5 Chapter 5: Digital Content Management

5.1 Introduction

Digital content refers to any type of material that exists in digital format, whether the material is born-digital or converted using scanning and digitization. Digital content has increased in recent years because of modern and innovative technologies, such as social media, enterprise applications, digital publishing, smart cities applications, Internet of Things (IoT) applications, and mobiles devices, such as smartphones with enhanced digital capture capabilities. Big data generated from e-commerce and enterprise transactional applications has sparked interest in data analysis and digital discovery tools and methods. Such increased interest has led to the emergence of new disciplines, such as data analytics and data science.

The shift from paper-based products to increasingly digital information products has also impacted the field of library and information science in terms of access and collection management. Over time, we have seen a decrease in libraries’ holdings of paper materials and, at the same time, an increase in digital content. As an example, academic libraries have done away with keeping back issues of academic journals and have increasingly moved toward subscription and digital access to electronic journals. The shift toward open access makes it easier and more affordable for libraries to provide access to curated digital collections. The role and nature of the librarian and information professional’s job are also changing. Some existing jobs are being reinvented or expanded, and many new jobs are being created.

5.2 Content is King

In 1996, Bill Gates wrote the essay titled “Content is King,” which was published on the Microsoft website. In the essay, he describes the future of the Internet as a marketplace for content. He further suggests content could serve as an equalizer because anyone could create and publish content.

One of the exciting things about the Internet is that anyone with a PC and a modem can publish whatever content they can create. In a sense, the Internet is the multimedia equivalent of the photocopier. It allows material to be duplicated at low cost, no matter the size of the audience.

The quote from “Content is King” has fast became a reality. Now content is everywhere. Everyone has easy access to user-generated content or user-created content, which is defined as: (1) content made publicly available over the Internet, (2) which reflects a certain amount of creative efforts, and (3) which is created outside of professional routines and practices” (OECD, 2011, p. 47). Recent advances in information communication technology have reduced the time, effort, and costs of creating and sharing derivative works. The popularity of social media, such as YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, has prompted the emergence of new social and cultural behaviors, where people are now empowered to become active creators. This phenomenon is called the “Read-Write culture,” sometimes Remix culture, coined by Lawrence Lessig (2008), founder of Creative Commons. A producer of remix culture is anyone who transforms a cultural object and then makes that transformation public. A consumer of remix culture is anyone who listens to, watches, reads, or plays these transformed media texts. Producers and consumers of remix now number in the millions.

5.3 Overarching Challenges of Digital Content

Digital content creation has been steadily increasing and is now booming, growing exponentially in this new world of digital transformation. As discussed in previous chapters, technological innovations have made it easy to collect and distribute digital content, so that today organizations, libraries, and individuals maintain collections of digital assets, including documents, images, audios, videos, etc. These collections are constantly growing, and ever-increasing demands are being placed on how digital content should be managed and delivered. Specifically, recent technological advances in rich media sharing have made the distribution of digital content across online social network sites easy and inexpensive. User expectations for access to digital content have increased exponentially as well. This proliferation of digital content in the networked digital environment poses challenges and opportunities.

The initial problem with digital content management was the content itself. Digital content encompasses a vast array of born digital or digitally stored information, including images, video, audio, games, websites, blogs and wikis, online ads, online news, and more (Reyna et al., 2017). In terms of the content of digital archives and repositories, types of digital content also include digitized legacy content, such as scanned and digitized historical documents or converted VHS tapes to MPEG4 files; born digital art and/or electronic literature; research datasets; and learning objects (Simons and Richardson, 2013). Digital content exists in several forms and types. Therefore, we cannot apply the simple and straightforward process implemented in the analog world that involves transforming static objects, such as printed documents and other artifacts, into various forms of digital content. For example, websites have links that not only change but also point to dynamically changing sites. Internet users are all familiar with the link failure syndrome—“page not found.”

Another challenge is the fact that this growth exceeds the available storage space. The voluminous nature of digital content and technological limitations of storage technology have led to a gap between storage demand and supply. Further, while digital storage has become cheaper, the associated costs have not kept up with the proliferation of digital content. International Data Corporation (IDC) recently published its annual DataSphere and StorageSphere forecasts, which measure the amount of data created, consumed, and stored in the world each year. They predict that global data creation and replication will experience a compound annual growth rate of 23% over the forecast period, leaping to 181 zettabytes in 2025. While this report took a top–down appraisal of the creation of all digital content, much of this data might never be stored or will be retained for only a brief time. Data stored for longer retention, furthermore, is frequently compressed. The report also noted that the “stored” digital universe is, therefore, a smaller subset of the entire digital universe as projected by IDC (Rydning and Reinsel, 2021).

