo Law Review, 29(2), 195-323.

Siegfried, J. J. (2008). History of the meetings of the Allied Social Science Associations since World War II. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67(5), 973-84.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Pragmatism. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pragmatism/

Suchman, M.C. & Mertz, E. (2010). Toward a new legal empiricism: Empirical legal studies and new legal realism. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 6, 555-79.

Thayer, H. S. (Ed.). (1982). Pragmatism, the classic writings: Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, Clarence Irving Lewis, John Dewey, George Herbert Mead. Hackett Publishing.

Thomas, G. (2015). The founders and the idea of a national university: Constituting the American mind. Cambridge University Press.

Treasurer of Yale University. (1900). Report of the treasurer of Yale University. Yale University.

Veysey, L. R. (1965). The emergence of the American university. University of Chicago Press.