Technological obsolescence, which results from the evolution of technology, is considered the greatest technical threat to ensuring continued access to digital content. Digital content is often dependent on the technical environment. They are fragile because they require various layers of technological mediation before being heard, seen, or understood by people. But those mediation tools will not be usable forever. Hardware and software become obsolete at differing speeds, potentially leaving digital contents unstable or unreadable over time. Hardware and software obsolescence is costly because as systems age, the costs to operate and maintain them go up (Jenab et al., 2014). Additionally, file format obsolescence is one of the main threats to the longevity of digital content. New file formats have emerged. Files must be migrated or emulated as they become obsolete to ensure that they can still be rendered and used in the future. For preservation and storage, the Library of Congress (2020–2021) specifies preferred formats for archiving digital content. These are shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Summary: LOC Recommended Formats for Digital Content Preservation

|

Digital Content Type |

Preferred Format |

Acceptable Format |

|

Textual |

XML, PDF/UA |

HTML, SGML, RTF |

|

Images |

TIFF, JPEG2000, PNG, JPG |

DNG, GIFF |

|

Video |

IMF, MPEG-2 |

MPEG-4 |

|

Audio |

WAVE, DSD |

|

|

Musical scores |

MusicXML, MEI |

HTML, SGML, PDF |

|

Datasets |

TSV, CSV |

CDF, HDF |

|

GIS/Non-GIS images |

Shapefile, Esri File, GeoTIFF |

GML, TIFF, Geospatial PDF |

|

Design and 3D |

TIFF, JPEG2000, PNG |

Photoshop |

|

Software and video games |

Uncompiled Source Code |

Flash drive |

|

Web archives |

WARC |

ARC IA |

5.4 Digital Content Lifecycle Model

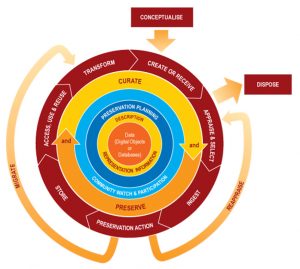

As shown in Figure 5.1, the Curation Lifecycle Model proposed by the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) offers a high-level graphical overview of the lifecycle stages required for successful curation. One of the model’s creators explained that “the DCC’s own theoretical construct was a lifecycle model which provided an organizational matrix for developing their research, planning, advisory and training activities” (Higgins, 2008, p. 1327). The graphic developed by DCC utilizes four matrixed layers of actions, eight sequential actions, and occasional actions, and focuses heavily on “upstream point-of-creation activities” regarding digital content preserved and curated (Huang et al., 2020, p. 3).

Constantopoulos and his colleagues (2009) proposed the extended lifecycle model to support the planning and organization of digital content management by pinpointing important curation activities not included in the DCC model. The revised model adds user experience as a sequential action and augments description and representation information also to cover maintaining authorities—information regarding the main entities, concepts, and relations. It also extends the curate and preserve cycle to include knowledge enhancement, which is new knowledge generated through research and practice encoded and organized in annotations, rules, or ontologies.

5.5 Historical Development and Trends in Digital Content Management

5.5.1 Content Management Solutions

Digital content management solutions are needed to facilitate the access, sharing, and reuse of content in knowledge-intensive environments that must handle an increasing volume of data and information (Venkitachalam and Bosua, 2019). One solution is found in the enterprise content management (ECM) system. ECM is defined as the tools, processes, strategies, and skills required to manage an organization’s information assets over its lifecycle (Hullavarad et al., 2015). Unlike other content management solutions, ECM can manage all the information assets for an organization, including reports, spreadsheets, web pages, office documents, images, audio, video, and more (Dammak and Gardoni, 2018). ECM systems consist of four primary components: (1) user interface, (2) information governance, (3) attributes, and (4) repository. The user interface is the entry point by which digital information is brought into the system. After content enters the ECM system, it becomes official, making it subject to information governance, that is, the rules and regulations that specify record duration and retention. In this way, information governance sets the ECM system apart from other types of digital archiving systems. The third component of the ECM system, attributes, comprises the features that allow the ECM to achieve its mission and vision, including data archiving, integration, and data processing, data capture, workflow process, and information disposal. Finally, the repository component creates a secure method for storing digital content, either on-site or in the cloud (Hullavarad et al., 2015).

However, a dedicated digital content management system (DCMS) is seen with the likes of WordPress, which serves as a platform for both the creation and publication of digital content, from static websites to blogs to forums to online stores. Holding the largest market share among its competitors, WordPress powers approximately 30% of all websites. Similar platforms with lower market share include Joomla, Drupal, and Squarespace (Cabot, 2018). A hybrid of the DCMS and the ECM system is seen in the learning content management system (LCMS). Unlike the learning management system (LMS), which exists independently of course content, LCMSs also function as learning content repositories (Petrov et al., 2019). They offer more sophisticated authoring applications than LMSs and are more suitable for instructional design and development than an LMS alone. Moodle is just one example of an LCMS. Another method of combining LMS and CMS capabilities is using an LMS plug-in with a CMS. An example of this is the LearnDash plug-in, which integrates with WordPress (Lynch, 2020).

5.5.2 Digital Libraries

Although digital libraries are now ubiquitous, the visions of digital libraries appeared decades ago. Vannevar Bush’s vision of Memex first inspired the digital libraries initiative:

a device in which an individual stores all his books, records and communications which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility (Linde, 2006).

The 1990s marked an important decade in the development of digital libraries.

Various communities, including funders, technology-focused researchers, and library practitioners, responded to the opportunities offered by emerging networked computing technologies. The term “digital library” was first popularized in 1994 when the Digital Libraries Initiative (DLI), a federal interagency program sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF), Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), and National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA), was launched. Around the globe, hundreds of millions of dollars were spent on developing the infrastructure in those five years for what we now call digital libraries or digital collections. In its second phase, called DLI-2 (1999–2004), which focused more on collections building, upward of $48 million was awarded, with research aimed at use and users as well as cyber-infrastructure (Griffin, 2005).

After DLI-1 and DLI-2, several digitization projects were undertaken. The first IMLS-funded digitization project was initiated in 1998. In fact, text digitization in the cultural heritage sector started in 1971 when Project Gutenberg first sent the text of the United States Declaration of Independence across electronic networks. Project Gutenberg’s collection primarily comprises English literature published before 1923, for which copyright has expired. This ambitious project provides thousands of classic full-text books for free. The project has expanded into dozens of languages and several formats, including audiobooks, recorded music, sheet music, still pictures, and video.

The Library of Congress (LC) has long pioneered digitization as a function of its preservation efforts. From 1989 to 1994, LC’s American Memory pilot program reproduced selected collections on American history and culture for national dissemination in computerized form. The initial distribution of the project content was by CD-ROM to select American schools and libraries. In the final year of the pilot, advantage was taken of the World Wide Web. In June 1994, three American Memory collections, all consisting of photographs, were made available over the Internet. The following year LC launched the National Digital Library Program (1995–2000), which digitized selected collections of Library of Congress archival materials that chronicle the nation’s rich cultural heritage, making them freely available on the Internet. In December 2000, the US Congress also mandated LC to take a leadership role in forming the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program, a network of institutional partners working to build a digital preservation architecture for collecting, preserving, and making accessible material only available in digital form.

Large-scale digitization initiatives were undertaken by various knowledge organizations and cultural heritage institutions. Google co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page envisioned a world in which vast collections of books would be digitized and where people would use a web crawler to index the books’ content and analyze the connections between them. In December 2004, Google announced its Library Project (also known as Google Book Search), which entailed digitizing, indexing, and displaying “snippets” of print books in the collections of five major libraries, among other things. The project included partnerships with several high-profile universities and public libraries, including the University of Michigan, Harvard University, Stanford University, the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, and The New York Public Library.

With Google scanning millions of books from the collections of research libraries, an inevitable question arose: What will happen to the scanned collections of the Google Books library partners if Google disappears? (Eichenlaub, 2013) In 2008, HathiTrust was introduced to the public as a shared digital repository jointly launched by the 12 university consortium known as the Committee on Institutional Cooperation and the 11 university libraries of the University of California System. The goal is to build a comprehensive archive of published literature from around the world available in the public domain through a digital library. HathiTrust has pursued this goal by digitizing materials like books and journals from major library collections and other partners, such as Google, the Internet Archive, and Microsoft.

Conceived by Robert Darnton of Harvard University, in part as a response to the more commercial Google Books endeavor, the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) was launched in April 2013 to build a national digital library to collocate the metadata of millions of publicly accessible digital assets. DPLA aims to create a portal for digital collections of America’s libraries, archives, and museums. Today over 44 million images, texts, videos, and sounds are discoverable in DPLA.

5.5.3 Web Archiving

In response to the challenges of persistent access to web content, web archives were created to preserve the web’s history and provide a permanent record for future access. Web archiving is defined as the process of creating an archival copy of a website. An archived site is a snapshot of how the original site looked at a particular point in time. The archive contains as much as possible from the original site, including text, images, audio, videos, and PDFs. These web archives range from home-brewed collections to large-scale archiving efforts.

The history of web archives goes back to 1996, when Brewster Kahle founded the Internet Archive (https://archive.org) with the mission of creating a universally accessible digital library. As its website states, the Internet Archive works “to prevent the Internet—a new medium with major historical significance—and other ‘born-digital’ materials from disappearing into the past” (Internet Archive, n.d.). To achieve this goal, the Internet Archive periodically takes snapshots of the entire WWW and stores copies of the captured sites in massive storage warehouses. Users can then access these websites using the Wayback Machine, a special piece of software developed by the Internet Archive. Following in the footsteps of the Internet Archive, many organizations launched web archiving programs of their own. In 1996, the National Library of Australia inaugurated the first-ever web archiving program by a national library, an effort to capture portions of Australia’s national domain and other web resources deemed significant to Australia’s history and culture (https://webarchive.nla.gov.au). In 2000, the Library of Congress established a pilot web archiving project, originally called MINERVA (Mapping the Internet Electronic Resources Virtual Archive), an effort aimed at creating topical collections of materials relevant to American history and culture. In 2003, the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC) was founded with the mission of “improving the tools, standards and best practices of web archiving while promoting international collaboration, broad access and use of web archives for research and cultural heritage.”

In 2017, the National Digital Stewardship Alliance surveyed web archiving practices in the United States. They found over 100 American institutions with web archiving programs in place: 61% were colleges and universities; 14% were federal, state, and local governments; 13% were public libraries; and the rest were organizations, such as private companies, historical associations, and museums. Of the respondents, 81% had formal web archiving programs, and the rest had programs that were either being planned or already in the pilot stage (Farrell et al., 2018).

5.5.4 Open Educational Resources

Open-educational resources (OERs) is a broad title given to educational resources in any medium available digitally, either for free or under a license that allows no-cost access, use, adaptation, and redistribution by others without or with limited restrictions. According to Walz (2015), “Open Educational Resources (OER) are built on two convictions: that ‘knowledge is a public good’ and that ‘the internet is a good way of sharing knowledge’” (p. 23). Reed and Jahre (2019) debated that the concept of OER is still in the process of being universally defined but state that most institutions use the definition by the Hewlett Foundation:

Open Educational Resources are teaching, learning, and research materials in any medium—digital or otherwise—that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaption and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions (p. 234).

Alongside how OERs are defined, the concept of open permissions used within OERs is often debated on what is required in those permissions. Miller and Homol (2016) stated the “four Rs of open content,” which outline authored works that are licensed to permit educators to Reuse—Use the work verbatim; Rework—Alter or transform the work so that it better meets the user’s needs; Remix—Combine the (verbatim or altered) work with other works to better meet the user’s needs; and Redistribute—Share the verbatim work, the reworked work, or remixed work with others. Salem (2017) stated that the common understanding of OER is the open nature of the resources, and that the obvious benefit to OER adoption over increased access to licensed content is the long term and universal access to the resources, particularly for those institutions for which OER creation or adaption is supported as part of the local initiative.

The use of OERs presents opportunities to libraries and librarians, having librarians taking the role of being involved in the presentation and discovery of OERs and the creation of OERs. Stafford (2020) suggested that institutions expressing interest in OERs should understand what their primary audience will be most interested in before beginning, and that involving faculty who choose textbooks and other course materials for their classes will be critical to the success of OER and its promotion. In the case of academic libraries, partnerships with institutional repositories have been a common approach over the last decade (Ferguson, 2017). For academic libraries and their institutions supporting local OER development, resources can be added to the institutional repository or more specialized repositories focused on teaching and learning.

5.6 Conclusion

As the world has moved online, digital content has become more important than ever and managing digital content is increasing in importance. The proliferation of digital media, web, and social networking technologies has enabled us to produce, publish, and share digital content easily. Such a vast amount of content needs to be collected, organized, and preserved to ensure that our digital contents and the information they carry remain available for future use.

This chapter presents both historical and contextual background on managing digital content. The chapter discusses the needs of digital content management, such as the proliferation of digital content and technological obsolescence, and historical development and trends in digital content management solutions, including content management solutions, digital libraries, web archiving, and open educational resources.

Discussion Questions

- Discuss the various stages of a document’s life cycle. How does that relate to content management?

- How do you define digital libraries? Have you used one before? Describe your experience.

- Compare some web content management systems (e.g., Drupal, WordPress, Joomla) and report on the key features shared among these systems.

- Discuss your experience with using web archiving. If you have not used web archiving before. Locate a web archive and describe your experience.

- What are the digital objects typically included in a digital content system?

- What are the benefits of using OER from a student perspective?

- Are you familiar with ECM or enterprise content management? Does your organization use one? Describe your experience using it.

- Locate your organization website on the Wayback machine. How far back does it exist?

References

Cabot, J. (2018). WordPress: A content management system to democratize publishing. IEEE Software, 35(3), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2018.2141016

Constantopoulos, P., Dallas, C., Androutsopoulos, I., Angelis, S., Deligiannakis, A., Gavrilis, D., Kotidis, Y., and Papatheodorou, C. (2009). DCC&U: An extended digital curation lifecycle model. International Journal of Digital Curation, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v4i1.76

Dammak, H., and Gardoni, M. (2018, July). Improving the innovation process by harnessing the usage of content management tools coupled with visualization tools. In IFIP International Conference on Product Lifecycle Management (pp. 642–655). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01614-2_59

Eichenlaub, N. (2013, November). Checking in with Google Books, HathiTrust, and the DPLA. Computers in Libraries, 33(9), 4–9.

Farrell, M., McCain, E., Praetzellis, M., Thomas, G., and Walker, P. (2018). Results of a survey of organizations preserving web content. https://osf.io/ht6ay/

Ferguson, C. L. (2017). Open educational resources and institutional repositories. Serials Review, 43(1), 34–38.

Gates, B. (1996, January 3). Content is King. https://web.archive.org/web/20010126005200/http://www.microsoft.com/billgates/columns/1996essay/essay960103.asp

Griffin, S. M. (2005). Funding for digital libraries research: Past and present. D-Lib Magazine, 11(7/8). https://www.dlib.org/dlib/july05/griffin/07griffin.html

Higgins, S. (2008). The DCC curation lifecycle model. International Journal of Digital Curation, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v3i1.48

Huang, C., Lee, J. S., and Palmer, C. L. (2020). DCC curation lifecycle model 2.0: Literature review and comparative analysis.

Hullavarad, S., O’Hare, R., and Roy, A. K. (2015). Enterprise content management solutions—Roadmap strategy and implementation challenges. International Journal of Information Management, 35(2), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.12.008

Internet Archive (n.d.). About the Internet Archive. https://archive.org/about/

Jenab, K., Noori, K., D. Weinsier, P., and Khoury, S. (2014). A dynamic model for hardware/software obsolescence. International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 31(5), 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-03-2013-0054

Lessig, L. (2008). Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Library of Congress. (2020–2021). Library of Congress Recommended Formats Statement. https://www.loc.gov/preservation/resources/rfs/TOC.html

Linde, P. (2006). Introduction to digital libraries—Memex of the future. In Proceedings ELPUB2006 Conference on Electronic Publishing, Sweden.

Lynch, L. (2020, March 5). Should You Switch from Moodle to LearnDash? https://www.learndash.com/should-you-switch-from-moodle-to-learndash/

Miller, R. and Homol, L. (2016). Building an online curriculum based on OERs: The library’s role. Journal of Library and Information Services in Distance Learning, 10(3–4), 349–359. doi:10.1080/1533290X.2016.1223957

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2011). Virtual worlds: Immersive online platforms for collaboration, creativity, and learning.

Petrov, P., Atanasova, T., and Kostadinov, G. (2019). Types, technologies and trends in e-learning. Information Technologies and Control, 3(5), 33–37. doi:10.7546/itc-2019-0015

Reed, J. B., and Jahre, B. (2019). Reviewing the current state of library support for open educational resources. Collection Management, 44(2–4), 232–243. doi:10.1080/01462679.2019.1588181

Reyna, J., Hanham, J., and Meier, P. (2017). A taxonomy of digital media types for learner-generated digital media assignments. E-learning and Digital Media, 14(6), 309–322.

Rydning, J., and Reinsel, D. (2021). Worldwide Global StorageSphere Forecast, 2021–2025: To save or not to save data, That is the question. https://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=US47509621

Salem, J. A. (2017). Open pathways to student success: Academic library partnerships for open educational resource and affordable course content creation and adoption. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.10.003

Simons, N., and Richardson, J. (2013). New Content in Digital Repositories: The Changing Research Landscape. Chandos Publishing.

Stafford, D. (2020). Promoting open educational resources: A beginner’s playbook. Pennsylvania Libraries: Research & Practice, 8(2), 103–114.

Venkitachalam, K., and Bosua, R. (2019). Perspectives on effective digital content management in organizations. Knowledge and Process Management, 26(3), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1600

Walz, A. R. (2015). Open and editable: Exploring library engagement in open educational resource adoption, adaptation and authoring. Virginia Libraries, 61(1), 25–31. http://doi.org/10.21061/valib.v61i1.1326